This series was produced in partnership with the Delaware Journalism Collaborative, a group of local news and community organizations, of which Delaware Call is a part, working to bridge divides statewide. Learn more at ljidelaware.org/collaborative.

[Editor’s Note: Throughout this series we provide links back to original source material and digitized newspaper archives. Unfortunately, many readers will not have access to these sites. However, we wanted to cite our sources, and also allow those with an interest to work back through documents to develop a deeper understanding of Wilmington history.]

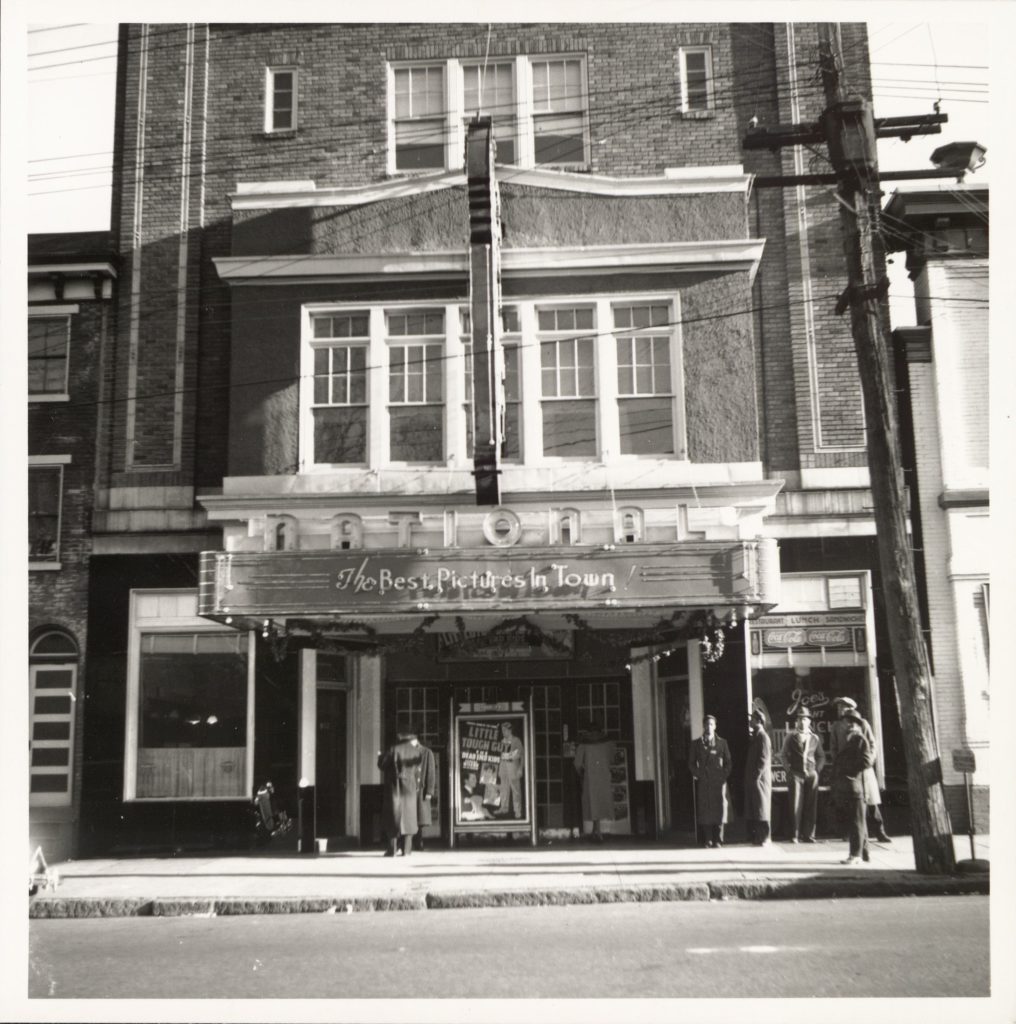

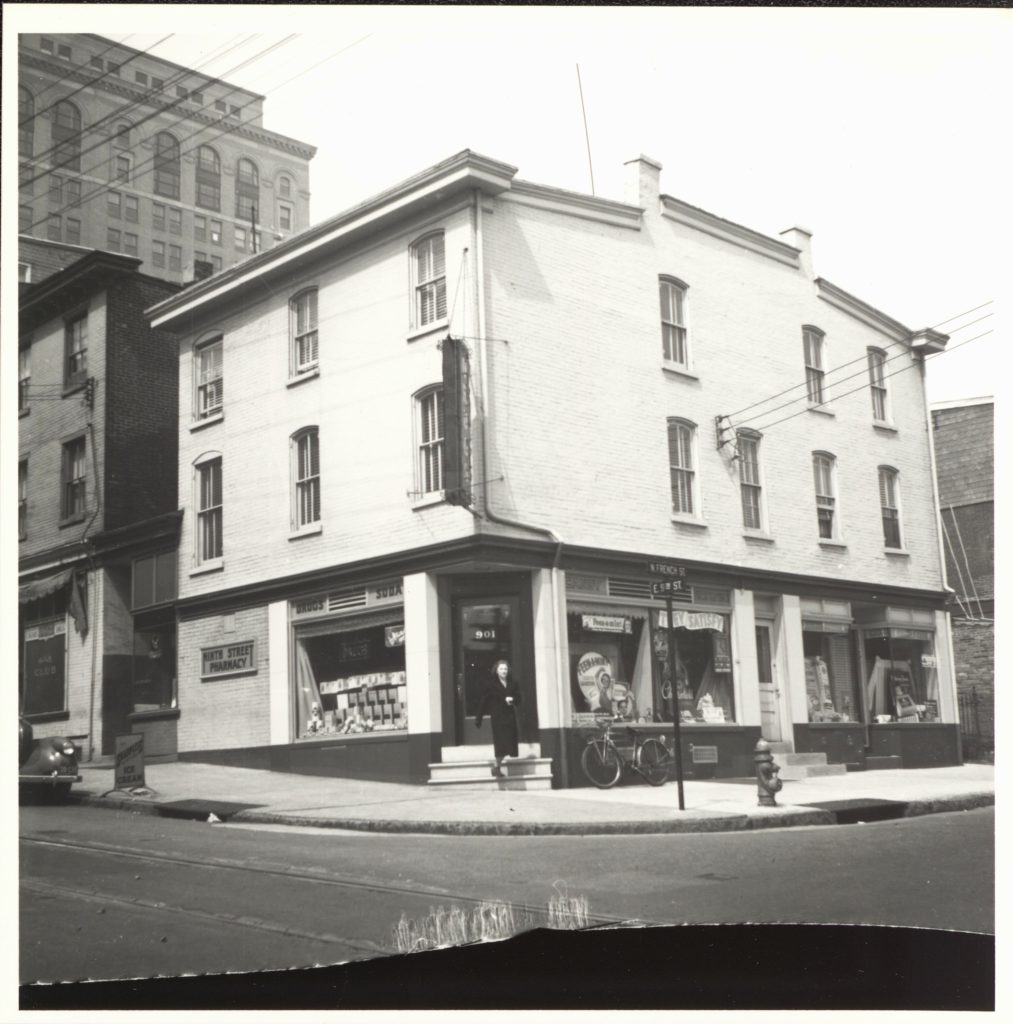

As a border state, Delaware isn’t northern or southern so much as northern and southern. During the Jim Crow era, Delaware’s Black citizens enjoyed more civil liberties than they would have in deep southern states, but racial segregation was pervasive, persistent, and by design. As such, most of Wilmington’s Black residents lived in the Eastside, Southbridge, and Riverside neighborhoods, and the commercial and cultural center of Black Wilmington was located around French Street, where businesses, churches, jazz clubs, restaurants, community organizations and more served Black residents who would have been denied services elsewhere.

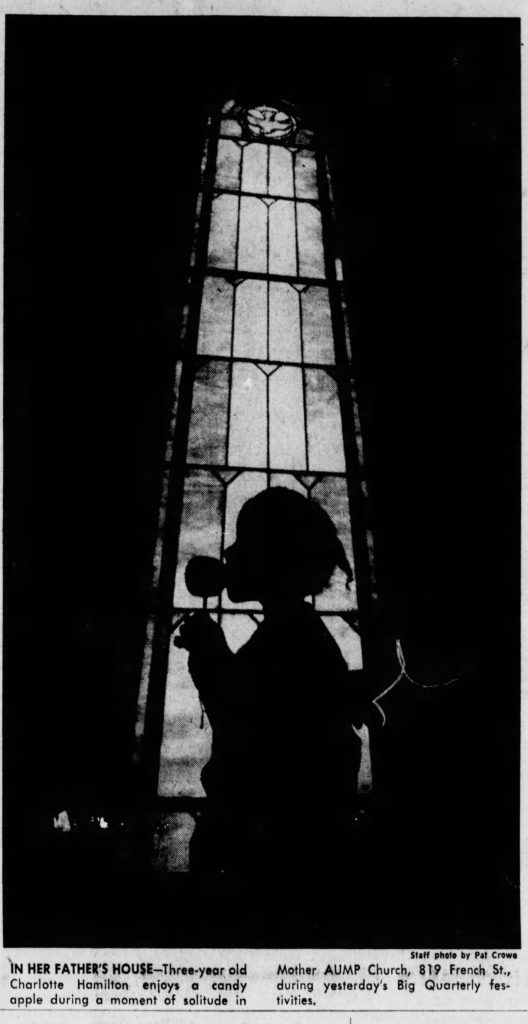

French Street was also the site of the annual “Big” August Quarterly celebration hosted by Mother African Church on French Street. According to longtime resident Judith Roane, who was born in Wilmington in 1940 and has attended nearly every Big Quarterly held during her lifetime, what made the east side so special growing up was that almost everything her family needed could be found on French Street and the surrounding business hub in Black Wilmington.

“That was our little Camelot,” she said. “We had everything!”

Despite segregation, the neighborhood thrived because of deep and meaningful community connections, with some families tracing their roots on the east side back five or six generations, putting their ancestors within the same lifetime as Mother African founder Peter Spencer. For Roane and many thousands of others, French Street was the center of the world.

However, from the perspective of Delaware’s government and business leaders, there was less to celebrate. Wilmington’s east side had long been a problem in need of a solution. Every year when the Big Quarterly arrived on French Street, the city’s white residents reacted to the influx of Black travelers with a mixture of anxiety and curiosity, according to contemporary newspaper reports examined in the first part of this series. Nevertheless, the festival continued uninterrupted year after year as city and state leaders were apparently content with segregating Big Quarterly festivities to Black neighborhoods.

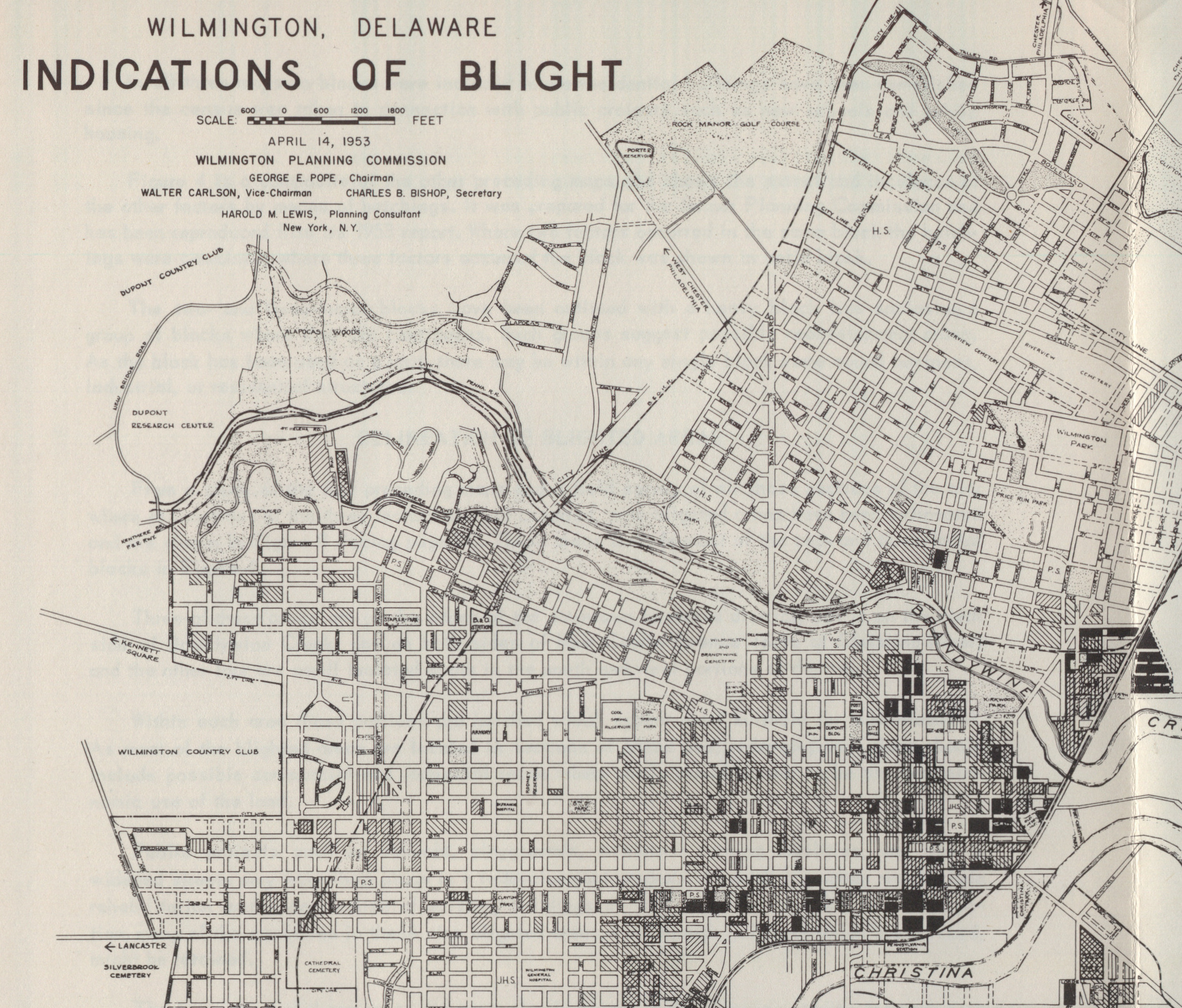

That all began to change during the 1950s when Black neighborhoods across America came under siege as cities embarked on massive urban redevelopment projects, or “slum clearing,” thanks to provisions in the Housing Act of 1949 that provided funds for federally-approved projects. The law, signed by Harry Truman, also required cities to demolish or renovate one blighted “slum dwelling unit” for every new unit built using federal funds. The Eisenhower Administration doubled-down on federally-backed slum clearing with the Housing Act of 1954. For a small city like Wilmington, this opened the door for large-scale urban redevelopment projects that otherwise would have been beyond the capabilities of local government.

“We are all well aware of the fact that blighted areas contribute largely to municipal problems,” Wilmington Mayor August F. Waltz said in remarks praising the newly enacted housing act published in the morning newspaper on Dec. 31, 1954. “A realistic approach [to urban revitalization in Wilmington] has two parts, one — the elimination of the existing slums, and two — the prevention of fast growing blight which is affecting our better areas.”

Waltz was speaking, of course, about Wilmington’s east side, where he and four subsequent mayoral administrations would spend the next 20 years promulgating urban renewal projects with the backing of major corporations like DuPont.

Ideas had been floating around for years in Wilmington to build some kind of “civic center” downtown, but it was only after the police disturbances at the 1961 Big Quarterly that city leaders renewed these calls with greater urgency, and those conceptual ideas very quickly became reality.

Just a few weeks after the Big Quarterly in October 1961, Mayor John E. Babiarz traveled to Washington D.C. for a meeting with the head of the General Services Administration, hoping to secure a commitment from the federal government to build an office building in Wilmington. To be in compliance with federal guidelines that the building be located in an urban renewal zone, city officials initially suggested a site several blocks away from downtown along Poplar Street, where another redevelopment project was already underway.

However, according to a report in Wilmington’s morning newspaper on Oct. 4, 1961, in preparation for the mayor’s trip, the architectural firm Whiteside, Moeckel and Carbonell was contracted to develop plans for a “civic center” closer to downtown that would include “a mall, new city and state office buildings, parking facilities and possibly a civic auditorium.”

It must have seemed like a longshot, but the next day Mayor Babiarz returned from Washington with exciting news: If the city council approved a new civic center renewal zone closer to downtown by Nov. 1, then the GSA would locate their new office building in the project area.

With that announcement, Delaware’s political and business leaders had the green light to envision a new downtown for Wilmington.

“Civic Center Ahead”

The proposed federal building became the lynch pin of the entire civic center project around French Street. In pursuing a deal with the GSA to erect an office building downtown, city leaders hoped that municipal development would trigger private investment in the surrounding blocks and reverse a decades-long commercial decline in the heart of Delaware’s largest city. The revitalization project became known as Project C.

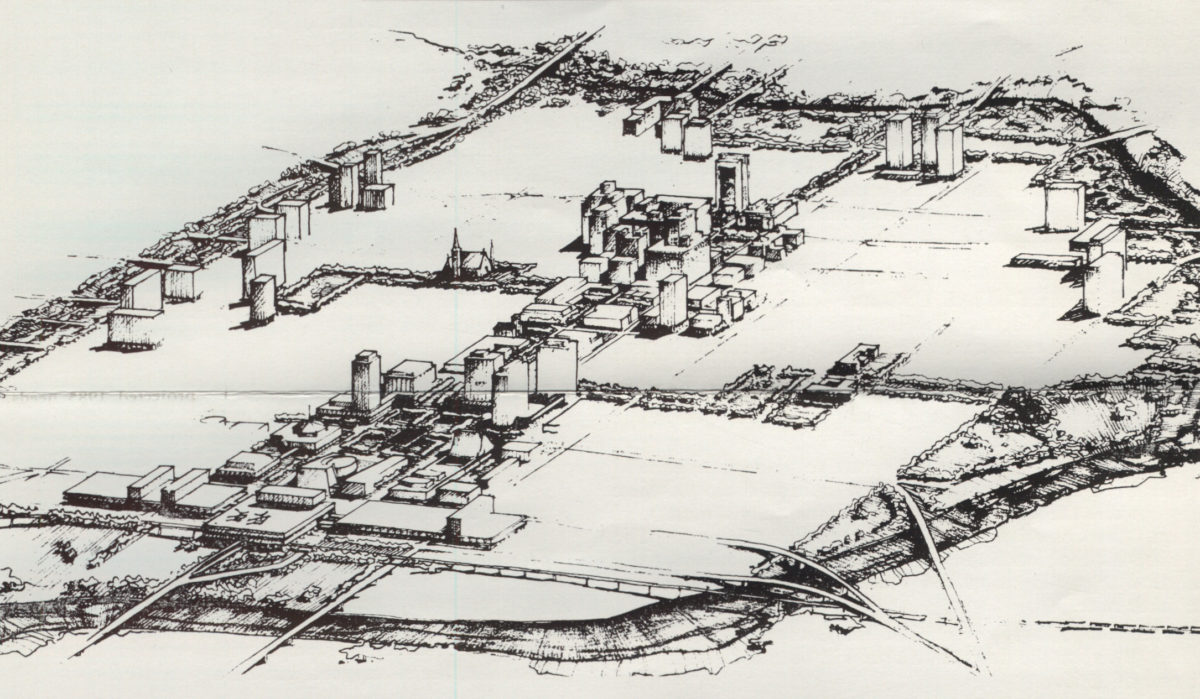

As part of the ambitious revitalization plan, initial renderings by architect William G. Moeckel envisioned 12 mixed-use blocks on the east side transformed into modern office buildings with a tree-lined plaza connecting the civic center to businesses on King and Market streets, according to renderings published on the front page of the morning newspaper. Most of the project area was located around Seventh Street between Walnut and Lombard, which meant that revitalization would largely spare many of the businesses, churches, and other organizations that formed the commercial core of Black Wilmington on the east side of downtown.

Over the following weeks, however, plans for the civic center project changed significantly. On Oct. 27, without much if any public input, Wilmington City Council voted in favor of designating 10 blocks on either side of French Street between Fourth and Ninth as the official urban renewal zone for the civic center project, thereby pushing the redevelopment area directly into the heart of Wilmington’s Black downtown.

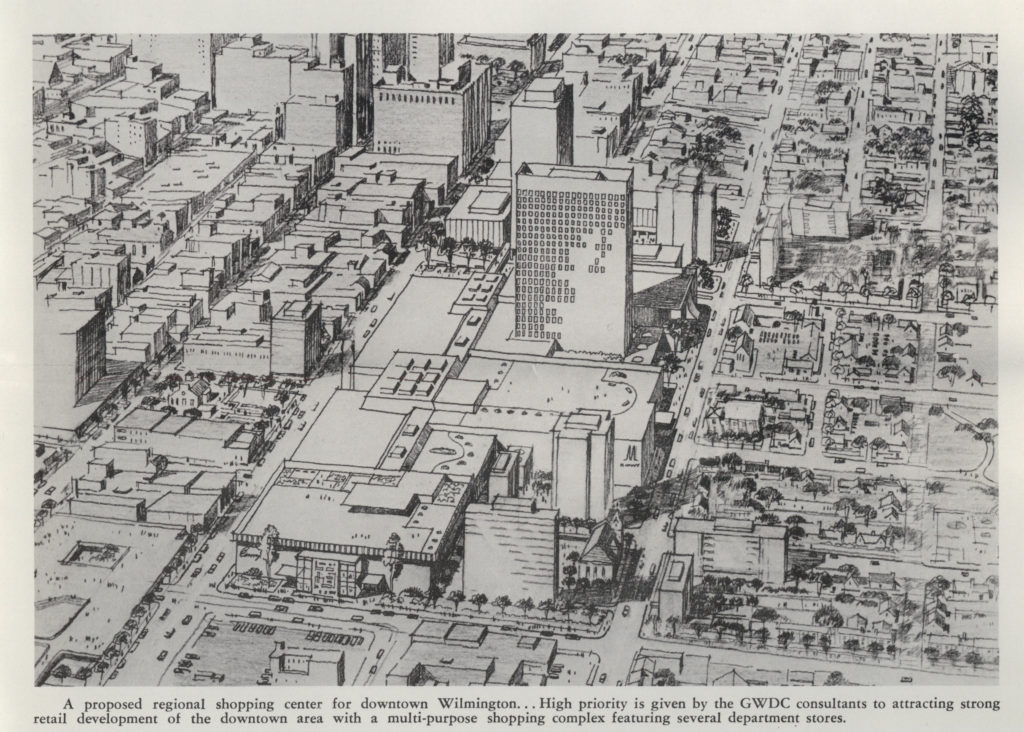

Not long after the council vote, new renderings of the civic center project appeared on the front pages of Wilmington’s daily newspapers. The new plan, prepared by the nonprofit Greater Wilmington Development Council (GWDC), called for “flexibility” locating a new civic center design closer to downtown. The plan envisioned transforming twelve city blocks into a complex of government office buildings with open lawns and tree-lined sidewalks, a 3,000-seat auditorium, parking garages, and a skating rink.

The Wilmington of old would soon become a memory, replaced by the kind of gleaming modern office buildings that — as illustrated in designs published by the GWDC — could have doubled as some futuristic urban utopia in a comic book. Wilmington’s daily newspapers hailed the project uncritically as the “Key to City’s Future,” according to the headline of Wilmington’s morning newspaper on Nov. 14. That evening, the front page proclaimed: “This Way, Wilmington — Civic Center Ahead.”

“We cannot afford to miss another opportunity to build a foundation for a better Wilmington,” stated the GWDC in official remarks published on the front pages of Wilmington’s daily newspapers. “Reality is rarely greater than the dream that creates it. For this reason, the development council wants to stimulate imaginative, yet hard-headed, thought toward developing a plan and determining the location for a civic center.”

When approved by City Council, Project C became the second active urban renewal project on Wilmington’s east side, the other being along Poplar Street — known as Project A — a 22-block site located between Fifth and Ninth streets east of Walnut that was approved for redevelopment in 1953 by the Wilmington Housing Administration and which required the demolition of more than 600 structures. Demolition for the Poplar redevelopment project began in 1960, just a few months after demolition started on more than 360 homes on the west side to make way for Interstate 95. More than 100 more structures would eventually be demolished within the civic center urban renewal zone.

“Most people in the neighborhood did not want the civic center project to move forward because we did not want to lose what we had,” recalls Judith Roane. “We knew that we stood to lose everything. Schools. Businesses. Homes. So there was a lot of contention. A lot of people did not want it.”

The ostensible purpose of urban renewal zones was to renovate or replace blighted structures. However, the problem with urban renewal around French Street is that most of the structures were already in good condition. According to a map of assessed land values conducted by the Wilmington Planning Commission, only two of the ten blocks in the urban renewal area experienced declines in property values from 1938 to 1954 while every other block increased, some by more than 50 percent. The worst declines were further east around Poplar and Lombard streets and to the southwest along Front Street. And although other documents by the planning commission now held at Hagley Museum and Library show moderate levels of blight around French Street, it certainly wasn’t exceptional when compared to predominantly white neighborhoods to the west.

In other words, the commercial core of Black Wilmington around French Street was in fair shape, but that didn’t stop the bulldozers.

Wilmington’s slum-clearing business

Home of the DuPont Corporation, Wilmington had always been a company town. Through a complex network of influence, the du Pont family — and therefore DuPont the corporation — controlled two of Delaware’s four major banks, several law firms, both daily newspapers, and multiple public charities. As such, when the city started getting serious about ambitious urban redevelopment projects in the early 1960s, DuPont had already formed a “grassroots” nonprofit urban development organization — the Greater Wilmington Development Council — to influence public policy planning to the benefit of commercial interests.

From the start, the GWDC was “in no way representative of the city’s population,” according to “The Company State,” a special report on DuPont in Delaware written by a team of researchers led by political activist and future presidential candidate Ralph Nader in 1969. On paper, the GWDC was a nonpartisan, nonprofit corporation that acted as “the urban development agent for the business elite” in Wilmington, according to Nader’s report. The nonprofit’s leadership was almost entirely controlled by du Pont family members and employees of the DuPont Corporation with the set purpose of shaping urban renewal in Wilmington to benefit Delaware’s powerful corporate interests. As Irenee du Pont, Jr. reportedly said, GWDC was “the businessman’s approach to community affairs.”

The council’s internal records are far more laudatory, of course. According to an institutional history written by Wilmington Planning Director Peter A. Larson, now held at Hagley Museum and Library, between 1960 and 1985 the GWDC was “a presence at the leading edge of physical and social changes taking place within the city of Wilmington and its environs,” and “made significant contributions to the economic, social, and cultural well-being of Greater Wilmington.”

The council was formed in 1959 after a meeting of business executives organized by Mayor Eugene Lammot — a du Pont relative who served as mayor from 1957 to 1960 — over concerns about Wilmington’s decline.

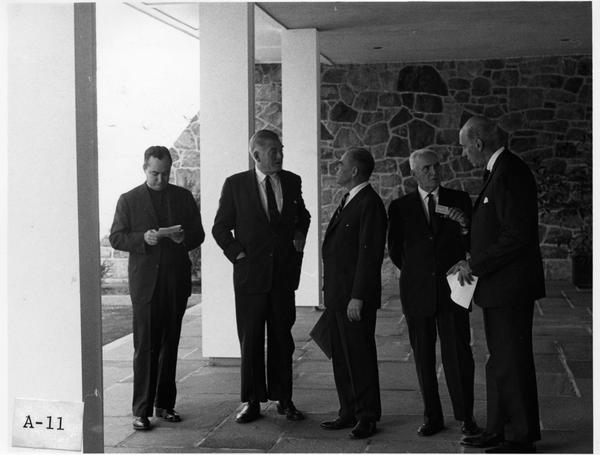

Although the DuPont corporation strongly objected to the Nader report’s criticism as “completely one-sided,” the GWDC’s own institutional history proudly recognizes DuPont’s influence on the organization’s leadership, which included longtime DuPont Vice President Henry B. du Pont, who served as GWDC board president from 1963 to 1968, and his successor Irenee du Pont Jr., who served from 1968 to 1975 and again from 1982 to 1985. According to the institutional history, H.B. was a “working chairman” who kept an office at GWDC in addition to one at DuPont, and over his time as chairman developed a “solid personal relationship” with Mayor Babiarz.

“As one businessman remarked,” according to the Nader report, “H. B. was GWDC.”

Although they disagree in some respects, the Nader report and the GWDC institutional history make one thing clear: With the full support of the du Pont family and DuPont Corporation, GWDC shaped Wilmington to reflect the desires of the business elite.

“GWDC is so involved in the traditional work of urban government that many local public decisions are not made democratically through the municipality, but undemocratically through GWDC, or some mixture of both,” according to the Nader report. “Indeed, practically every new urban concept in Wilmington originated in GWDC and was then carried out by public planners.”

The civic center project is a good example of this corporate nonprofit-to-government pipeline for redevelopment projects. To help sway public opinion in favor of a downtown civic center, the GWDC produced a short film called “Which Way Wilmington?” that over the next several years was screened during hundreds of community meetings. According to the GWDC institutional history held at Hagley, community meetings screening the film were regularly held during lunch hour in downtown Wilmington and attracted “many downtown businessmen and professionals.”

For the average person whose primary source of information were reports in the daily newspapers, which had been owned by du Pont family members since 1911, there was precious little criticism of the civic center project for many years. In 1962, as the civic center project struggled to get off the ground, the evening newspaper ran a three–part series authored by the GWDC titled “Focus on Planning” that sought to justify its redevelopment projects in Wilmington. When the civic center project nearly fell through in 1964, the evening newspaper — which was controlled by the du Pont family — ran an editorial titled, “By All Means Keep Fighting.”

Among the confluence of all these special interests, the GWDC suddenly became the most influential public planning organization in Delaware, complete with an office at Market and Ninth streets that opened shortly after the release of the civic center proposal in November 1961.

Despite protests and pleas from residents, businesses, and church leaders to reconsider the proposed location of the civic center project, the city of Wilmington — influenced by DuPont and du Ponts through the nonprofit GWDC — moved forward with the redevelopment project along French Street.

“And the Walls Came Tumbling Down”

One can imagine how promising the civic center project must have looked to city leaders back in 1961. With such generous support from the federal government, for both the renewal project itself as well as the commitment to include an office building in the project area, the civic center probably looked like a done deal — but not for long.

Obstacles appeared almost immediately. Prior to approving plans for the civic center, Wilmington had entered into an agreement to build a $7 million parking garage and farmers market on Seventh Street between French and Walnut. Wilmington now had to renegotiate the terms of that agreement, likely at a loss. Meanwhile the King Street Merchant Association called the city’s civic center plans “pie in the sky” in January 1962 and said the project “won’t get off the ground.”

Between 1961 and 1963, Wilmington failed to develop coherent redevelopment plans for the proposed civic center project, and as such the city slogged through the federal approval process. In a near-fatal blow to the project in 1963, the General Services Administration decided to change the location of the proposed federal building. After years of delays, the GSA decided to locate its new office building at 12th and Market streets. Wilmington’s morning newspaper called the decision “a serious setback to Wilmington’s Civic Center project.”

“I hate to hear it,” Mayor Babiarz responded to the news. “We’ll have to review the plans.”

Delaware Gov. Elbert N. Carvel was more direct. “I may write the President,” he said, and the next year, he did. As the morning newspaper reported at the time, “GSA fight will go to LBJ.”

Meanwhile, the GWDC expressed dismay at the decision.

“It’s unfortunate that the federal government has moved unilaterally on the federal office building and ignored the wishes of the local community,” said DuPont research chemist Russell W. Peterson, who was also chair of the GWDC Planning Committee. Peterson would go on to serve as governor of Delaware from 1969 to 1973. “I hope today’s decision is not irrevocable.”

Despite setbacks, Wilmington soldiered on. In 1964, the city council formally approved detailed plans for the civic center that would open the door to more federal funding. Gov. Carvel even mentioned the project in his 1964 state of the state address, urging legislators to fund the state office building that was to be located within the civic center redevelopment zone, but all to no avail. By March 1966, the front page of the evening newspaper reported that the civic center project was “moving snail-like.”

“The Civic Center is progressing, but so slowly that it appears to be standing still,” wrote reporter Jerry Sapienza. “Greatest hope, and hence the greatest disappointment so far, has been in the federal office building to be erected by the General Services Administration.”

Demolition finally began in 1967, which the GWDC celebrated in its annual report with an image of a bulldozer turning a building into rubble next to the headline: “This has been an exciting year!”

Meanwhile, plans for the civic center continued to change — all on paper, at least. In October 1967, the consulting firm Wise and Gladstone released a study recommending that plans for the civic center project be reconfigured to accommodate a regional shopping mall, claiming that “Wilmington’s core can realistically become a complete and vital downtown for a large, multi-state market.”

Despite having no clear plan for what would become of French Street, demolition of the east side continued nonetheless. Just three weeks before the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and subsequent riots — which damaged 21 structures in downtown Wilmington — notice ran in the morning newspaper on March 12, 1968 that the city was seeking bids for the demolition of 107 structures on the east side.

Following the riots and National Guard occupation of Wilmington in 1968 and 1969, the success of any downtown redevelopment project suddenly hinged on the construction of an interstate spur that would have cut across downtown Wilmington along Front Street and terminated in a massive 5,000-space parking garage — the only example of such an urban planning design in the country, according to newspaper reports — thereby allowing people to drive from the suburbs directly into the Wilmington mall without ever having to step foot outside.

In the midst of the demolition of French Street, between 1967 and 1969, the Big Quarterly celebration dwindled into a shadow of what it once was. In 1967 the Quarterly was rained out, and in 1968 the newspaper proclaimed the Big Quarterly existed “in name only,” in part because so much of the neighborhood had been demolished and much of downtown was, in effect, under military occupation.

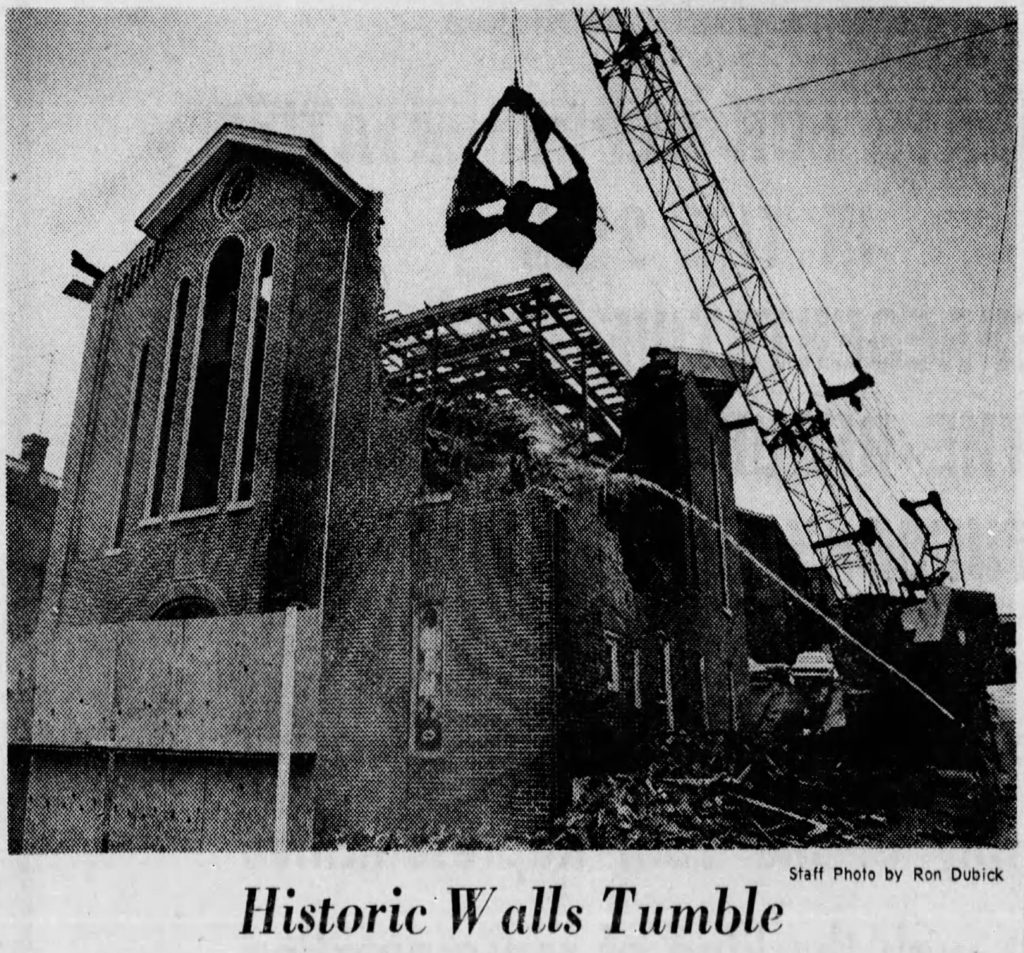

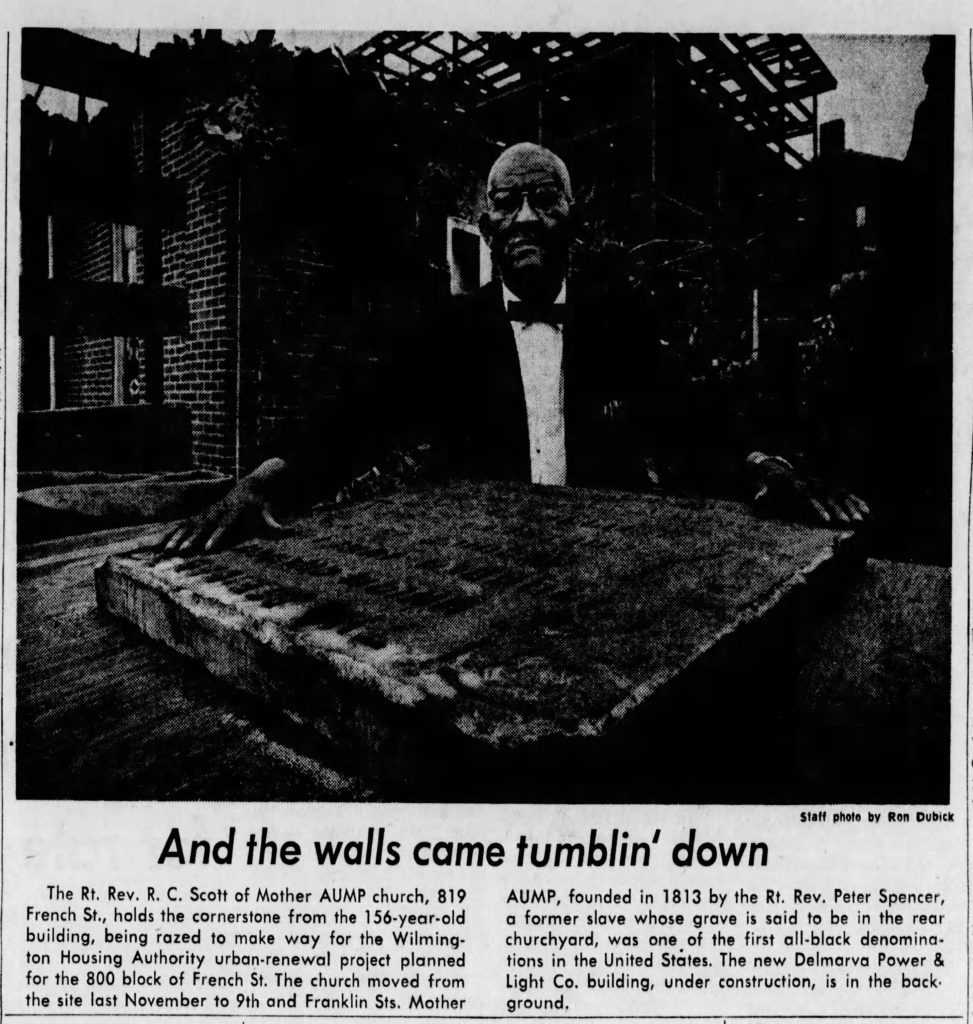

The final Big Quarterly on French Street was celebrated in 1969 by fewer than 200 people. The leader of Mother African Church, Rev. R.C. Scott, was pictured in the June 5, 1970 issue of the morning newspaper holding the cornerstone of the church as demolition crews went to work behind him. That same issue also contains an image of the church with its brick walls crumbling like Jericho as a crane lowered steel jaws to rip apart the wooden floors and knock the building down. The body of Peter Spencer, founder of Mother African Church, and that of his wife and several other parishioners, were disinterred and relocated to the plaza downtown that bears his name. The congregation moved to North Franklin Street on the west side, where the church remains to this day.

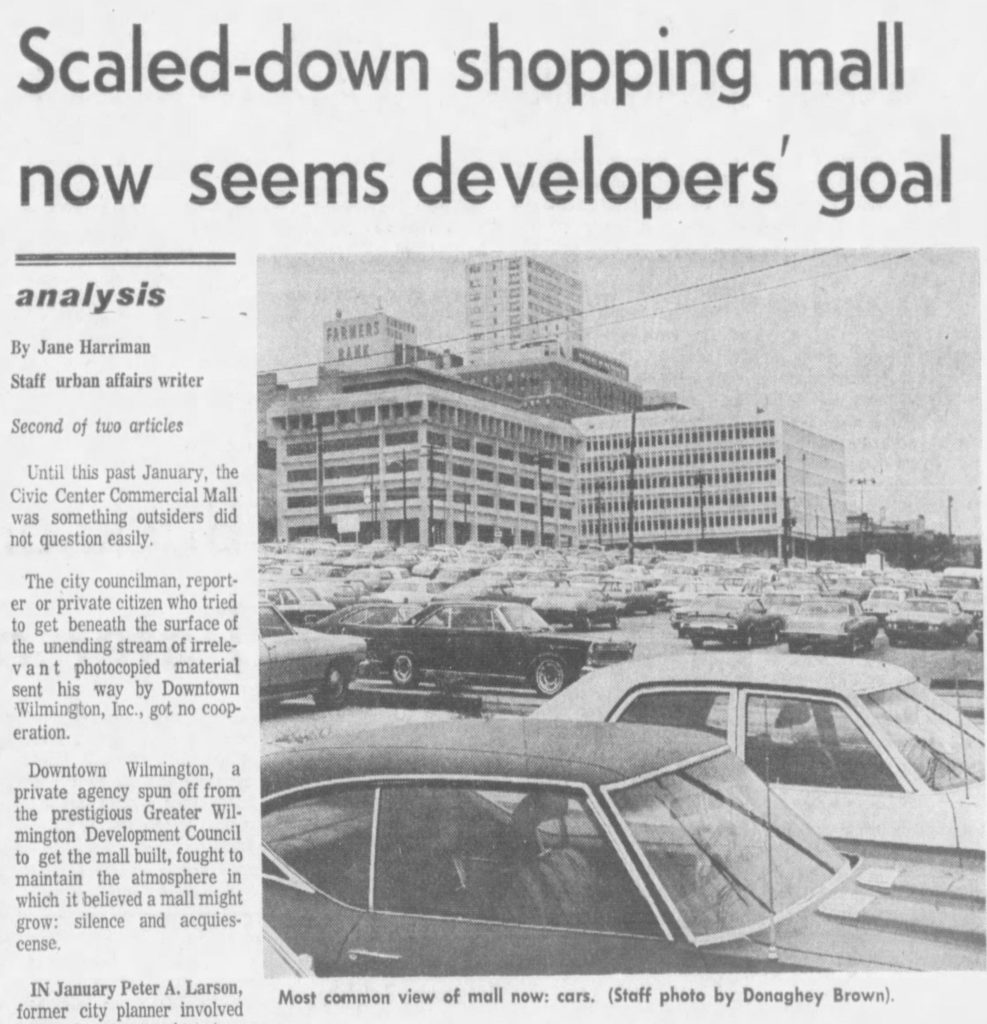

By 1972, the east side lay in ruins and the civic center project was hopelessly moribund. The commercial and government organizations that may have relocated to an urban renewal zone in downtown Wilmington in 1961 were no longer interested. Even DuPont’s own newspapers were openly questioning the project. In 1972, a staff photo by Donoghey Brown showed multiple blocks of parking lots where buildings once stood.

“Most common view of the mall now,” the caption read, “cars.”

To make room for a civic center that was never built, and then a shopping mall that was never built, city and local leaders ordered the demolition of a dozen city blocks around French Street, where the heart of Black Wilmington once stood. But it would be decades before the city’s plans would actually come to fruition. In the meantime, over the devastation of the east side, they built parking lots.

“To lose all that,” says Judith Roane “was like having your heart cut out.”

The final installment of the series, titled “Wilmington’s Biggest Boondoggle”, will cover lessons learned and 21st century housing and land use policy. It will be published Thursday, September 7