Third-party groups spent unprecedented amounts of cash in Delaware’s state and local elections in 2020. The shift away from campaign financing organized by political parties and their chosen candidates has accelerated and shows no signs of abating.

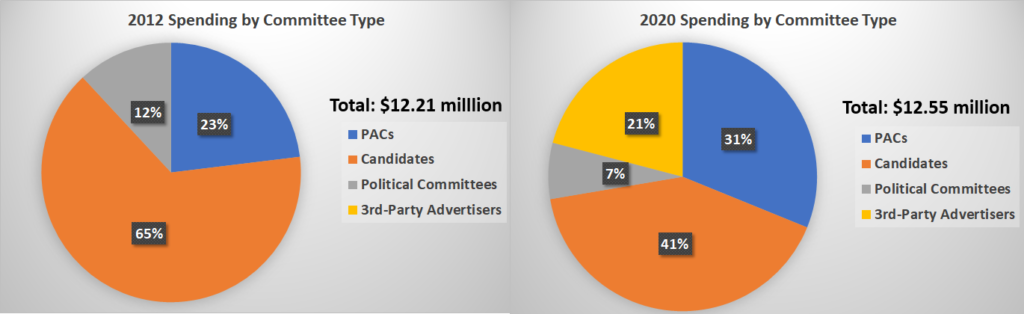

For the first time ever, third-party groups accounted for more than half of all spending tracked by the Department of Elections. Out of $12.5 million in documented expenditures, as of November 4, third-party groups like political action committees (PACs) and independent advertisers accounted for $6.5 million, or 52 percent of all dollars spent. Whereas spending by individual candidates and political parties continued a years-long decline.*

For Delaware voters who are concerned about dark money in politics, this is not good news. According to Pete Quist, Research Director at the National Institute on Money in Politics, what is happening in Delaware reflects a national trend. Third-party spending has increased significantly since the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC opened the door for unlimited contributions and independent expenditures by corporations, nonprofits, labor unions, and other groups.

“We’re seeing a trend around the country where these outside groups are playing a larger role in local elections than ever before,” Quist said in an interview with the Delaware Call. He added that in the 29 states from which his organization collects data, independent spending increased by 75 percent between 2014 and 2018, from $367 million to $650 million.

It’s no longer unusual to see competitive races flooded with cash from outside groups. If this trend continues, Quist thinks voters can expect even further concentration of political influence and decision-making among a handful of wealthy megadonors.

“This is part of the nationalization of state politics,” Quist said. “And the aggregation of power by these groups is cause for concern.”

“UNUSUAL” SPENDING BY “DARK MONEY” GROUPS

What’s different about Delaware, however, is that spending by candidates and political parties has declined yet, the total amount spent in each election has remained relatively stable.

Back in 2012, expenditures by candidates and political parties accounted for three-quarters of all dollars spent. That same year, legislators amended the state’s election laws with new disclosure requirements for third-party advertisements.

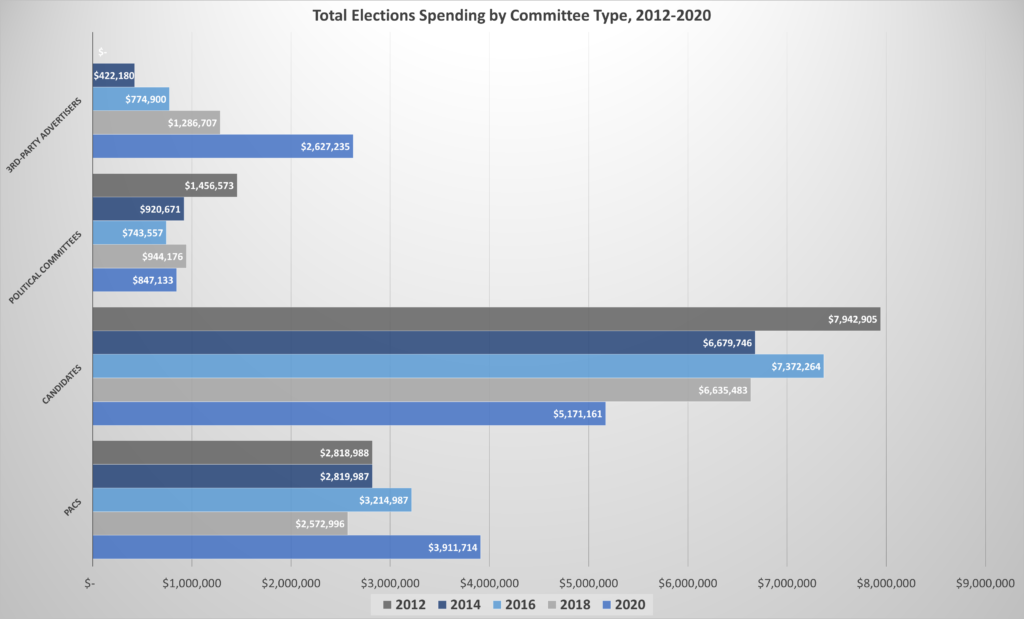

Since then, however, the share of spending by candidates and political parties has fallen significantly. Political parties spent about 40 percent less in 2020 than in 2012. Likewise, spending by candidates is down 36 percent, from $7.94 million in 2012 to $5.17 million in 2020, according to the Delaware Campaign Finance Reporting System.

Meanwhile, the difference in total spending between 2012 and 2020 amounts to slightly more than $340,000. So Delaware’s elections are not getting more expensive; it’s just that the money is being spent differently.

“It is unusual that candidates are spending less because across the country we’re seeing more expensive races,” said Quist, adding that irregularities of this sort may be more likely to happen in a state like Delaware, where the contribution limits are low for candidates but unlimited for PACs and independent advertisers.

In contrast to candidates and political parties, third-party groups are raising and spending millions more than in previous years. About 140 PACs spent more than $3.91 million in 2020, far surpassing the $3.21 million spent in 2016 and approaching the record of $4.02 million spent in 2008.

Independent advertisers, also known as “third-party advertisers” in the Delaware code or “dark money” groups by open-government advocates, spent $2.62 million in 2020, or more than twice as much as in 2018. In fact, expenditures by independent advertisers have doubled every election since 2014, when the Department of Elections began tracking spending by these groups. There are currently 41 active independent advertisers registered in Delaware, with the majority having formed since 2016.

Since third-party groups are not subject to the same contribution limits as candidates or political parties, it is not unusual for a single megadonor to write a check for $100,000 or more to support their preferred candidates. The problem, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, is that allowing unlimited contributions has concentrated in a very small group of people “more power than at any time since Watergate, while many of the rest seem to be disengaging from politics,”

In 2020 in Delaware, one out of every two dollars spent by PACs and two out of every three dollars spent by independent advertisers are tied to just two groups: A Better Delaware and Citizens for Transparency and Inclusion- both of which are funded by megadonors with deep pockets.

Shoprite CEO, Chris Kenny and DuPont Country Club co-owner, Ben DuPont founded A Better Delaware in 2019. The group spent nearly half a million dollars supporting Republican state Senators Cathy Cloutier, Anthony Delcollo, and Dave Lawson. Cloutier and Delcollo lost their re-election bids. In late-October, the Delaware Democratic Party filed a complaint with the Department of Elections alleging illegal coordination between the group’s PAC and the campaigns of Cloutier, Delcollo, and Lawson. Election Commissioner Anthony J. Albence, an appointee of Governor John Carney, sided with the PAC.

Citizens for a Pro-Business Delaware operates the other political group, Citizens for Transparency and Inclusion. Formed in 2016, by the former TransPerfect CEO to criticize the decision by Delaware’s Chancery Court to break up the now-defunct translation services company, the group promised to spend at least a million dollars attacking John Carney. Carney accused them of running misleading TV advertisements during the final weeks of the 2020 campaign.

Although both PACs claim to be nonpartisan, it appears as though virtually all of their spending was either for Republican candidates or against Democratic candidates.

*NOTE: Expenditure totals for PACs exclude dollars tracked by the Delaware Department of Elections but spent in out-of-state races