Ever since they had acquired the H & H Poultry Plant in Selbyville in 1977, Mountaire Farms had been itching to get rid of the local union. The plant represented the only unionized facility in the entire Mountaire Farms network, staffed largely by vulnerable Hispanic workers who had long been exploited in rural agriculture in Sussex County. When the company finally won a decertification vote in 2021, they declared a lofty victory.

“After 44 years of union representation, the Selbyville plant takes a huge step forward today,” said Phillip Plylar, President of Mountaire Farms. “Our employees have just been asking for their voices to be heard, and today, they were heard loud and clear.”

In trying to play up organized labor’s grip on its workers, the company statement actually underplayed exactly how long the union had been a presence in the Selbyville plant. With a history that went back over 70 years, both the union and attempts to break it up were part of a much larger story that represented some of the worst of Sussex County’s small-town intimidation. In order to understand the decertification vote, we must look back at the first labor conflict in the Sussex County chicken plants, and how they combined anti-labor localism with racist backlash.

Rise of the Poultry Industry

As the legend goes, the first broiler chicken operation came to Delaware in 1923. Cecile Steele, wife of future Senate Pro Tempore Wilmer Steele, ordered 50 chickens to raise for eggs, but due to some miscommunication she ended up with 500chicks at her small farm in Ocean View. Looking to work with what she had, Ceceile decided to raise them for meat instead and sold them for a surprisingly good profit. In short order, she was raising broiler chickens full time and the rest of the community began to take notice.

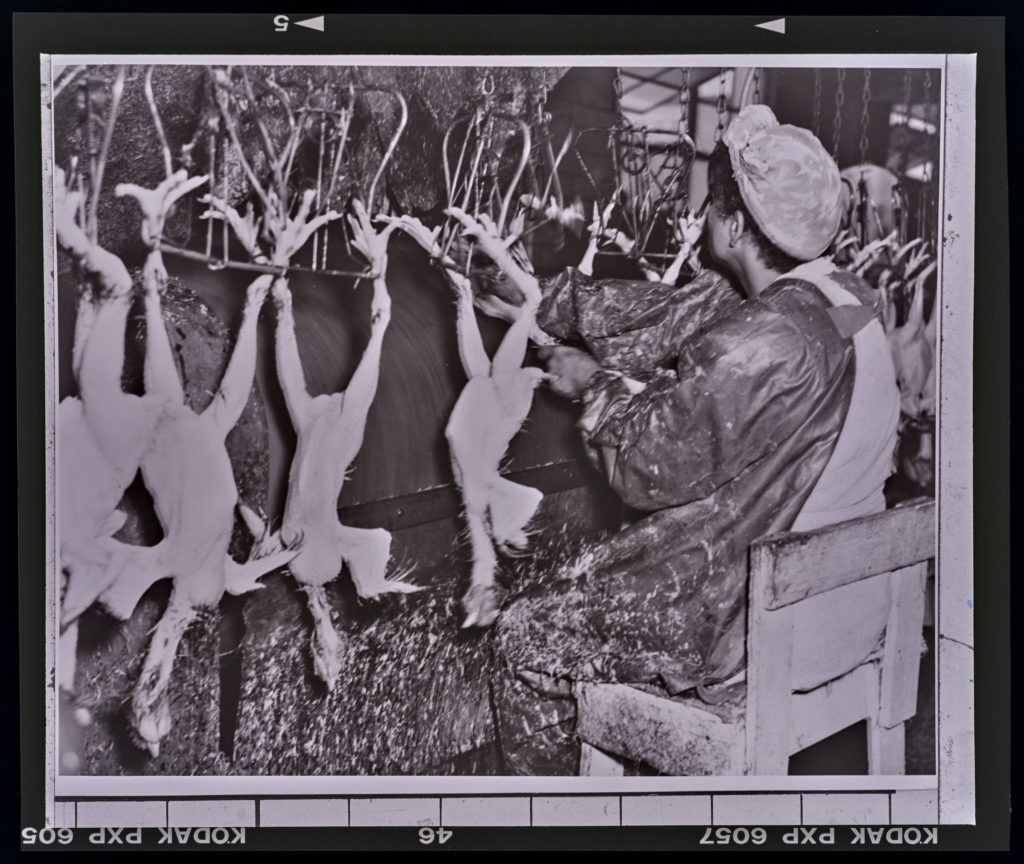

Several things enabled the rise of the broiler chicken industry in Delaware: the struggling of other local agricultural goods, the rise of trucking enabled by a new highway finished in the 1920s, and changing consumer attitudes around meat. Over the rest of the decade, the industry took off in the Delmarva Peninsula, especially centered in Baltimore Hundred in southeastern Sussex County. By 1928, there were over 500 chicken farmers in that area alone, and it began to spread to the rest of Sussex County and over the line into Maryland.

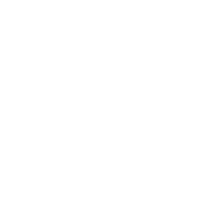

Most of these chicken farmers were independent proprietors who were already local to the area, building makeshift chicken houses that grew over time, as they increased their average annual production from 2,000 chickens in 1927 to 17,000 by 1943.

Following the maxim that the best way to make money in a gold rush is to sell shovels, new industries popped up around the new broiler chicken craze. Some started feed businesses that soon sprouted up across Sussex County, such as the Millsboro Feed Company started by future U.S. Sen. John J. Williams. Others got into trucking — taking chickens produced in Sussex County and using the new highway to sell them in Philadelphia and other northern cities.

One of the most lucrative businesses turned out to be chicken processing, as the first successful plant was started by U.S. Sen. John G. Townsend in Selbyville in the late 1930s. Processing plants took chickens from local farmers and did the work of slaughtering, dressing, and packing them locally, a process which had historically been done in the larger cities. After Townsend’s original success, new poultry processing plants cropped up along the lower part of the Delmarva Peninsula.

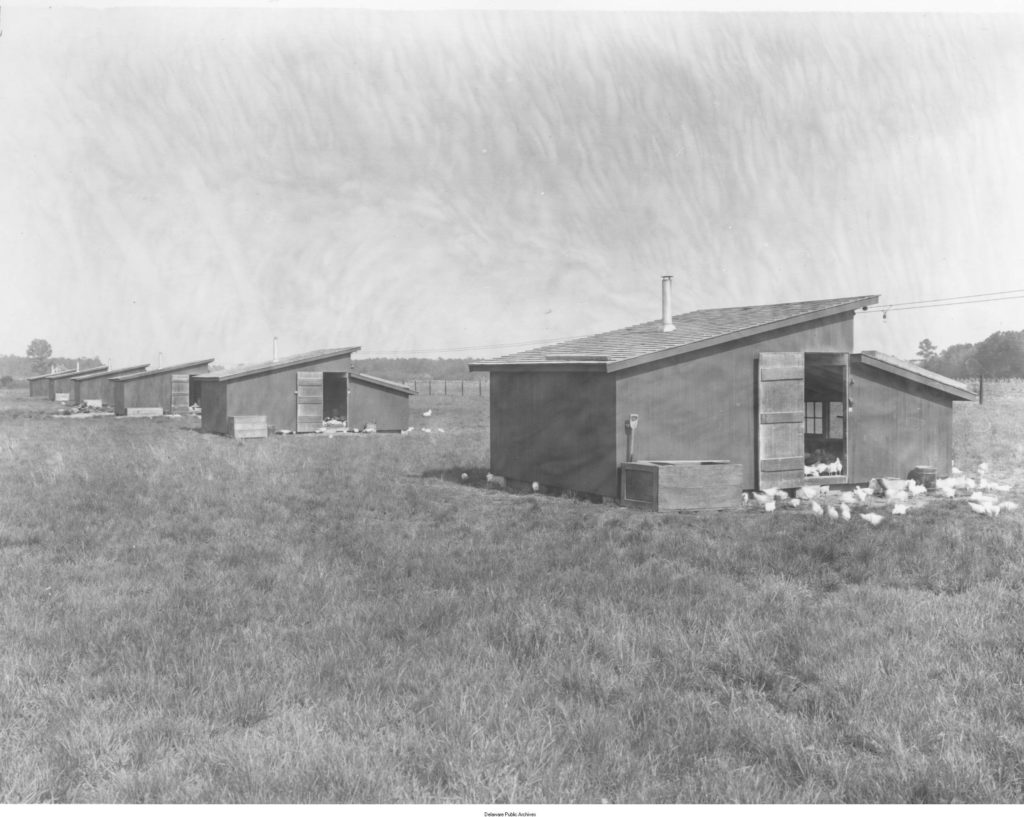

Sussex County now had a proper industry for the first time, which brought with it all the things that an industry implies. There was consolidation; in 1939, Sen. Townsend sold his plant to Homer Pepper, a local farmer and trucker who put together one of the earliest integrated systems with H & H Poultry. There was also exploitation, as a new industrial workforce in the processing plants had fewer local white farmers and more poor Black farmhands and laborers who still made up 20 to 30 percent of the area’s population. Poultry workers were paid paltry wages as the industry boomed.

The small-town familiarity of the region made it so that the new economic power of the chicken industry and the political power of the over-represented Sussex County were intimately related. Between 1928 and 1970, one of Delaware’s U.S. Senate seats was represented solely by men from Sussex County. Republicans John G. Townsend and John J. Williams were actively involved in the chicken industry themselves, and Democrat James M. Tunnel frequently represented local industry men in court.

Businessmen and politicians alike held to a small-town ethos. It was genteel and familial, but also highly restrictive and hostile to changes to the social order. This ethos would face its greatest challenge in World War II, which brought major changes to the poultry industry. In 1942, the Roosevelt Administration created the Office of Price Administration (OPA). Intended to make sure that rations were available across the homefront and the battle lines, the OPA set price ceilings on a variety of items, including chicken. With the price of feed allowed to rise by more than the cost of poultry, many in the chicken industry found themselves squeezed, leading to a sizable black market in Sussex County.

The Poultry Producers Association attempted to lobby the federal government and put a stop to the black market, but the tension created widespread distrust of the federal government and other attempts to interfere with the chicken industry among the small towns of the Delmarva Peninsula. In fact, it was this conflict which cemented John J. Williams as a conservative Republican and propelled his election to the U.S. Senate in 1946. The end of the war brought some relief, but many of the residents were now on high alert against any threat to their local business. Soon the industry would face a new challenge, this time from below.

Labor Divided

If the war had been a bad time for the poultry industry, it had been a great time for organized labor. Between 1935 and 1945, America’s unionization rate among private sector workers had rocketed from around 14 percent to over 33 percent. Much of this growth came from the same sort of federal intervention that local chicken producers despised, whether it be the National Labor Relations Board or the massive federal agreements between the government, business, and organized labor which made membership in unions the norm across massive industries.

However, this growth came along with the largest division in 50 years within the labor movement. In 1935, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) split in two over the question of whether they should prioritize the organization of non-skilled industrial workers in mass production industries like steel and auto. The new organization in favor of this broader form of organizing became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Over the next two decades, the two labor federations, AFL and CIO, would battle it out across nearly every state and industry within the country.

In Delaware, there was not much to battle over — initially. Most of the state’s industry was historically concentrated within Wilmington, and even there the labor movement had only been a marginal force. At the turn of the century, a set of largely building trade unions had helped organize Wilmington’s Central Labor Union, which coordinated the activities of labor in the city. But especially after World War I, many of these unions were relatively small and made up of moderate skilled craft workers.

It took the Great Depression and the National Labor Relations Act to kick Delaware labor organizing into high gear. The most memorable push was a massive organizing campaign by Teamsters Local 107 in Philadelphia which organized several hundred truck drivers and helpers in Wilmington. When local employers refused to negotiate, the Teamsters launched a strike of over 600 workers which shut transportation down and quickly won them a near doubling of their wages. In response, membership skyrocketed to nearly 4,000, kicking off a new era of unionization in Wilmington.

The Teamsters were affiliated with the AFL, but their success was quickly met with the arrival of the CIO into the city in 1937, who organized locals of textile workers and shipbuilders. The shipbuilders in particular turned into a large membership base as the industry became crucial during the war years, when the CIO also began organizing autoworkers en masse. By the end of the war, somewhere near 80 percent of industrial workers had organized with either the AFL or the CIO and Delaware union membership stood somewhere between 40,000 and 45,000.

Throughout this time, there had been little union activity outside of Wilmington. After all, any industry outside of the city was largely in industries that were more difficult to organize, including poultry processing. However, with the end of the war, both the AFL and CIO were feeling emboldened by their burgeoning membership and the implicit support of the New Deal liberal state, so they began to reach out to areas they had never dreamed of before; areas like Sussex County, Delaware.

The Chicken House of Labor

It is not clear exactly when the unions began to organize the poultry industry in Delaware. What is clear is that the AFL got there first. Throughout the 1940s, two AFL unions began to agitate the processing plant employees and the truckers. The processing plant employees were organized by Local 199 of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters (AMC), an AFL union, which had started by organizing butchers in Wilmington. The truckers were organized by Teamsters Local 876, which was also still affiliated with the AFL. Both unions were products of the nineteenth century and were well-established, and both seem to have made solid footholds into the Delmarva peninsula by 1945.

The AMC and Teamsters made their most public push early in 1951. On February 19, the Teamsters went on strike and were quickly joined by the AMC workers despite a lack of approval from the union itself. The plant workers requested a 25-cent-per-hour increase, while the drivers demanded a standard $79 rate for a set eight-hour work day instead of the per-trip fee they currently earned. The strikes never fully shut down the industry, but they contained over 600 workers and spread to chicken processing plants in Selbyville, Berlin, Millsboro, Milford, and Frankford.

By this point, the president of the Poultry Packers’ Association was Homer Pepper, who ran the H & H Poultry Company in Selbyville. As the head of the employers association, he would become the major figure in conflicts within the poultry industry over the next several years. Pepper got started in the chicken business as a teenager, raising chickens before opening his own trucking business in the 1920s. Over the years, he consolidated his business to include farming, processing, and trucking and had become one of the most prominent players in the Sussex County poultry business. Despite the fact that he ran off on his first wife and kids without paying alimony, he also had earned a reputation as a prominent, respectable man in his corner of the Baltimore Hundred of southeastern Sussex County.

Pepper was a major booster of Delmarva’s chicken industry, and he became frightened by the strike as it began to threaten not just his own business but the broader ecosystem of farmers and truckers. Seeing farmers turning against him and his fellow processors, he made a general appeal:

We acknowledge that the farmers are currently suffering to some extent, but we claim that both the employees and ourselves were injured by the strike, and we think that the farmers have a strong interest, which is in common with ours, and that is in avoiding having our costs in wages get out of line so that we can no longer produce favorable competition with processors in other areas. If our wage costs become too high, the poultry growers will suffer as much as we will. Georgia, for example, is mushrooming in poultry production.

While this appeal did not stop the strike, it did eventually end on May 13, 1951, on conditions fairly favorable to the employers. Truck drivers and plant workers received immediate pay increases of just five cents an hour and another three cents the following January. Such a lackluster result opened up the possibility for competition, and the CIO was happy to oblige.

In the closing months of 1952, organizers from the Delaware chapter of the CIO launched a blitz into the chicken plants of the Delmarva peninsula. Delaware chapter president Gilbert Lewis, staff organizer Frank Maloney, and local Selbyville worker Herbert Jenkins combined to challenge the AMC and Teamsters across a variety of plants. For reasons that would soon become clear, the drive was carried out almost entirely in secret until the representation election was held.

The results were a shock. Going up directly against the AMC and Teamsters across three different chicken plants, the CIO won a clean sweep. They now represented workers in H & H Poultry Company in Selbyville, Diamond State Poultry Company in Lewes, and the Millsboro Poultry Company. This left six other plants represented by the AMC, two by the Teamsters, and seven unorganized.

While it was a limited push, the decisive margins — as much as 165-86 in the Selbyville representation election vs AMC — showed a clear appeal when compared to the AFL-affiliated unions that had represented many of the workers up to this point. Unfortunately, the newspapers did not deign to interview any of the largely Black poultry workers to learn why they supported the union, but the CIO’s stronger practice of organizing Black workers historically ignored by AFL unions likely played a role.

After these victories, the CIO now had a foothold in Sussex County’s chicken industry. The new bargaining unit had been organized by the CIO as a whole, not an individual union, but it was quickly assigned to Local 262 of the Bakery, Confectionery, Cannery, Packing & Food Service Union. Local 262 itself was a subsidiary of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU), based in New Jersey. Once assigned, the new local got to work trying to negotiate a contract for the large Black workforce which had so recently been underwhelmed by the previous union’s efforts. This time there would be more of a fight.

The 1953 Selbyville Poultry Strike

At 4:00pm on Thursday, March 19, 1953, approximately 300 poultry workers walked off their shifts at the H & H Poultry Company and formed picket lines outside. For the previous two weeks, Local 262 had been negotiating with the plant, seeking a 30-cent increase in their pay over their existing 83 cents per hour. H & H offered just 5 cents, so the union went on strike.

Workers formed relatively orderly pickets around the plant, and the first afternoon was fairly uneventful. The first sign of trouble came that night when a picketer had parked his car across the entrance of the plant’s driveway to prevent trucks from leaving. When one of the truck drivers came up to the exit and called out to them to move the car, they refused, so the man simply drove his truck through and smashed the front of his car on the way out. No one was injured.

The next morning, the plant was operating at around 25 percent capacity, as plant management brought themselves and their families along with some sympathetic town volunteers to do the dirty work of chicken dressing. Picketing came and went throughout the day, but they didn’t block the workers coming in, and a crowd of largely white townspeople jeered at the largely Black picketers and told them to go home. Throughout the remainder of the day there was little outright conflict.

Then, on the evening of Friday, March 20, Local 262 business manager Herbert Jenkins was at home when noticed something bright outside. When he went to the window, he saw a ten-foot tall cross burning in the grass across the street, lit by hooded white figures. The next morning he took himself and his family over to his mother’s house in Frankford, but that night a crowd of cars drove to the field across from them and then turned off their lights, waiting in the dark. When the family called the police, the cars sped off. Selbyville Mayor Raymond Ringler laughed the whole incident off, declaring that the item burned in front of Jenkin’s home was not a cross, but a ‘V’.

At the picket lines, tensions also began to rise. On Saturday afternoon, a group of around 125 townspeople surrounded picketers at the plant and began to threaten them with pitchforks and knives. When one man pulled out a gun he was arrested, but his bail was posted by the owners of H & H. “We feel the civil rights of workers are involved,” declared Gilbert Lewis, president of the Delaware CIO. Lewis reached out to the governor and even had Walter White, president of the national NAACP, reach out to local officials, but neither intervention made a difference. When the union passed on potential names of the hooded cross burners to the state police, they were largely ignored, so they called the FBI.

The next week, the presence of FBI detectives and an increased state police presence combined with the rain to cool the tensions in the small town of 1,000 people. On Thursday, March 26, H & H and the CIO began negotiations in Georgetown for the first time since the strike, though they were unable to come to an agreement. Meanwhile, dozens of pickets continued outside the plant as some workers slowly began to return to work. By the end of the month, Homer Pepper announced that despite not having their full workforce, the plant was now operating at full capacity again with around a third of strikers joining the volunteer and white collar workforce that had been scrounged up after the strike.

Nevertheless, 200 workers enthusiastically voted to stay on strike, and the headquarters on DuPont Highway was buzzing. Their cause received an unexpected boost at the beginning of April when three other plants in Milford, Berlin, and Denton saw walkouts among their AFL-represented unions, all looking to achieve the same goal of a minimum $1 per hour wage.

However, the union battles earlier that year had taken their toll. Nearly all the plants had some mix of committed CIO, AMC, and Teamster members, and the unions did not seem to coordinate at all in their demands. Lacking clear direction, many members decided to stay at work, which allowed the plants to stay open. The AMC even refused to recognize the strike at the plant they claimed to represent, since the NLRB had not yet made a decision about their conflict with the Teamsters from earlier in the year. Ultimately, the strikes at the plants outside Selbyville fizzled out within days.

With no progress being made, tensions once again ratcheted up. One of the buses the company was using to transport scabs was burned in the driveway overnight, though the culprits were never caught. H & H began to threaten strikers more explicitly, saying that no one on strike would be rehired and eventually moving to evict the workers who had been living in company-owned housing. All the while, state police cracked down on picketers with increasing severity.

This stalemate came to a head on Thursday, April 23. After a few picketers had been arrested the day before, a larger crowd formed that afternoon and began to sing loudly. When a few strikers swore at the plant, they were arrested and fined, enraging the crowd even further. At that moment, a bus came out of the plant carrying the scabbing workers, so strikers pelted it with coal and stones, cracking windows and injuring one of the plant supervisors. A picketer set fire to one of the barrels on the property, and when Homer Pepper went to call the fire department his car was also pelted. Overnight, 30 strikers were arrested and brought to the county jail in Georgetown.

When Local 262 held a meeting the next evening to plan their response to this crackdown, their meeting house was suddenly surrounded with around 50 cars blocking them in. As they huddled inside, the town’s fire alarm went off and several engines were brought to the scene. The firefighters connected their hoses and began to blast the doors of the meetinghouse, nearly forcing their way in before the union officials called the police to settle things down.

This intimidation proved to be the climax of the Selbyville poultry strike, which ended how many strikes in Delaware did: confused defeat. Throughout April, the newspapers printed several accusations that Local 262 was using out-of-state staff, who were largely white, to negotiate on behalf of the local workers, who were largely Black. The message was clear: out-of-town radicals were using these simple workers to attempt to change the way things worked in Selbyville.

However, the CIO did not actually have nearly that much power, and the strike began to slowly come to a close. Limited picketing continued throughout the next several weeks, but it was ended by an injunction won by H & H from the Court of Chancery. With no chance of victory, many of the strikers simply moved out of their company housing and began to look for work and shelter elsewhere. Local 262 remained as the legal bargaining representative for workers in the H & H Poultry Company, but no wage increase was won in the strike.

Afterword

Almost exactly a year after the end of the strike in Selbyville, the Supreme Court handed down one of the most influential decisions in American History: Brown v Board of Education. Most schools would take a while to desegregate, but the town of Milford was pressured by the NAACP to take action immediately in the 1954-55 school year. The result was a complete white community revolt.

Many of the same tactics used in Selbyville in 1953 to successfully crack down on the strike were used right up the road in Milford to reverse the desegregation decision from the local school board. White mobs, burning crosses, and police indifference all combined to threaten the Black families and local officials to prevent progress that Sussex residents felt was being forced from outside sources.

“To understand these things and to give an honest account of it,” said one union man during the poultry strike, “you have to understand Sussex County and the way they feel about things. They don’t like unions.” The same could be said for integration and a variety of other things, and the small town mentality would continue to prevent the progress of the workers in the region.

The status quo mostly continued at the plant until the H & H Poultry Company was bought by Mountaire Farms the year after Homer Pepper’s death in 1976. A few years later, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters would join with the Retail Clerks International Union to form the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) in 1979, a union that would soon absorb RWDSU and Local 262.

For decades, UFCW continued to represent workers at the Selbyville poultry plant, but the makeup of those workers began to change. In the 1950s, the employees had largely been Black workers who were native to the Delmarva peninsula, but as the century came to a close, the chicken plants began to hire a more exploitable labor force: Hispanic immigrants.

When the pandemic struck in 2020, Mountaire Farms used the opportunity to finally achieve what Homer Pepper and his fellow chicken men could have only dreamed of 70 years earlier. With harsh restrictions in place in the name of worker safety, the company was largely able to limit the union’s access to the plant and launched a decertification campaign against their vulnerable workers. Represented by the National Right to Work Foundation, a local immigrant worker filed a decertification petition, and in December of 2021, the union was defeated by a massive 356-80 margin. The next year, even the remaining Teamsters representation was removed by 140-25.

The future of organized labor in the chicken business is unclear. Under the new Trump immigration and labor regime, it is as difficult as it has ever been to imagine a new union taking root in any of the unorganized plants that dot the Delmarva peninsula. And while Sussex County has been changing rapidly over the last couple decades, the small-town attitude is still deeply ingrained in local residents and local leaders, especially in places like Selbyville. However, if another effort is made in the coming years, they can look back to the lessons of the 1951 and 1953 strikes in Selbyville as a model for what to do — and what not to do.

Sources: Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress, The Morning News, Every Evening, Delaware, A History of the First State Vol. 2, Delaware Public Archives