This story is being co-published by the Delaware Call and the Invisible Institute, a Chicago-based nonprofit public accountability journalism organization.

How easy should it be for a police officer who has left one department due to misconduct to get a job with another? And does the public have a right to know about that officer’s checkered past?

Despite passage of two police reform bills in 2023, Delaware remains one of just 15 states that keeps data about police officers that the state has certified, and where they work, secret, according to a nationwide reporting project.

This makes it impossible for citizens and journalists alike to monitor the state’s oversight of so-called “wandering officers” who switch departments only to continue patterns of aggressive behavior toward civilians.

Now, Delaware’s culture of police secrecy is being challenged in court. A lawsuit filed last week on behalf of Delaware Call is seeking data held by the state Police Officer Standards and Training Commission (POST), which tracks all law enforcement officers currently working in Delaware, and which agencies employ and have employed them.

It’s some of the most basic information about public employees that most states around the country release — including Delaware’s neighbors Maryland and New Jersey.

Tracking down “wandering officers”

Since 2022, a national news coalition convened by Big Local News, a program of Stanford University’s Journalism and Democracy Initiative, has sought data on police certification and employment history from every state. This coalition includes Delaware Call and the Invisible Institute, a journalism nonprofit based in Chicago.

In states where data on police certification and employment are available, investigations have shown gaps in state oversight systems that allow cops with criminal pasts to be rehired. Likewise, reporters have exposed police chiefs in small towns or school districts who overlook histories of misconduct to hire significant numbers of “wandering officers.”

Delaware Call then filed the first step in a challenge to a FOIA denial — a petition to Attorney General Kathleen Jennings — arguing that the cited exemptions were inapplicable and that the state has a responsibility to provide the requested data, even if it’s not maintained exactly as requested.

Texas researchers who were able to access the state’s police employment data found that the system for preventing wandering officers is “broken,” leading to reforms working their way through the state legislature.

In Florida, law professors who requested the state’s data found that wandering officers are not only more likely to be fired at their new department, but also to garner more sustained complaints about their “moral character.” They found that, at “any given point” during their three-decade-long study, an average of 3 percent of all of Florida’s officers — around 1,100 — had previously been fired by another agency in the state.

Residents “should have the right to investigate [if] bad cops are going from agency to agency,” said Chris Burbank, a former longtime chief of the Salt Lake City Police, in an interview. “That’s where there should be more public disclosure on those things, as opposed to hiding it away.”

Use of force, from Delaware misconduct to Maryland transparency

Perhaps the most well-known example of a “wandering officer” in Delaware is Thomas Webster IV, who racked up 29 use of force complaints with the Dover police before he was arrested and charged with assault for kicking and breaking a man’s jaw in 2013.

When Webster went to court on the assault charges two years later, the jury wasn’t allowed to hear evidence of those 29 complaints, and he was acquitted. Two months later, he left the Dover police for a $230,000 settlement and an agreement to not seek work there again.

Three years later, Webster was hired by the small town of Greensboro, just over the state line with Maryland. His history of altercations while serving as an officer in Delaware was noted by reporters and opposed by some residents, but Webster was hired nonetheless because he was “the best-qualified person that we had apply,” according to the then-town manager. “Because he was found innocent of everything,” she said, “there is no history.”

Webster was hired after newly elected mayor Joe Noon fired Jeff Jackson, the town’s longtime police chief, and hired Michael Petyo, a narcotics corporal with the Wyoming, De. police in suburban Dover. Jackson later told Dateline’s Lester Holt that Noon told him that he wanted “people to be scared to drive through Greensboro, and I said no.” Noon told Holt that he was responding to residents and business owners who wanted stronger enforcement of traffic laws.

Residents who found coverage of Webster’s criminal trial in Delaware contacted town officials with concern, as did LaMar Gunn of the NAACP of Central Delaware to warn them of Webster’s past, but Noon said that Petyo wanted to give Webster a second chance, and supported him.

Seven months after he was hired, Webster, responding to a call about a minor altercation between an older and younger boy, chased and pinned down 19-year-old Anton Black, who had bipolar disorder. After going limp while being held down by Webster, two other officers, and a citizen who helped give chase, Black died at the hospital.

Webster was ultimately decertified by the Maryland Police and Correctional Training Commissions (MPTC), the equivalent agency to Delaware’s POST that had previously granted Webster what’s called a “provisional certification” in Maryland in January 2018, based on his past training and experience in Delaware. That meant he had avoided going through the state academy, and was able to be immediately hired in Greensboro.

But that provisional certification, allowing Webster to easily pick back up his policing career three years after agreeing to never work for the Dover police again, was based on “numerous material omissions and misrepresentations” made by Petyo to state regulators in the paperwork he submitted for Webster, including a failure to provide information about his 2013 use of force.

After the MPTC was alerted to the gaps in Webster’s application by reporters, Petyo admitted that he had willfully withheld information about Webster in a plea agreement he entered into in November 2019, after which he was sentenced to three years of probation.

By that time, Petyo himself had left the Greensboro police and been rehired — back in Delaware, as a deputy chief with the Camden police, some 18 miles away.

However, Petyo attempted to overturn his own guilty plea after learning that one of the conditions of his probation was that he was barred from owning a firearm — meaning he could not work as a police officer.

Arguing that his previous lawyer, Stephen Tully, had provided ineffective assistance, Petyo’s new attorney, Ivan Bates, wrote in a motion that “at no time was Mr. Petyo advised by counsel that he would lose his right to bear and possess firearms as a consequence of his guilty plea. The fact that Mr. Petyo would lose his right to bear arms, and thus one of his most cherished civil liberties, was of critical importance to him. A fact not made aware to him until he reported for probation intake.”

His appeal was twice denied, most recently by the Maryland Court of Special Appeals in August 2022.

(Ivan Bates is now the Baltimore City State’s Attorney. In a statement, Bates’s office said, “Mr. Bates has represented many individuals during the decades that he worked as a successful private defense attorney before being elected to the State’s Attorney’s Office. Mr. Petyo, like many other defendants, hired Mr. Bates to represent him on his legal matter, as is his constitutional right.”)

Had Petyo’s appeal not been denied, though, it’s likely that he would still be an officer in Delaware, with supervisory authority over others.

“I’ve been advised by the police department in Delaware where he is working now that they do wish him to be back,” Tully, his first attorney, said in court in January 2020, during Petyo’s plea acceptance hearing. “They hope that he can be back and if he receives from this Court probation before judgment, then he can go back immediately to full-time police work where he’s at.”

The next month, a Camden resident asked the town council about the charges. According to the town minutes, then-Mayor Justin King “stated that it’s still under investigation with the department and with an open investigation they can’t comment. He added [that] the stories in the paper are not always 100% accurate.”

The town of Camden did not reply to a submitted request for comment about whether Petyo would have been reinstated with the department.

Regardless, Petyo’s misrepresentations about Webster’s past, leading to Webster’s certification in Maryland and subsequent involvement in the death of Anton Black, had another side effect: the repeal of Maryland’s Law Enforcement Officer Bill of Rights and the opening of most police disciplinary records in the state. The bill, passed by the legislature in an override of then-Gov. Larry Hogan’s veto, was nicknamed Anton’s Law.

What’s at stake?

Aside from helping residents and journalists be able to track wandering officers for public oversight, access to POST data could be crucial for public defenders, criminal defense attorneys, and wrongful conviction projects, experts said in interviews.

“I don’t think it’s fair to say that most of our cases are caused by, you know, the bad apples,” said Shawn Armbrust, the executive director of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, which handles cases in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. However, “the bad apples definitely contribute to wrongful convictions at a larger share than other people.”

“If the same things have been alleged in multiple cases,” Armbrust continued, it can be “corroborating what a client says, based on the fact that lots of other people have made the same allegations.”

So when data exist to suggest that an officer “does have that history,” she said, “it does make it more likely that there’s an innocent person or that there’s something wrong with the case.”

A list of officers with their POST unique identification numbers would be “incredibly helpful just on that baseline level to know who is working at which police department,” said Misty Seemans, the Family Court supervisor for the Delaware Office of Defense Services.

Because many officers could have similar names, having access to unique IDs “would help us in talking to our clients, learning where misconduct is occurring, learning where problems are being shifted.” Until last year, defense attorneys were blocked from receiving constitutionally required information about police witness credibility.

The work she envisions doing in Delaware is already happening across the border in Maryland — thanks to Anton’s Law.

Julie Ciccolini is a researcher who founded the firm Techtivist in 2023 after leading a police accountability data initiative for the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Using her experience building that project, which worked to develop internal police misconduct tracking databases for public defender’s offices, she is now working with the Maryland Office of Public Defender on building out the potential of Maryland’s POST-equivalent data.

Because an officer could escape being placed on a prosecutor’s list of officers with questionable credibility — often called a “Brady” list — by simply moving to the jurisdiction of a different prosecutor, having the statewide data in Maryland is crucial for the public defender’s office.

“If we don’t have that POST information, we can’t tell where this officer has worked before, because there’s just no identifier,” Ciccolini explained. “Being able to track this as members of the public and as defenders is hugely important to making sure that officers can’t evade misconduct.”

Defenders have used the database to track the movements of officers such as Joseph Donato, a Baltimore cop who racked up over 66 complaints over the course of his career, only to land a cushy position as a lieutenant with a community college police department.

In addition, a shortage of police recruits — felt nationwide and locally — has raised concerns for experts that the pressures to fill roles could allow more officers with histories of misconduct to be hired.

In addition to Webster, the movement of another officer between Maryland and Delaware — this time the other direction — exemplifies the disparity between the neighboring states.

In 2022, Wilmington officer Samuel Waters was first fired and then charged for multiple uses of force against civilians. But, as The News Journal reported, the “public almost never learned about” Waters because Delaware’s LEOBOR statute blocked most police data from release.

That history they almost never learned: Waters had previously been fired by the Cecil County, Md. Sheriff’s Office for losing his temper and making an obscene gesture at a Delaware court employee while driving to work. Despite this termination — and the Wilmington Police having the ability to access it — Waters was hired in Delaware.

After he was charged, journalists sought information about his history in both states — but were only able to directly access his Maryland discipline records, thanks to Anton’s Law.

Fighting for open records on Delaware police

In denying the open records request filed by Delaware Call, which sought Delaware’s police certification data, Deputy Attorney General Joseph Handlon first claimed that the state’s Department of Safety & Homeland Security and the Delaware State Police (which house POST and its predecessor, the Council on Police Training) aren’t in possession of the requested data.

He also wrote that — even if they did have such data — its release could be implicated by an exemption to the state Freedom of Information Act, which protects the release of records such as “response procedures or plans,” “building plans [or] blueprints,” or other similar records “which, if copied or inspected . . . could endanger the life or physical safety of an individual.” Finally, he cited the FOIA exemption protecting “personal privacy.”

Delaware Call then filed the first step in a challenge to a FOIA denial — a petition to Attorney General Kathleen Jennings — arguing that the cited exemptions were inapplicable and that the state has a responsibility to provide the requested data, even if it’s not maintained exactly as requested.

In response, Handlon expanded on the state’s arguments for the first time.

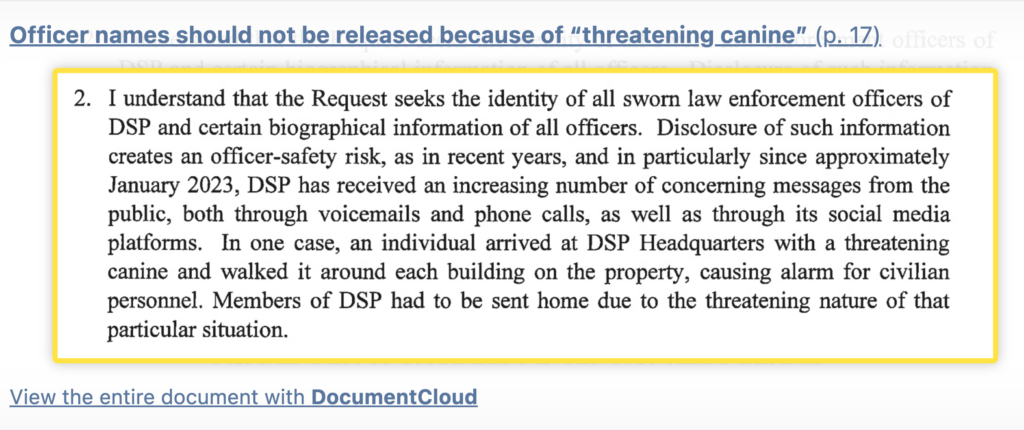

“There has been an increasing number of concerning messages from the public, both through voicemails, phone calls, and social media platforms, including one incident where an individual arrived at [DSP] Headquarters with a threatening canine causing an early release of civilian employees,” Handlon wrote. “Releasing the names of all troopers could jeopardize their safety based upon DSP’s assessment of threatening messages that it has received in the last year. Further, disclosure will also subject troopers to potential harassment or danger in the conduct of their official duties and personal affairs.”

In a brief opinion released in January, the attorney general’s office upheld the decision of Handlon, one of its employees.

The office found that the names of state police troopers — which are not the only officers that the request sought information of — could be considered to be part of a category of records including “specific and unique vulnerability assessments or specific and unique response or deployment plans, including compiled underlying data.”

“The DSP’s primary objectives include assessing vulnerable areas and deploying response plans to prevent, mitigate, or respond to criminal activity, and the identities of the officers, including those officers that are undercover or working in intelligence operations, are essential to these response and deployment plans,” Chief Deputy Attorney General Alexander Mackler wrote. “Disclosure of these assessments and response and deployment plans pose a safety risk to the involved officers and the public safety of the communities in which the officers operate, especially officers working in undercover or intelligence operations.”

In response, the ACLU of Delaware, which is representing Delaware Call, wrote in a brief filed Thursday that “the records sought here are… devoid of information that would endanger officer safety,” because they would offer no way to identify undercover officers, who generally do not use their real names.

“There’s a right to know who public employees are,” agreed James Nolan, a former Wilmington police lieutenant who served as a state public safety advisor during the administration of then-Gov. Tom Carper in the 1990s, and then as chief of the FBI’s crime analysis unit. He’s now a sociology professor at West Virginia University.

“My best guess about why they’re saying this is that they just don’t want to cooperate,” he continued. “It seems logical to them to just say no. Because, quite honestly, a police academy [class] graduates, and cameras are there. The names are in the paper. Some people go into policing at a particular time and then they go undercover later.”

But that’s not a reason to withhold certification data, he said. It may be possible that officers who work undercover might use their real name in doing so — though “why they would do so undercover, I don’t know” — but their names would eventually be revealed through the filing of things like search warrants, he said.

RaShall Brackney, a former Pittsburgh police commander who later served as chief of the Charlottesville Police Department, agreed. The kind of deep undercover policing that the state’s denial seems to anticipate simply doesn’t happen anymore. “If I’m undercover at some point, I’m out in the community. I’m making an arrest. I’m going to court,” she said.

The argument about harm to undercover officers “has always been out there,” said Brackney, who is now an African and African American Studies professor at George Mason University. “We’ve yet to find statistics where that has occurred.”

”The Court has the opportunity to state clearly that agencies cannot go beyond the scope of the FOIA to withhold such critical information because of a broad concern for public safety, especially when there is insufficient evidence that such safety risks exist at all,” wrote Benjamin Banker and Lexi Orgill, law students with George Washington University’s Public Justice Advocacy Clinic, which is assisting the state ACLU on the case, in an email.

In its brief, the ACLU argues that the state’s claims appear undercut by the publication of officer names elsewhere. POST publishes the names of officers who graduate from police academies or receive other certifications in its meeting minutes and agendas, and — as Nolan said — departments including the State Police, Wilmington, Dover, and New Castle County regularly publicize their graduating academy classes.

In addition, in response to FOIA requests from Delaware Call, many departments released records showing lists of employee names, and often other information like job titles or salaries, without issue. These departments include those for larger jurisdictions like New Castle County and small towns like Delmar, Camden, Laurel, and Milton. The News Journal also regularly requests and publishes salary data from state and local agencies.

“State agencies have twisted the application of FOIA to keep the public out, rather than bring the public in, as the statute is designed to do,” ACLU of Delaware legal fellow Casey Danoff said in a statement. “Access to basic information about what is happening in our communities is essential for public interest groups to advocate for improvements to our communities, and for the public to advocate for themselves.”

The AG’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Delaware doesn’t prevent wandering officers — and won’t let the public track them

The police reform laws that passed after much delay and deliberation in 2023 opened up some limited access to historically closed records about police misconduct in Delaware: written summaries of specific disciplinary or use of force cases, to be submitted by local police departments to POST and then published by the Delaware Criminal Justice Council. The first summary, about state alcohol & tobacco agent Joseph Dominic reselling cartons of cigarettes and lying about it, was released on Feb. 28.

But even though POST is required by law to track the employment changes of officers, in order for it to take any action, it is reliant on local departments to consistently and effectively discipline their own. State regulations prevent officers from being decertified in most cases unless they were first terminated by their employers or charged with a crime, and the cases that will be published by the CJC are limited to serious uses of force and a handful of specific disciplinary cases.

One of the reform bills passed last year newly instituted a rule that, on its surface, appears to address wandering officers. But the text of the law only requires police departments to have new hires sign agreements that their old personnel files can be reviewed. It does not, for instance, require that the hiring agency actually request those records — and, whatever they may show, those records would have no bearing on whether or not the officer could be hired, as long as they still hold a state certification.

Reporting in other states that have had similar requirements for years has shown that significant loopholes still exist with these systems, and that departments will sometimes misreport information on required state forms, or just omit it entirely.

In addition, a shortage of police recruits — felt nationwide and locally — has raised concerns for experts that the pressures to fill roles could allow more officers with histories of misconduct to be hired.

“Every agency is screaming for more police officer applicants, and so that makes hiring and the acceptance of officers who may have questionable backgrounds a problem for us,” said Patrick Solar, a former police chief in Genoa, Illinois, and a criminal justice professor at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. “To hire people to fill the ranks, we may intentionally or inadvertently lower our standards. It brings in the opportunity for officers who may run into trouble moving from one agency to the next.”

Reforms don’t negate the need for transparency around police certification and employment history data, said Christy Lopez, a former Department of Justice official who led the federal consent decree investigations into the Ferguson and Chicago police departments.

“It’s hard to imagine data that would be more important or relevant for the public to have,” said Lopez, who’s now a Georgetown University law professor, “and where the state would have less of an argument that that information shouldn’t be shared.”

Additional reporting by Shyanne Miller, Delaware Call.

Disclosure: Invisible Institute has a journalistic advisory role in the public records lawsuit filed by Delaware Call and ACLU of Delaware, but due to residency requirements in Delaware FOIA, is not a party to the litigation.