This series was produced in partnership with the Delaware Journalism Collaborative, a group of local news and community organizations, of which Delaware Call is a part, working to bridge divides statewide. Learn more at ljidelaware.org/collaborative.

[Editor’s Note: Throughout this series we provide links back to original source material and digitized newspaper archives. Unfortunately, many readers will not have access to these sites. However, we wanted to cite our sources, and also allow those with an interest to work back through documents to develop a deeper understanding of Wilmington history.]

Wilmington hasn’t always looked like this.

All cities change, of course. But in Wilmington, change seemed to happen not at all and then, suddenly, all at once as government authorities sought to “revitalize” poor and minority neighborhoods during the 1960s and 1970s, in spite of community opposition. The most notorious case of this in Delaware is probably the building of Interstate 95, which required the demolition of hundreds of homes and the construction of a viaduct to carry the new highway between Adams and Jackson streets across the city’s west side.

But have you ever heard about what happened on the east side around French Street from 1961 to 1973? How the cultural and economic center of Black Wilmington — churches, businesses, restaurants, barbers, jazz clubs, theaters, and more — was demolished for a civic center that was never built?

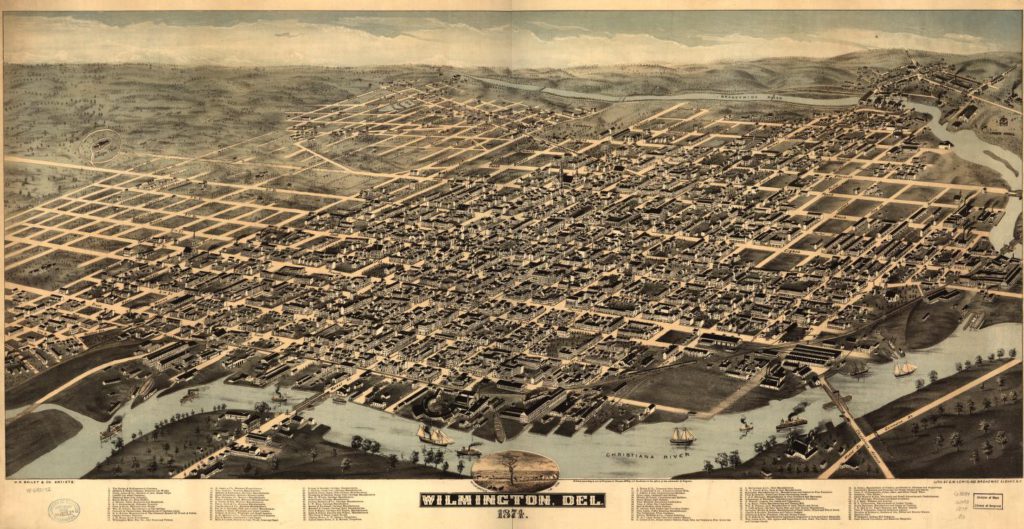

One hundred years before much of Wilmington’s east side was knocked down — in the aftermath of the Civil War — narrow dusty streets stretched north from the old train station on the Christina River into the center of town. The west side of Wilmington was still rolling hills and orchards while most urban development was located around the area now considered downtown, according to illustrated maps now held and digitized by the Library of Congress.

Albany, N.Y., G. W. Lewis. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Nearly all of the city’s residents — roughly 31,000 people in 1870 and 42,000 in 1880 — lived on this thumb-shaped plot of land between the Brandywine and Christina rivers.

And every year, on the last weekend of August, Wilmington’s population would grow by several thousand additional people as Black Americans from across the region gathered on French Street for the “Big” Quarterly celebration hosted by Mother African Union Methodist Protestant Church, founded in 1813 and renowned as the “oldest free colored church in America.”

“Train after train came pouring in alive with people,” the evening newspaper reported on the Big Quarterly in 1879. “The houses along Water street, the whole length of the square between French and Walnut Streets were as shores to a living sea.”

Before Cars, Pilgrims Traveled by Rail

The old train station at Front and French streets — owned and operated then by the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Company — was the regional gateway into the city for thousands who arrived for the Big Quarterly. Although pilgrims also arrived by river and road, back then it was the region’s sprawling railroad network that allowed people to travel to Wilmington from Dover and Harrington as easily as from Philadelphia or Baltimore, according to news reports and ticket sales published in the morning newspaper on Aug. 30, 1880.

When a train arrived at the station, hundreds of riders disembarked and walked up French Street for the Big Quarterly, only to be followed by another train and hundreds of more passengers, all eager to celebrate. The Big Quarterly, as reported by Wilmington’s daily newspapers as early as the late 1870s, was regularly compared to Mardi Gras (though smaller) with the entire east side alive with crowds, musicians, street performers, food vendors, and traveling evangelists. Crowd estimates in 1880 suggest that nearly 7,000 people traveled to Wilmington for the Big Quarterly that year, equal to about one-fifth the city’s population at the time.

The founder of Mother African Church, Peter Spencer, was born into slavery in Kent County, Maryland, in 1782, and moved to Wilmington in the early 1800s shortly after his manumission. A contemporary of Richard Allen, the renowned founder of the American Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Spencer founded Mother African on French Street in 1813 with help from Wilmington abolitionist Thomas Garrett. The following year, in 1814, Mother African held the first “Big” August Quarterly celebration.

The Big Quarterly evolved over the decades following the Civil War from a religious festival into a broader celebration of Black culture and the role Delaware’s abolitionist community played in the gateway north via Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad. Wilmington was the first stop in a free county for many thousands of refugees escaping slavery in the southern states, including Frederick Douglass, who passed through Wilmington on his way to Philadelphia in 1838. The Big Quarterly was held at Mother African on French Street for 156 years, until 1969, when the historic church building, along with much of the rest of Black Wilmington, was torn down.

Such it was that every August thousands of Black Americans would congregate in Wilmington for what was, at least in these parts, the biggest party of the year.

“Characteristic greetings and enthusiastic handshakings marked every moment. One young couple, probably brother and sister, possible lovers, buried themselves in each other’s arms and exchanged warm and resounding kisses,” according to one report in the evening newspaper on Sept. 1, 1879. “Before all had left the neighborhood of the [train] depot, the moving mass was extending far up French street,” where “vacant lots and door yards in the upper part of that thoroughfare had been improvised as restaurants.”

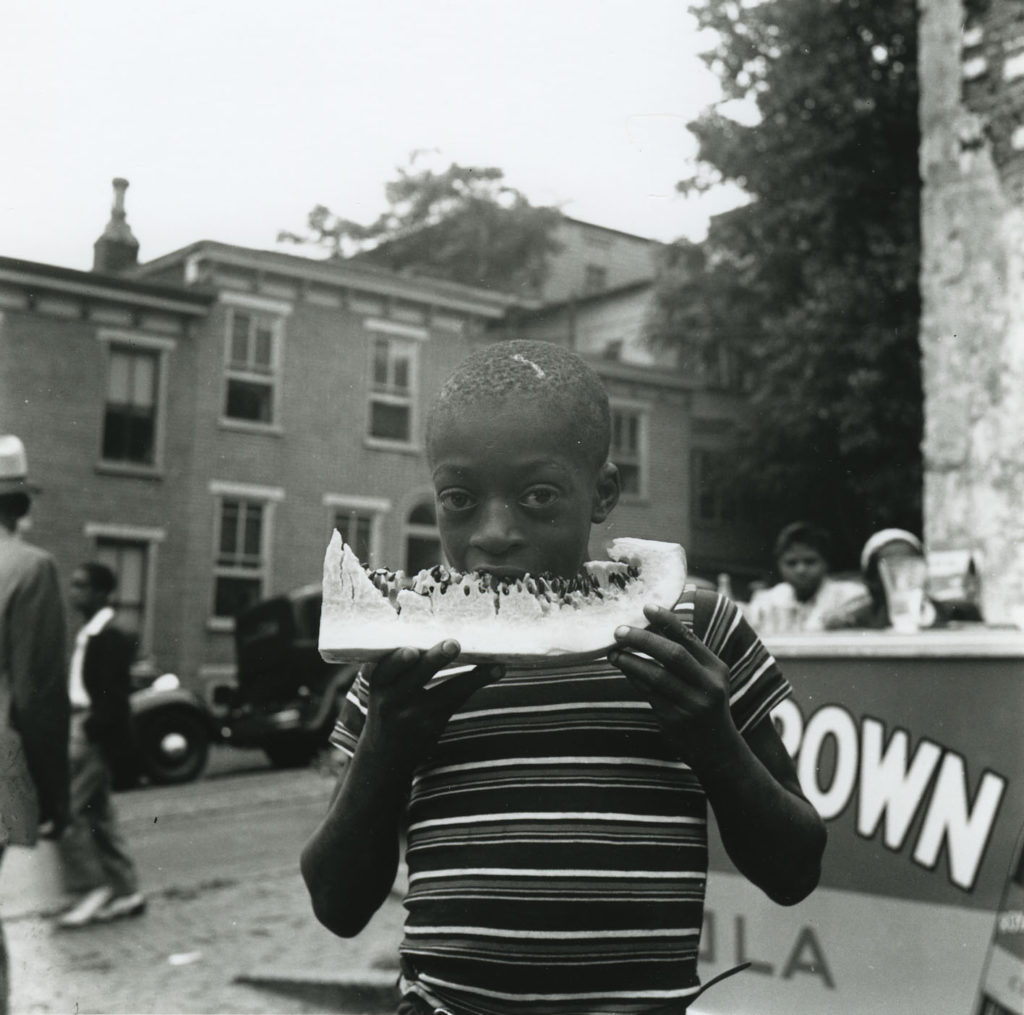

Along the sidewalks of French and King streets, thronging crowds moved past vendors selling “watermelons, cantaloupes, baskets of peaches, apples and other fruit and tables of all sorts and sizes spread with boiled ham, cakes and pies, tea, coffee, pickles,” and other sundries, “while the smoke of the little outdoor cookstoves and the fragrant steam from boiling coffee ascended in odorous clouds that permeated the atmosphere for squares in all directions.”

Although the atmosphere was festive like Mardi Gras, the Big Quarterly was still a religious gathering where the faithful, filled with religious fervor, would worship in song, both in the church and on the streets. On Sept. 1, 1884, one local reporter recounted a spontaneous chorus of “Come Ye Sinners” on French Street:

Come here, sinners, come here first;

Trust to the Lord — you won’t get lost.

Come here sinners, and escape his ire —

Come here sinners before your soul’s on fire.

According to the reporter, “This was sung with such a power that the very trees themselves seemed to tremble under the effects of it . . . Everybody seemed to be happy and joyful and full of the spirit of their religion, but perfect order prevailed upon the ground.”

Wilmington’s “Black Wall Street”

Not much about the Big Quarterly apparently changed from year to year, that is, according to descriptions in the newspaper. During the 1920s and 1930s, for example, descriptions of the Big Quarterly aren’t much different from 50 years earlier, except for the presence of cars. “Beginning Saturday afternoon and continuing on up until last night, the pilgrims flowed to this city,” according to a report in the morning newspaper on Aug. 30, 1926, which claimed 10,000 attendees from “as far away as Connecticut.” The report continues:

They came on trains, they came in automobiles, many of which had for days and days been groomed and bound together with ropes and wires for the triumphant entry into the besieged city . . . French Street assumed the aspect of an oriental bazaar, with mendicants grinding hand organs, rendering vocal selections to the accompaniment of tambourines and guitars. All along the street itinerant preachers like the prophets of old, exhorted the people to forsake the flesh pots of Egypt, and bellowed psalms at them.

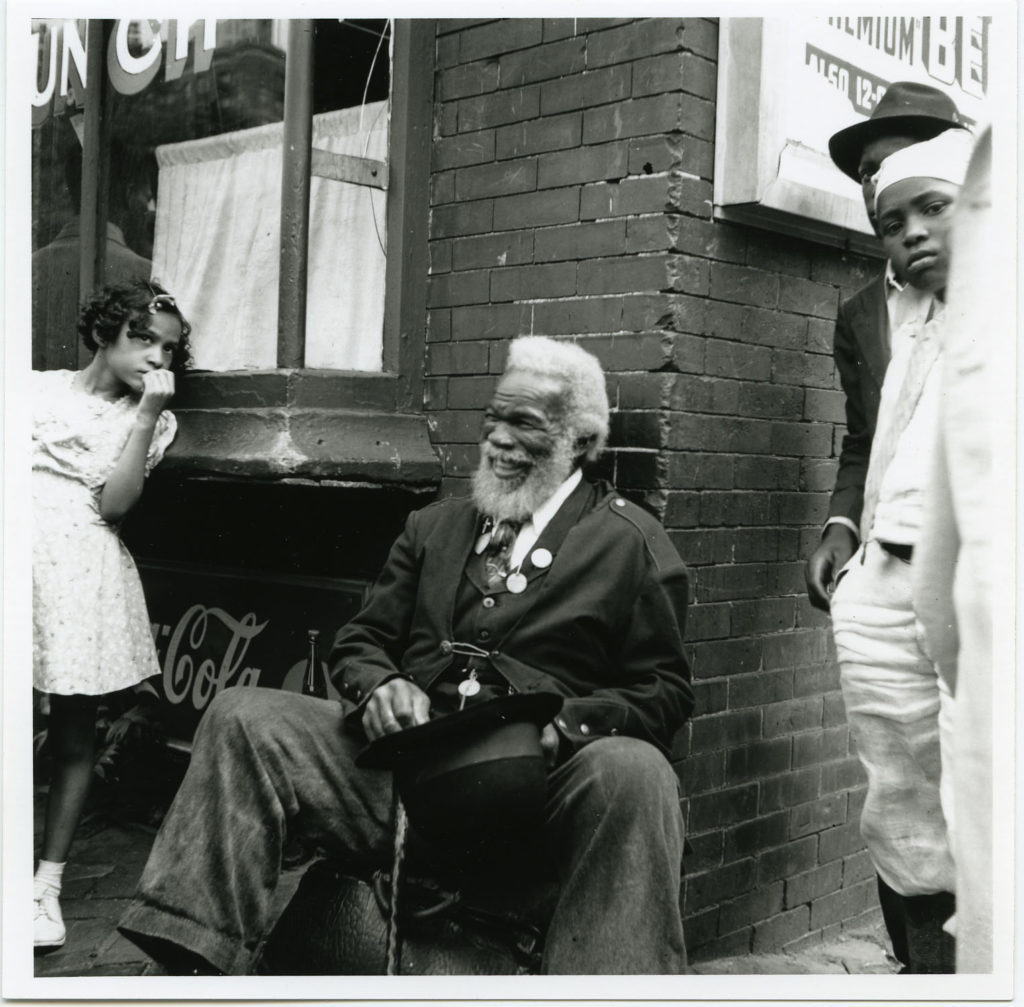

Images from the 1939 Big Quarterly show large crowds mingling on French Street, with men wearing pork pie hats and white shirts — some in suit jackets — and women mostly wearing white or floral pattern dresses. Food vendors lined the sidewalks and evangelists roamed the streets rattling tambourines and preaching the word of God. French Street was closed between Seventh and Tenth streets, although crowds were dense across the east side. According to newspaper reports, 15,000 people attended the Big Quarterly that August weekend, the largest gathering in many years, with an estimated 3,000 attending religious services at Mother African for prayers for “peace among the nations of the earth,” which days later would erupt into the most destructive war the world had ever known.

Throughout all this, Wilmington was a segregated city. Prior to the Civil War, the east side of Wilmington was one of the few places where Black families were allowed to live and form communities. However, because the Emancipation Proclamation only freed enslaved persons in Confederate states, slavery was not technically outlawed in Delaware until December of 1865 following the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which Delaware did not ratify until February 1901.

Delaware was also one of 17 states that still had segregated school systems in 1954 when Brown v. Board of Education struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine that was common across Jim Crow states. Brown was one of five school segregation cases that the Supreme Court combined into a single ruling that also included Gebhart v. Belton, which was filed in Delaware in 1952 by attorney Louis Redding, the first Black man admitted to the Delaware bar who also served on the NAACP legal team for Brown.

For many years, says longtime Wilmington resident Kamau Ngom, who moved to the city in 1951 when he was just 8 years old, Black churches were the only “safe” or “legitimate” places where Black people could actually gather, let alone host a regional celebration that drew thousands of attendees, especially prior to the Civil War.

“No other organization,” he says, other than Mother African, “could have done that safely, or at all.”

After the Civil War, Wilmington’s Black downtown — which centered around French, King, and Walnut streets — blossomed for over a century in part because Jim Crow segregation in Delaware demanded that Black entrepreneurs establish their businesses in Black neighborhoods with the intent of serving Black customers.

“Segregation was different here because we were a border state — like a person who can’t make up their mind,” said Ngom, who recalls seeing civil rights protests in Wilmington in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the social and cultural zeitgeist of Black Wilmington and beyond was on French Street, even while school segregation persisted until 1967. Despite racism, segregation, and violence, including the lynching of George White in 1903, Black Wilmington soldiered on, communities thrived, and the Big Quarterly continued uninterrupted for over 150 years.

“What was it like? The best comparison I can think of is Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” Ngom said. “But it wasn’t just Wilmington’s Black Wall Street because other surrounding communities that were Black depended on the east side for services.”

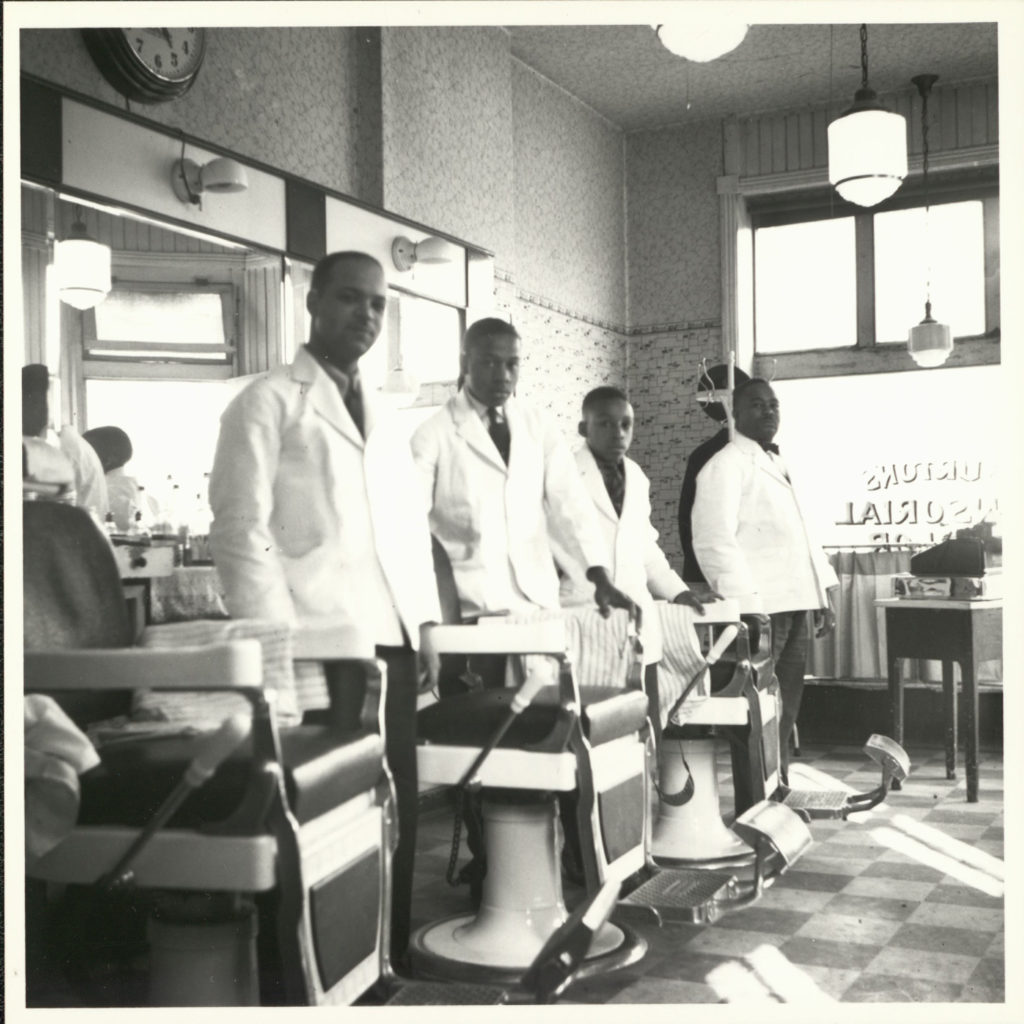

Traveling around Wilmington’s east side, pilgrims attending the 1939 Big Quarterly could get something to eat at Miss Elsie’s Chicken Shack at 1200 Walnut Street, or catch a show at the National Theater at 820 French Street. A couple blocks over, men could get a haircut at Burton’s Parlor at 801 Walnut Street or, for women, Na’s Beauty Shoppe at 429 East 11th Street. They could get a soda and listen to music at the Spot Grille at 703 French Street or Bill’s Cafe at 312 East 8th Street. During prohibition, one could even get an alcoholic beverage at Daisy Winchester’s fun time house on Krund Street.

There was also music. Lots of it. A thriving community of jazz artists flourished for decades on Wilmington’s east side, including Peck Morris and the Radio Boys, the Deuces of Rhythm, Joe Thomas and His Royal Swingsters, and more, according to historian Steven Leech in his book “Boysie’s Horn: The History of Jazz in Wilmington in the 20th Century.” Unfortunately, few recordings of these early Jazz artists have survived, with an important exception. Clifford Brown was born in 1930, and in his short life he would leave an indelible mark on jazz music, beginning in the school band at Howard High School. Clifford attended jazz lessons with legendary saxophone player Robert “Boysie” Lowery in the basement of his home on Pine Street.

“At the turn of the 20th century, Wilmington was a quiet city where two industrial monoliths, the duPonts and the Bancrofts, made the economy hum, kept Jim Crow order, and set the cultural tone,” writes Leech. In spite of that, jazz thrived on Wilmington’s east side.

“There are three cities jazz came from: New Orleans, Kansas City, and Wilmington,” Delaware disc jockey Maurice Sims famously declared. “New York and Chicago are where jazz went.”

Criminalizing the Quarterly

What were the Big Quarterly and Wilmington’s east side to Delaware’s civic and business leaders?

At times, perhaps, they reacted to the Big Quarterly with novel curiosity, but racial anxiety was pervasive. Just below the surface lurked a fear of disorder and lawlessness, which were present in nearly every newspaper report of the Big Quarterly for more than a century. The local newspapers, after all — where most literate residents would have read about current events — were owned by wealthy white industrialists and written by white journalists for a predominantly white audience. By 1911, both of Wilmington’s daily newspapers had been captured by members of the du Pont family.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the newspapers played an important role in spreading anxiety and rumors about the Big Quarterly. In 1879, following complaints posted in the newspaper, Wilmington Mayor John Allmond issued orders that forbid vendors at the Big Quarterly from setting up on sidewalks and in the streets. The following year, reports of smallpox in Camden, New Jersey and Philadelphia prompted public officials to call for the Big Quarterly to be canceled, which local newspapers amplified. However, there were no cases of smallpox in Wilmington and the Big Quarterly continued without incident.

Reports of crimes committed during the Big Quarterly were regularly featured in Wilmington’s daily newspapers. Even when the Big Quarterly was peaceful, the specter of violence was not far off for many newspaper reporters. In 1928, one report in the evening newspaper read, “From the viewpoint of disorder, yesterday’s celebration of Big Quarterly was unique. Not a single cutting or shooting affray occurred . . . Extra vigilance by the police is believed to have been an important factor in preventing disorders which in the past have marred the observance of Big Quarterly and ended with scenes of violence, bloodshed and sometimes death.”

The reporter mentioned no specific instances of violence from previous years but was likely referencing the 1927 Big Quarterly, which attracted more than 8,000 attendees, including several people who got into a fist fight, and when police tried to break it up one was slashed in the arm with a knife. There were no serious injuries. According to newspaper reports, that was the only disturbance. Despite this, days later, the evening newspaper included an editorial calling for the end of the Big Quarterly: “The celebrations are no longer necessary, and the law should prohibit them.”

Despite the overt fear mongering, over one hundred years of newspaper archives provide some important perspective. Given the racial anxiety of the newspapers’ white reporters, decades of reports regularly note “remarkably orderly” gatherings during the Big Quarterly, showing that orderly gatherings were the norm and any disturbances usually amounted to little more than a fist fight. But even one fight was enough to raise alarm bells in white communities.

Throughout all this, according to Delaware poet Alice Dunbar Nelson, the powers-that-be in Wilmington would “gravely shake their heads and predict that this will be the last of the Big Quarterly,” but all to no avail.

“And each year sees a huge crowd, ever-changing in its characteristics and methods of enjoyment, but still the same restless, laughing, pleasure-seeking mass of dark humanity,” Nelson wrote in a special for the morning newspaper on Aug. 27, 1932. “The immemorial usage of meeting together on Big Quarterly is too deeply rooted in the minds and hearts of the Negroes of the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, or Delaware and southeastern Pennsylvania, to be broken up or rooted out.”

However, this began to change in 1961, when Wilmington police nearly incited a riot in front of Mother African Church. On Sunday, Aug. 28 around 3:00 p.m., Mother African honored its founder, Peter Spencer, with a flag-raising ceremony and church leaders laid flowers on his grave located beside the church. Around 6:30 p.m. that evening, according to reports, the jubilant mood of the festival began to change as police were called to disperse the crowd and reopen French Street. It was then that several police attempted to clear the street by driving their motorcycles toward the crowd, nearly “stampeding the people like cattle,” according to the evening newspaper.

Police initially said that the incident started when a motorcycle cop attempted to help a boy who was “knocked to the ground,” but that story quickly changed. Without providing evidence, police claimed a “fight between two men somewhere in the 800 block aroused curious bystanders . . . and made the crowd difficult to control.”

The local newspapers would go on to refer to the incident as a “near riot” and “melee” for the next several weeks, even though both community members and city council members said police — not pilgrims attending the Big Quarterly — “incited the disturbances.”

Councilman Joseph L. Wallace, who was Black, attributed the disturbance to “the lack of training of the police” and said “you can incite people by pushing them around,” adding, “you would have thought a bunch of hoodlums were being run off the street.”

Ultimately, two were charged for inciting a riot, although it’s not clear from newspaper reports if those arrests were lawful. The following day, the evening newspaper reported that a prominent Wilmington judge, Thomas Herlihy Jr., revived tribalist fears among white residents about the Big Quarterly and claimed that criminal gangs were behind the disturbance.

“We must meet this challenge to incite others against police,” Herlihy said. “It goes to the very essence of justice and orderly procedure in our way of life. Far from seeing any police brutality it seems to me that maybe the police are too courteous.”

Even though an internal report cleared the officers of wrongdoing, Black community leaders were outspoken in their criticism of the police and called for a public apology.

“The people are furious,” according to Councilman Wallace. “If the police hadn’t had pistols, there might have been mob violence.”

How did Wilmington’s newspapers cover the Big Quarterly the following year?

“The Big August Quarterly, scene of a near riot last year, went off without apparent incident yesterday,” read the first line of a report on Monday, Aug. 27, 1962, ignoring the role police played in the incident.

By the early 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing in Delaware and across the nation, and major demonstrations were prominently featured in Wilmington’s daily newspapers. In 1961, hundreds of activists were arrested in southern states for participating in “freedom rides” in protest of segregation laws, a seminal historical moment that would have been in the hearts and minds of everyone attending the Big Quarterly.

Over the next eight years, the country was rocked by massive civil rights and anti-war protests, urban revolts, and political assassinations. Even the Big Quarterly became the site of political protest in 1963, when bus tickets to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom were sold at the festival, which the morning newspaper described as a “plea for equal rights” as much as it was a religious celebration in observance of Peter Spencer and the legacy of Mother African Church.

During that time, fault lines between Wilmington’s predominantly white police and Black communities began to mirror those in other southern states and urban centers as Black citizens fought back against segregation and Jim Crow, which would ultimately erupt into days of street violence, initially during the Long Hot Summer of 1967 and again several months later following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. In Wilmington, local and state officials responded to riots by invoking martial law and, infamously, deploying the Delaware National Guard to patrol the streets of Wilmington, where they remained for nine months.

Wilmington’s business and political elite would grab hold of these narratives about disorder and lawlessness on the east side to justify tearing it down.

Part two of this series titled “A New Downtown for Wilmington” will be published next week.

(Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Mr. Kamau Ngom age in 1951 when he arrived in Wilmington. Mr. Ngom was 8 years of age in ’51, not 6.)