Now that the Delaware General Assembly has passed two police misconduct bills, HB 205 and HB 206, the question becomes, Will it make a difference?

For almost 30 years, police misconduct records have been secret in Delaware. Relatedly, the Delaware Council on Police Training (COPT) has been in charge of police training and certification issues for several years. The police misconduct records bill, HB 205, and the police oversight bill, HB 206, are a first step in an effort to increase police accountability and transparency. So, the next question is, can a first step make a difference?

Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” Myself and other police reform advocates have been able to envision the whole staircase for years, and we must have faith that the legislature will come back next year and improve upon this year’s efforts. And anyone who cares about this issue also has a responsibility to continue to fight for greater police reform and keep the faith that progress will happen. Faith is one thing; commitment is another.

In this essay, I will address what HB 205 will mean for the community and the criminal justice system, and what needs to happen next year to improve upon this law. Below is just a summary. Full bill language is linked above.

The Delaware Call has also provided space at the end of the piece for a few charts to help visualize what records could be made available, to whom, and the process by which the information will be disseminated.

What the public and attorneys will get under HB 205, the police misconduct records bill

Let’s start with the positive things about HB 205:

Some information will become public: Allows some sustained, serious police misconduct to be public by requiring the police to prepare, and the Criminal Justice Council to post online, “detailed narratives” of police misconduct.

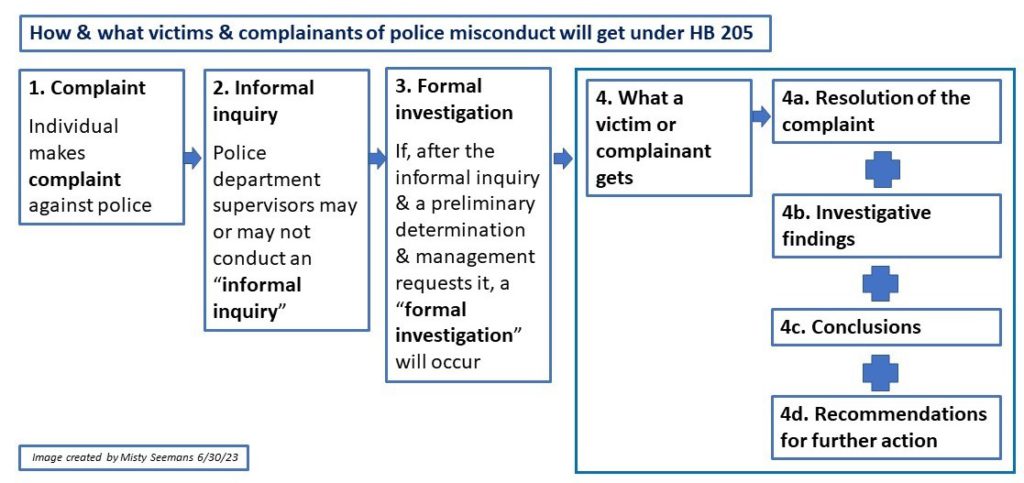

Victims and complainants will start to get answers: Requires the police to tell victims of police misconduct, or individuals who reported misconduct, what happened with their complaint. Previously, victims and complainants were not entitled to this information. See Chart 1.

Requires misconduct data to be public: Requires law-enforcement to report and publicly post data about all complaints, including those that are sustained, unsubstantiated, and result in other dispositions.

Police misconduct investigations must be completed: Closes a loophole by requiring that if an investigation is begun against an officer, it has to be completed. An officer cannot quit or retire in order to avoid an investigation.

Prevents jurisdiction hopping: Requires officers to agree to having their personnel records shared with other law-enforcement departments to prevent jurisdiction hopping of a problematic cop between agencies.

Some records can’t be destroyed for a long time: Requires all records related to sustained findings of serious police misconduct be kept for 25 years.

DOJ has to remind police to stay on top of misconduct: Requires the Delaware Department of Justice (DOJ) to “diligently” advise law enforcement to keep and share personnel records of sustained misconduct related to dishonesty. Basically, DOJ is now on the hook to tell the cops to do their job when it comes to reporting misconduct. (I’d argue this is already required by the Constitution, but another reminder doesn’t hurt.) 1

Law trumps cop contracts: HB 205 provides that law trumps contract. In other words, the police unions’ collective bargaining agreements do not supersede the changes that HB 205 makes. So, for example, police can’t contract out of public reporting requirements.

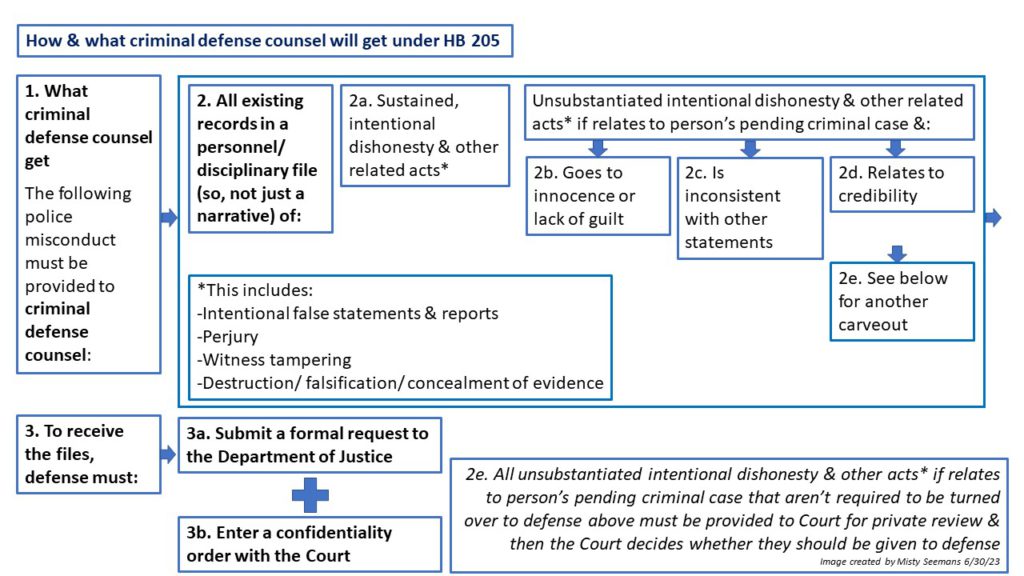

Gives criminal defense counsel dishonesty records: Creates a statutory requirement that criminal defense attorneys be provided with all police personnel records of sustained misconduct related to intentional dishonesty and other similar acts (perjury, witness tampering, and evidence tampering). This applies to all records, both retroactively and prospectively.

There is also a provision to report unsubstantiated dishonest acts that relate to pending criminal matters, so that it doesn’t take whistleblowers having to go to the DOJ to report police misconduct.

Now, let’s discuss the downsides of HB 205

HB 205 doesn’t get rid of the confidentiality clause: Police misconduct records will still be secret unless several procedural hurdles are jumped over and the misconduct falls into one of six specific categories. The confidentiality clause will still be on the books.

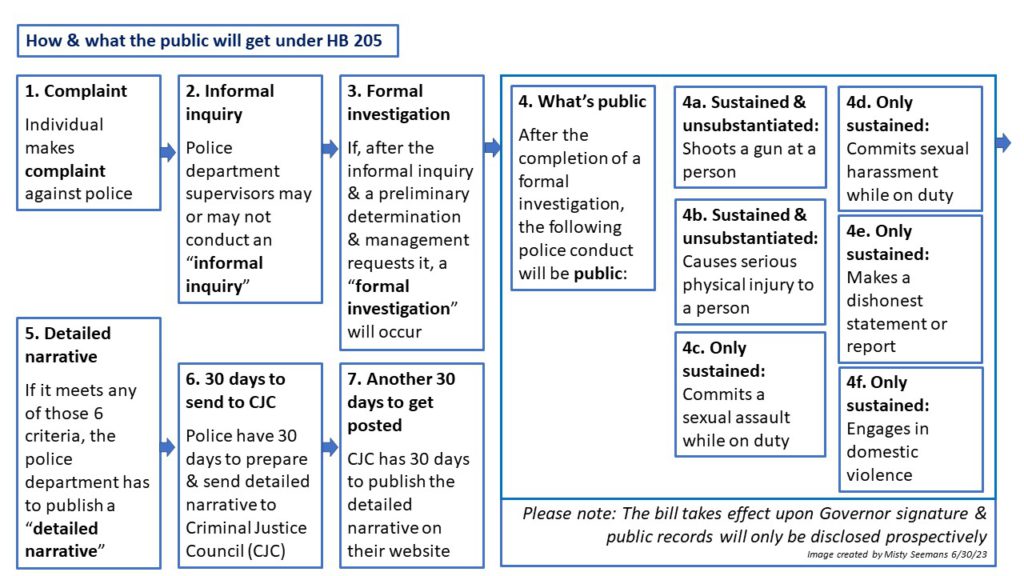

Not all police misconduct will become public: What becomes public is up to police, and police alone. Police misconduct will only become public if several hurdles are cleared.

Here’s how it will work. If someone makes a complaint of police misconduct, law-enforcement supervisors may, or may not, begin an “informal inquiry,” where they can ask the officer what happened.

If after the informal inquiry and after a preliminary misconduct finding, police management request a “formal investigation” take place, then the process can move forward. A formal investigation means that the police internal affairs unit looks into the claim. Depending upon whether the conduct fits into one of the following six categories, will it become public:

- Sustained or unsubstantiated conduct when a cop fires a gun at a person

- Sustained or unsubstantiated conduct when a cop causes serious physical injury of another. Serious physical injury most often means physical injury that creates a substantial risk of death.

- Sustained sexual assault while on duty

- Sustained sexual harassment while on duty

- Sustained dishonesty

- Sustained domestic violence

And, of course, the police determine what is sustained and write the summary that becomes public. Chart 2 shows all of the steps that have to happen before information becomes public.

These hurdles to public disclosure are important because just over the past several weeks, there have been multiple reports in the news of Delaware police officers engaging in misconduct. Those incidents are in the news because the police officer was criminally charged or the agency was sued. In the past several weeks alone, multiple Delaware police officers have been arrested for everything from allegedly taking and consuming drug evidence in a Millsboro Police evidence locker, to the Bethany Beach Police Chief being charged with a DUI, to a Wilmington Police officer being convicted of multiple crimes related to the excessive use of force and lying about it.

Not to mention, there is a recent report of a lawsuit by a former Wilmington Police Officer, claiming that city police routinely search people’s cell phones without a warrant. And then there was the latest report that the New Castle County Police officers who were involved in the shooting of Lymond Moses were suspended for only 4 to 16 hours. They were not disciplined for killing Moses, but instead reprimanded for not informing the Wilmington Police that they were in their jurisdiction, in addition to other issues like not properly reporting some of the details of the stop and chase of Moses. It does not appear that the police received any discipline for killing an unarmed man who was asleep in his car, woken up by police, and then tried to drive away.

So, looking at all of these recent examples, there are multiple procedural and scope issues that need to be overcome to have any information become public. Looking at the one above case alone – where the Wilmington Police Officer was recently convicted of misdemeanor assault for slamming a man’s head against a wall in a corner store – his excessive force would not be public under the new law. The officer caused physical injury (which is not public); not serious physical injury (which would be public, moving forward). However, he was also convicted for being untruthful about his actions. In an ironic twist, his lying about slamming the man’s head against the wall in a corner store, would be public under HB 205.

The public will only learn about future police misconduct: The public will only get serious police misconduct information and data moving forward. It’s not retroactive.

Delayed release of data: The public is not entitled to police misconduct complaint data until the end of 2024.

HB 205 doesn’t require all records be kept: OK, I get it. Records retention isn’t the hottest issue, but it’s so important. It matters for jurisdiction hopping as discussed above. It matters for data. It matters for wrongful convictions. HB 205 requires the retention of sustained police misconduct records related to the six public categories. In other words, there is no provision in HB 205 that retains records related to unsubstantiated police misconduct, police misconduct that falls outside the six categories of what becomes public, or records other than what criminal defense counsel get.

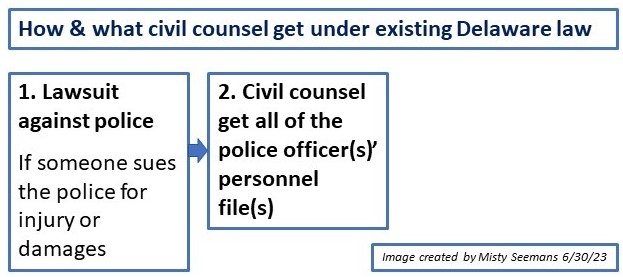

The defense counsel provision ain’t great: Under current Delaware law, attorneys who sue for injury or damages against police get everything in a police officer’s personnel file. That won’t change under HB 205. See Chart 3.

HB 205 instead expands statutory access to criminal defense attorneys. See Chart 4. My office has been fighting for the same access to records that civil attorneys get. If you compare Charts 3 and 4 you will see the significant differences between what civil counsel get and what criminal defense counsel will get under HB 205.

As I noted earlier, criminal defense counsel like me will get some stuff. But we are already entitled to that stuff under constitutional law. And we represent many people who are facing the rest of their life in prison, who are directly impacted by police misconduct, and are very often over charged. We should at least be able to get excessive force records and unsubstantiated conduct in case there’s a pattern of the same problems.

Furthermore, defense attorneys are only entitled to intentional dishonesty whereas the public is entitled to all dishonesty. Shout out to my lawyer friends who I’m sure can’t wait to argue the intentionality of dishonesty in police statements and reports!

One bad acronym replaced with another: It would be a personal failure on my part if I did not address that the Law-Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights (LEOBOR) will now be called Police Officers’ Due Process, Accountability and Transparency (PODPAT). We all will now have the unfortunate displeasure of having to say “PODPAT” when referencing this law. Leave it to law-enforcement to come up with another terrible acronym that sounds like a villain in an action hero franchise. If renaming it PODPAT is not a reason to repeal the whole thing, I don’t know what is.

Next steps

As HB 205 made its way from the House floor to the Senate, multiple legislators said that this is a first step. Let’s hold them to that. And let’s make sure that more is done next year. Real police reform is more than just a first step. REAL police reform requires the following:

- Retroactive access & retention

- Everything: Substantiated & unsubstantiated

- Access for the public

- Lawyer access

Important next steps include:

- All serious police misconduct records should be provided to criminal defense counsel, especially excessive uses of force.

- A consistent, statewide law relating to the retention of all police misconduct records, not just the stuff a police tribunal thinks is sustained.

- The release of more police data, including traffic and pedestrian stops and searches in Delaware. Who is being stopped and searched? How many stops actually lead to an arrest? This data in other places has shown terrible discrepancies in the race and ethnicity of people who are stopped by the police.

- Law-enforcement civilian review boards with meaningful community oversight powers.

So, will HB 205 make a difference? Personally, I will hope for the best, but expect the work to continue.

Misty Seemans is an Assistant Public Defender in Wilmington, Delaware

1Kyles v. Whitley, 514 U.S. 419 (1995).

Chart 1 – Victim Complaints

Chart 2 – The Public

Part 3 – Civil Counsel

Part 4 – Criminal Defense Counsel