This series was produced in partnership with the Delaware Journalism Collaborative, a group of local news and community organizations, of which Delaware Call is a part, working to bridge divides statewide. Learn more at ljidelaware.org/collaborative.

[Editor’s Note: Throughout this series we provide links back to original source material and digitized newspaper archives. Unfortunately, many readers will not have access to these sites. However, we wanted to cite our sources, and also allow those with an interest to work back through documents to develop a deeper understanding of Wilmington history.]

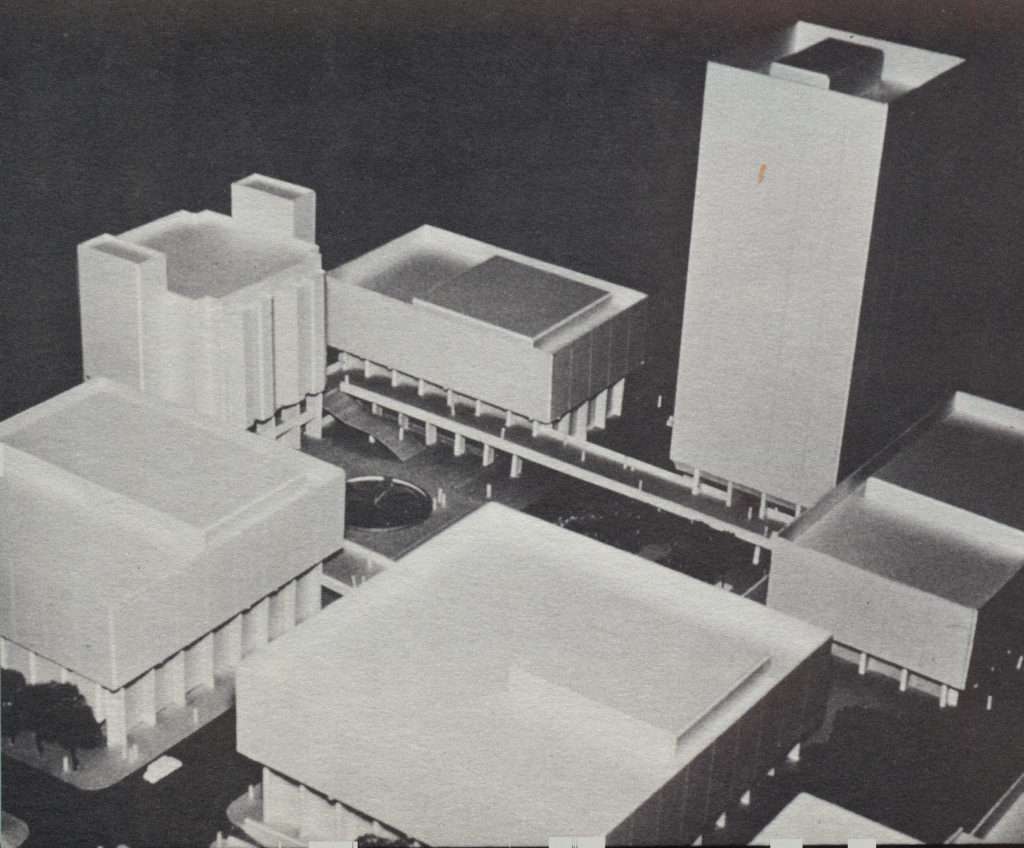

When the fate of the proposed civic center in downtown Wilmington was finally sealed as a massive urban planning failure in 1973, editor Norm Lockman, who for years was one of few critics of the civic center project at The News Journal, commemorated the occasion with an editorial titled, “Downtown Mall, Unrealistic Dream.”

“June 11, 1973,” he began. “Mark it on your calendar of blessed events. It was the day Mayor Tom Maloney mercifully delivered the coup de grace to one of the country’s utterly botched efforts at urban renewal: the proposed commercial complex of the Civic Center.”

In a scathing takedown that derided the civic center project as “hopelessly moribund,” an “embarrassment,” and a “grandiose scheme,” Lockman compared the whole affair to the short-lived DuPont product “Corfam,” a type of synthetic leather developed by DuPont that failed commercially after seven years; however, as Lockman noted, the civic center was undeserving of such a nickname because at least Corfam “got off the drawing boards.”

Lockman went on to suggest that the anniversary of the project’s failure be celebrated with “public burnings of Downtown Mall planning paraphernalia.”

“Next year, they could burn the cardboard model. The following year, burn a few of those prettily colored ‘time frame’ charts; the next year, the plans for the world’s only proposed freeway that leads into a garage,” he wrote.

Lockman slammed the project for its delays, Wilmington for being too unaccommodating, and local leaders for being unrealistic in their demands and expectations for the proposed civic center. He even called out former DuPont executive Henry B. du Pont, a major proponent of the civic center project who also served as president of the Greater Wilmington Development Council, for surrounding himself with yes-men who dared not contradict fanciful plans despite “all reliable indicators showing that theirs was a bad idea.”

“The general outlook was that the city had little to offer in the first place and was making little effort to go out of its way to take any risk to provide worthwhile economic inducements,” Lockman wrote. “So now the planners are scaling down their scheme . . . Ironically, about 18 months ago, a black group got together and proposed such a scaling down of the project . . . The group was viewed as a bunch of militant troublemakers by the elitist pro-commercial mall cadre.”

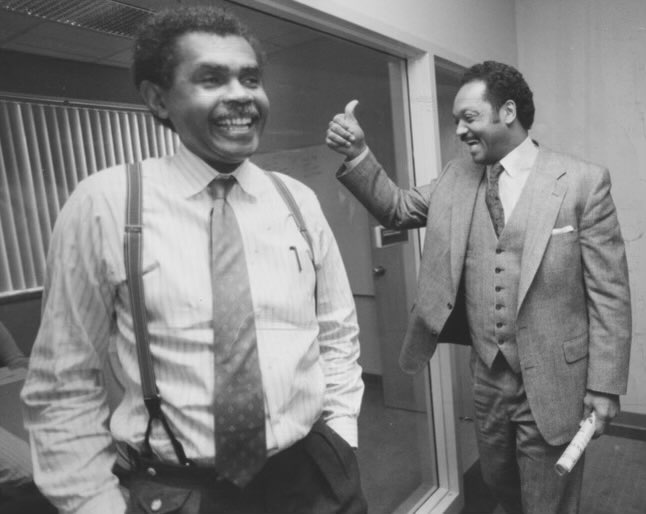

One of those “militant troublemakers,” Lockman wrote, had since been elected to Wilmington City Council. James Baker, who would become the longest-serving mayor of Wilmington from 2001 to 2013, “might be tempted to take a bag of salt to the [Greater Wilmington Development Council] to make the crow-eating chore a little less onerous.”

By now, however, Lockman wasn’t the only staffer at The News Journal openly criticizing the civic center project.

“The agony was ended yesterday for the long-suffering proponents of a regional shopping center in Wilmington’s Civic Center,” wrote veteran journalist Ralph Moyed. “And, for the fourth time in seven years, the authority will invite bids for developing the commercial section of the Civic Center.”

The News Journal editorial board called it “the end of what may have been an impossible dream.”

The “Missing Middle”

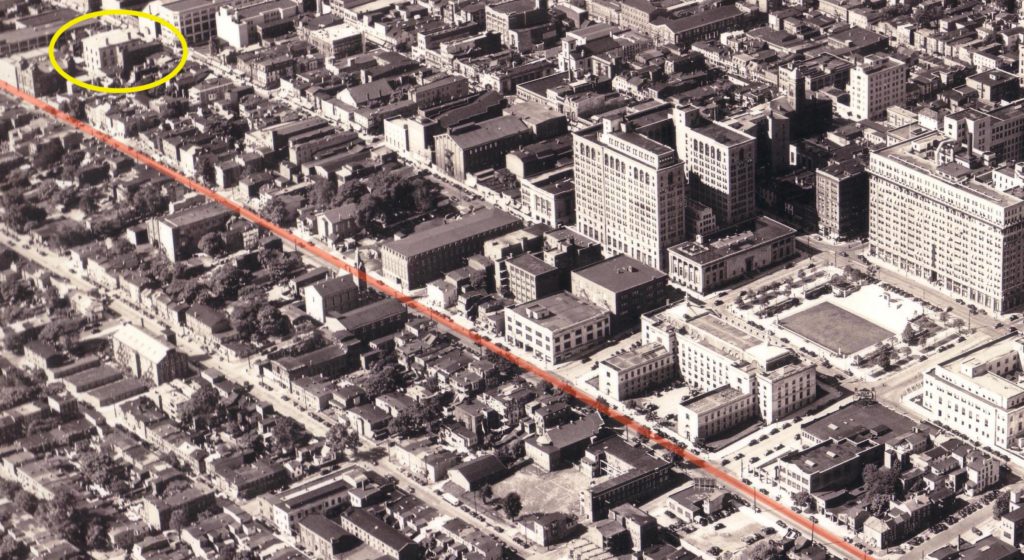

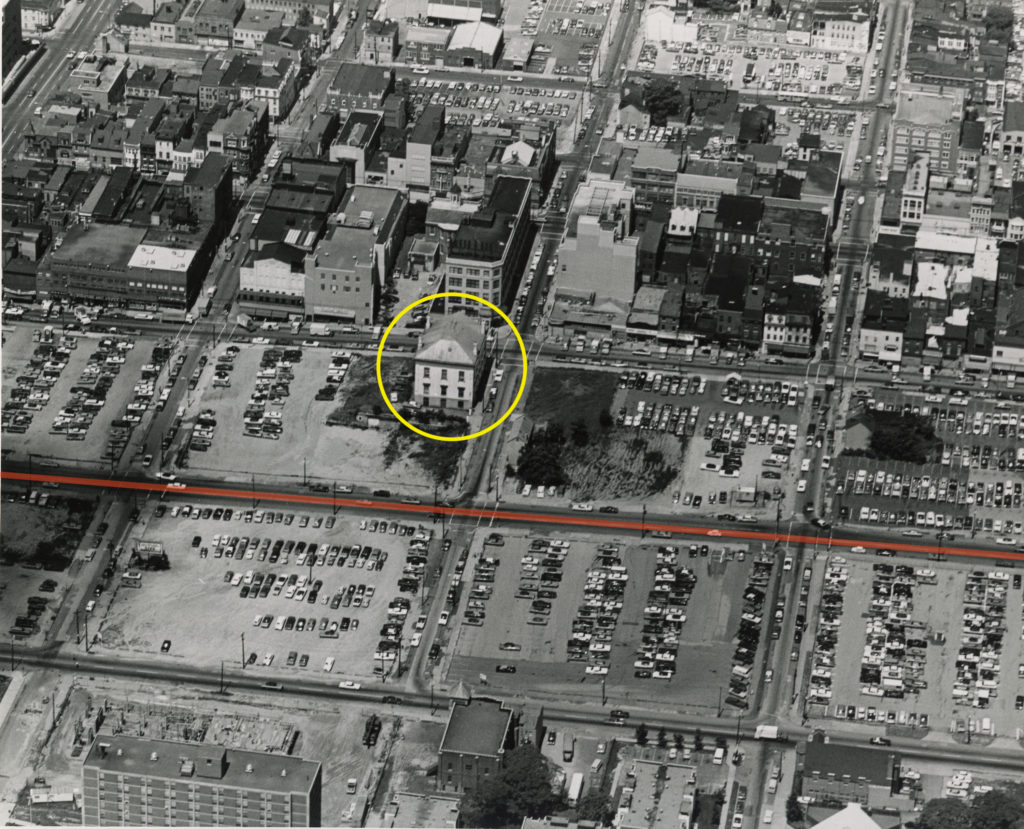

The damage done to Wilmington’s urban core was unmistakable by the mid-1970s. Thousands of residents had been displaced because of the construction of Interstate 95, slum-clearing around Poplar Street, and the demolition of French Street for a civic center that was never built. Along with the demise of the shipping industry along the Christina riverfront, downtown Wilmington was surrounded on three sides by areas that had been hollowed out of human activity. Far from saving Wilmington, actions by city leaders and the business elite only seemed to hasten its decline, with the city’s population falling from 95,000 in 1960 to just over 70,000 in 1980.

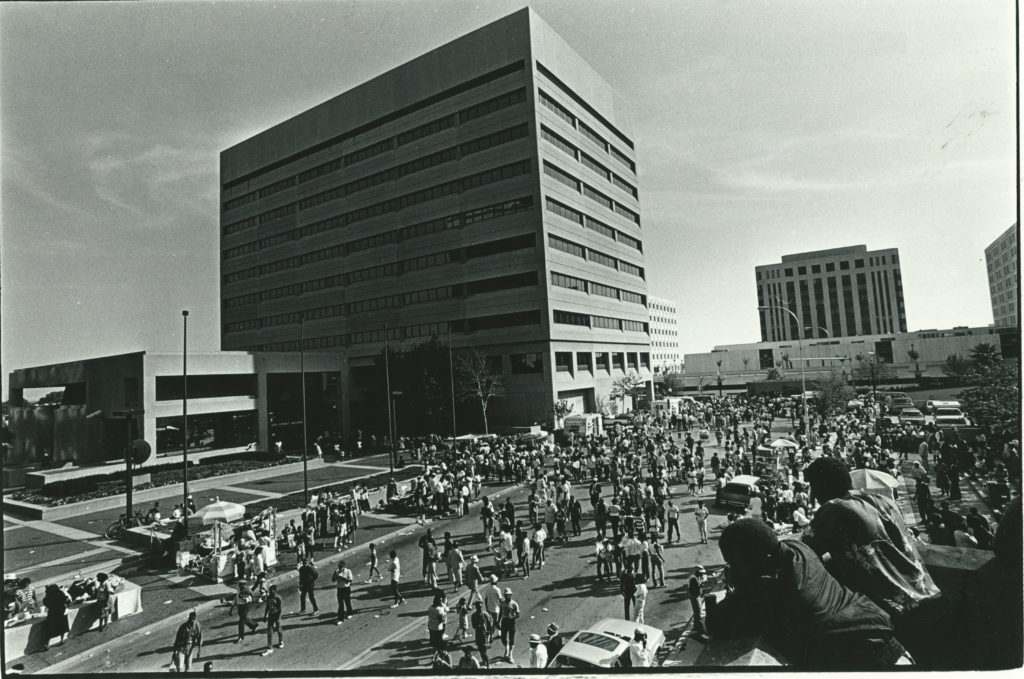

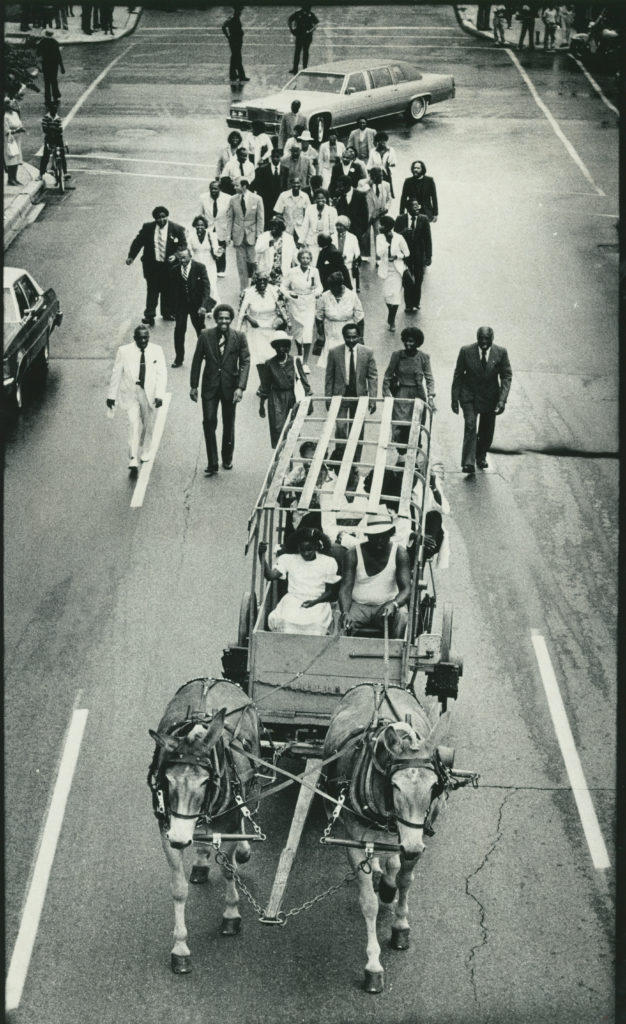

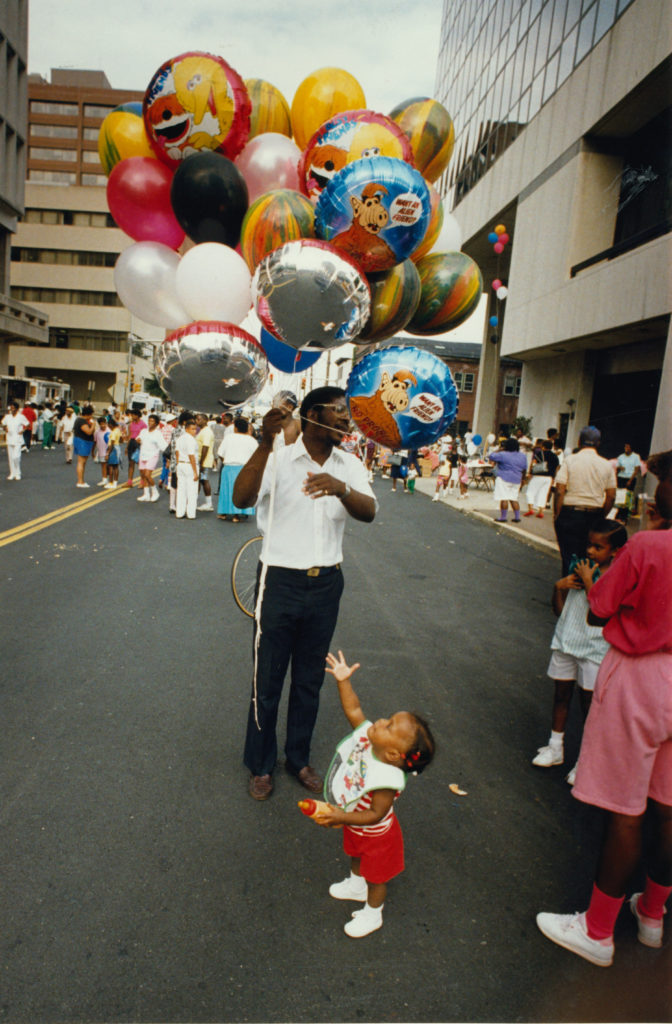

The area where Mother African Church once stood no longer bears any resemblance to the old neighborhood where the “Big” August Quarterly was held for more than 150 years. Along French Street, where Black churches and Black-owned businesses served the area’s Black community, there now stand state and federal government office buildings, a DoubleTree Hotel, the MetLife Building, several parking garages, and the New Castle County Courthouse. French Street below Fourth was eventually also demolished — the Chase Bank towers are there now — as were the blocks north of ninth, where MBNA built a complex of office buildings in the mid-1990s.

Much of that commercial development was prompted by the passage of the 1981 Financial Center Development Act, signed into law by Gov. Pete du Pont IV, which revised Delaware’s banking and tax codes in a desperate bid to attract out-of-state banks to establish subsidiaries in Wilmington. It worked so well that the area between King and Walnut streets finally resembles the collection of office towers that city and state leaders had long ago envisioned — just a few decades too late.

On Walnut Street, where the rear entrances of large office buildings are mostly reserved for deliveries and vehicles entering and exiting parking garages, the director of the Delaware State Housing Authority, Eugene Young, shakes his head at what happened to the neighborhood that he once called home.

“If you walk down Walnut Street, you get the sense the city turned its back on the east side,” he says. And it’s not just the symbolism of all those big office buildings literally facing away from the neighborhoods across the street, he explains. Commercial investment in downtown Wilmington over the decades has had almost no material impact on the east side. It remains one of the poorest sections of the city where three-quarters of residential units are rentals, he says. The neighborhood also lacks many amenities that the commercial hub around French Street once provided, meaning that residents need to travel farther to access goods and services.

The disparity between the east side and other neighborhoods in the city is bleak. Even as housing prices skyrocket and luxury apartment towers are erected downtown, boarded-up rowhomes are pervasive across the east side. Of the roughly 2,000 housing units east of Walnut Street, roughly 10% are vacant, according to Woodlawn Trustees President and CEO Rich Przywara. In partnership with the nonprofit Todmorden Foundation, Woodlawn owns 120 affordable housing units on the east side that it rents to low-income families based on guidelines set by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. Przywara hopes they will be adding dozens more in the coming years.

Woodlawn and Todmorden are the second-largest providers of affordable housing in Wilmington behind only the Wilmington Housing Authority, which manages nearly 2,000 housing units. Woodlawn also owns 455 affordable units in The Flats neighborhood on the west side between Fourth and Ninth streets. But even that’s not enough. The supply of affordable housing has not kept up with demand, and the waitlist to get into The Flats is currently two years.

“There’s just no way to build affordable housing entirely with private financing. We need government money,” says Przywara, adding that because Delaware is so small, only three affordable housing projects each year are approved for the federal government’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit. “It doesn’t have to be entirely funded by the government, but you can’t do this with a lot of debt. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is the number one way affordable housing gets built across America, and it’s based on population. We all compete for those awards.”

Just how bad is the housing shortage in Delaware? The state needs at least 21,000 additional rental units just to meet demand, according to Sean O’Neill, a policy scientist from the University of Delaware’s Institute for Public Administration.

“There is no silver bullet that will quickly, easily, and painlessly solve this problem,” said O’Neill. “The affordable housing problem is different in Wilmington, which is majority renters in rowhomes, apartments, and duplexes, than the housing problems facing northern New Castle County, which is mostly owner-occupied single-family detached housing built in the last 70 years. And these problems are different from those playing out in Sussex County, a tourist economy where housing prices along coastal areas have skyrocketed, locking many workers out of the market to rent or buy.”

At the current pace of housing construction, he adds, it is unlikely there will ever be enough workforce housing in eastern Sussex County.

Much of the dense urban housing that was demolished in Wilmington during the 1960s and 1970s was replaced outside the city in New Castle County almost entirely with single-family detached housing during a time when the county’s population grew by more than 91,000 residents. Black families initially faced stiff resistance from white neighbors when they attempted to move into the suburbs — in the Wilmington suburb of Collins Park in 1959, the Rayfield family faced protests and their house was firebombed, presumably by white neighbors — and “redlining” ensured that Black families were mostly unable to secure loans for properties in white neighborhoods until the late 1970s.

By the 1980s, Wilmington and many other cities across America had been so thoroughly gutted by highways and “urban renewal” projects that just about anybody who could afford it was trying to find a place to live in the suburbs, and as a result, in recent decades, the suburbs have grown much more diverse.

“The pattern of suburbanization is kind of an anomaly in human history,” says O’Neill. “Throughout human history, people have centered in cities, and it was only really that period from the 1950s to the 1990s when the suburbs were widely seen as a more desirable place to live” compared to cities, especially rustbelt cities, which people associated with blight and pollution, many largely unaware of how deeply cities like Wilmington contributed to their own demise.

Suburbanization played out in New Castle County in largely the same manner as it did across the country. People who relocated to the suburbs were typically moving to single-family detached housing, which became a widely-promoted standard of living in the United States that supposedly separated us from the rest of the world. It all sounded good at the time, but, as O’Neill notes, “eventually you run out of land.”

Because of restrictive zoning laws, the mixed-use urban housing that existed on French Street for over a hundred years is illegal to recreate in most communities, but we desperately need to bring it back, says Director Young, who refers to this type of housing stock as the “missing middle.”

With most new housing consisting of either luxury apartments or single-family detached housing, everything else in the middle — like rowhomes and mixed-use development typical of downtown areas — are missing from our communities, from the beaches to New Castle County.

“For the last 50 to 60 years, we have mostly built one type of housing in our state: About 60 percent of all properties built in our state are single-family detached homes. If you go to Kent and Sussex that number goes up to 80 percent,” says Young, adding that Delaware’s housing crisis lies, to some extent, in its inability to legalize the kinds of dense, walkable neighborhoods that once existed in so many American cities, including Wilmington. In the meantime, his office helps to coordinate state-level affordable housing grants to developers like Woodlawn.

But state and federal incentives are still not enough. Local governments, which largely supported the demolition of inner city neighborhoods decades ago, can help by revising their zoning ordinances so that the mixed-use communities that once existed can be rebuilt.

“We can do a lot more to incentivize more varieties of housing” to help meet demand in both cities and suburbs, says O’Neill. “If you zone something for multi-family development, like a multi-floor apartment building, then someone is going to build apartments there. In some sense, it just comes down to having the by-right zoning to build various types of housing. There are a lot of different ways you can make housing more affordable to folks, and to provide various types of housing other than single-family detached housing.”

Longtime Wilmington resident Harmon Carey agrees. When he looks at disinvestment in urban neighborhoods, part of the problem as he sees it are onerous restrictions on what can and can’t go on certain lots. When Carey was a child, it wasn’t unusual for a family to run a business out of the front of a house, especially small shops on corner properties while the family lived upstairs.

“There was a vibrant business climate on the east side, some of it owned by Blacks, some of it not owned by Blacks,” says Carey, 86, whose family moved to the east side when he was just a young child. Now retired, Carey still owns property on the east side, including the first Black-owned radio station in Delaware, WHGE 95.3 FM, located on Pine Street. (Carey was pictured in the first part of this story at the unveiling of a portrait of Mother African founder Peter Spencer.)

“People didn’t want to open a business in the middle of the block — you opened a business on the corner,” Carey recalls. But that’s largely gone now as most of the east side is zoned as single-family rowhomes with very few areas zoned for small businesses. “Instead of the city trying to maintain these spaces for businesses, they allowed people to develop those corners into rentals. It helps on the one hand by providing housing, but on the other hand it diminishes amenities for the community.”

Such are the challenges facing Wilmington and communities across Delaware. After gutting urban neighborhoods for decades, the supply of housing has not kept pace with demand, and where housing does exist, especially affordable housing, there are typically fewer amenities than what once existed in downtown neighborhoods that were demolished. Cities and counties are mostly zoned to keep residential and commercial neighborhoods separate, but people haven’t always lived that way. Cities have historically been vibrant places where people live around the places where they shop, eat, and worship.

So what should state and local governments do? If urban planning over the past 50 years has largely centered on the interests of the corporate elite, perhaps the next 50 years should put the interests of people, not corporations, at the center of the discussion. And zoning plays a big role in that transformation.

What does this mean?

It means rebuilding the neighborhoods that we lost. Some cities have chosen to remove highways that cut through neighborhoods and devastated communities. Here in Delaware, there have been talks to cap I-95 in Wilmington, similar to what Pennsylvania is doing in Philadelphia near Penn’s Landing. But what about downtown Wilmington? What if we were as bold as those city and state leaders who carved a trench through Wilmington to create I-95, and demolished Fresh Street for a civic center that was never built?

If cities can remove highways, why can’t we also remove office buildings? After all, do we really need half-empty office buildings taking up space in a historic neighborhood when the city-wide office vacancy rate is almost 28%? Wilmington is beginning to see office-to-apartment conversions, which is fine, but what if we also tore some office buildings down and rebuilt the city similar to what it once was? What if we reversed the decades-long privatization of public spaces in Wilmington that has left the city unrecognizable compared to what existed only 60 years ago?

It’s not a perfect solution, and rebuilding Wilmington may be difficult for some to imagine. But it already happened, and not that long ago — that’s why the city looks the way it does today.

Acknowledgements

The Delaware Call would like to thank everyone who supported us in putting this series together:

The Delaware Journalism Collaborative for providing funding to research and write this series, including Darel LaPrade and Allison Levine.

Delaware Historical Society Executive Director Ivan Henderson, Chief Curator Leigh Rifenburg, and Outreach Coordinator Kobe Baker for their assistance throughout the course of this project, as well as organization’s librarians and archivists who maintain the digital collections that were used extensively while researching and writing this series.

Longtime residents of the east side, Harmon Carey, Kamau Ngom and Judith Roane, for sharing their recollections, Chioma Amaka and Crystal Hayman-Wilson for helping connect us with community contacts, the Peter Spencer Heritage Hallway Players from the Peter Spencer Family Life Foundation, and the Mother AUFCMP Church.

The staff, archivists, and librarians at Hagley Library and Museum.

Eugene R. Young, Jr., Director of the Delaware State Housing Authority

Steven Leech, for his wonderful book “Boysie’s Horn” on the history of Jazz in Wilmington

Historians Professor Dael Norwood and Syl Woolford for their advice and inspiration.

Thanks also to Policy Scientist Sean O’Neill of the University of Delaware, Rich Przywara, President and CEO of Woodlawn Trustees, Brian DiSabatino, President and CEO of EDiS Company, and Brandy Nauman, Director of Community Development for Sussex County, who collectively provided far more insight on land use and affordable housing than could be included in this series.

State Sen. S. Elizabeth Lockman for providing photographs of her father, Norman Lockman.

Kim Reis at USA Today for donating historical images for use in this series.

Last but not least, thanks to James Johnson for loaning us his extra copy of “The Company State”.