Is it possible to organize a unified movement of the multi-racial working class? This is a question that has been asked by countless left and labor organizers throughout the years. When we look towards the goals of eliminating the evils of exploitation and oppression through the organization of a mass working-class base, organizers often look back to a few key moments in American history. Common touchpoints are abolitionism and the early Republican Party, the industrial unionism of the CIO and the New Deal, or the Civil Rights Movement and the Great Society.

However, when we look at our current situation in 2025, it looks a lot less like 1935 or 1964 and a lot more like the early 1880s. A social situation marked by backlash against racial and gender progress, a federal government and Supreme Court united in its hostility to labor rights, and an unstable and changing economy in which many of the previously most reliable trades were suddenly being automated and made more precarious.

In this era, conditions seemed about as hopeless for solidarity and building power as they do now. But it was out of these conditions that the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor was born. The Knights were the first ever truly national labor organization and the first major labor organization to organize the skilled and unskilled, men and women, Black and white, immigrant and native born. In 1886, they briefly surged to reach a membership of 700,000, orders of magnitude larger than any union in American history, before suddenly collapsing and going almost extinct within a decade.

As we look to build a working class coalition in the 2020s, we can learn from both the successes and failures of the Knights of Labor in the 1880s.

A Brief History of the Knights of Labor

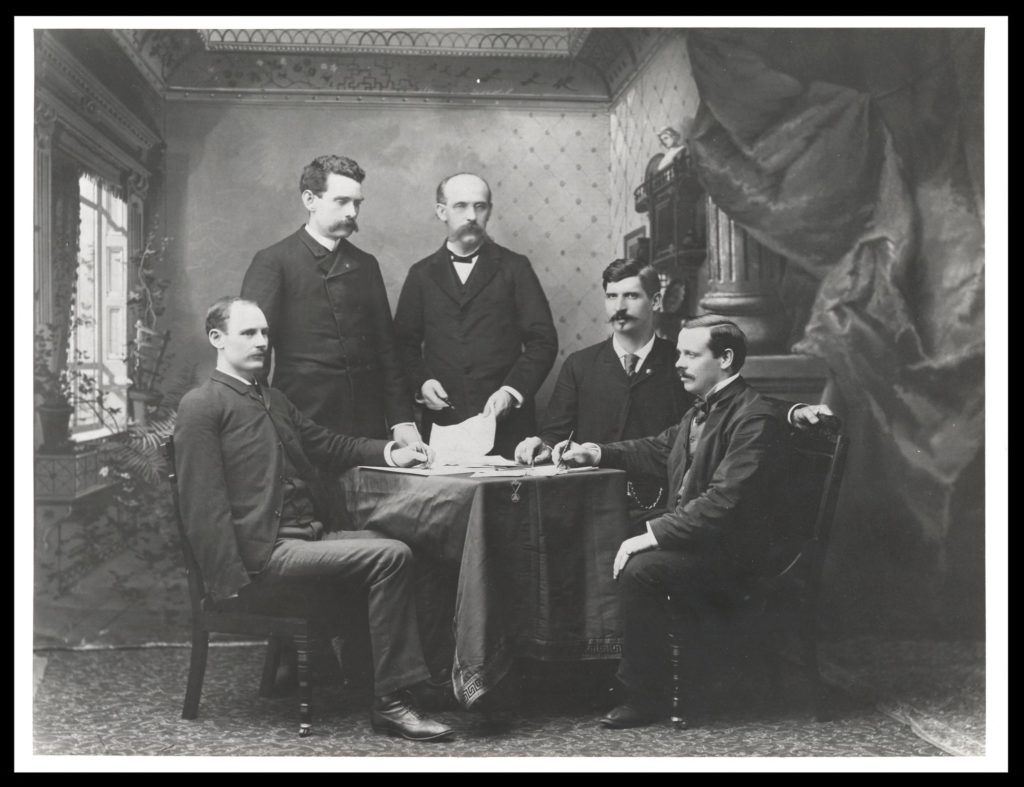

The Knights of Labor was never actually a union, at least how we think of it today. They were not initially designed to represent workers in collective bargaining arrangements to secure wages and hours. It was first founded in 1869 as a secretive fraternal organization of organized garment cutters in Philadelphia, who were frustrated by the limited vision of their union. While they had grand visions of uniting all of labor under one organization, they grew quite slowly at first: organizing other trades in Philadelphia into their own locals and reaching out to other major industrial centers to start local assemblies. Their secret rituals tapped into a deep-seated fraternal culture in working class communities, but also limited their ability to grow.

What launched the Knights of Labor into a truly consequential organization was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Since 1873, the economy had been in a deep depression, and in July of 1877 many workers had had enough. Strikes and riots broke out on the railroads and tore across several large cities, eventually being put down by federal troops and state militias. While the Knights had not been directly involved, the massive surge of energy and resulting crackdown led them to feel it was necessary to form a more serious organization, and they created a national General Assembly in 1878 before finally going public in 1882.

Unlike the burgeoning craft unions of the time, the Knights of Labor didn’t just organize one specific trade. They allowed membership for everyone apart from bankers, land speculators, lawyers, liquor dealers and gamblers, regardless of their nationality, gender, or race, with the notable exception of Chinese workers. The Knights faced the challenge of organizing people working in drastically changing conditions, as mechanization and concentrated capital was creating a new class of machine operatives that sometimes found themselves in tensions with older generations of artisan craftsmen. With their unique structure, however, the order was able to start with those existing well-organized workers and then use them as a launching pad to bring in new, unorganized workers in droves.

Liberal membership policies allowed for all sorts of new innovations in the ways they organized, but it also led to tensions. Without one clear purpose for the Knights, factions arose around questions of strategy: should they act as a union and bargain with employers for wages and hours, should they lobby local legislature and run candidates for office, or should they form a revolutionary organization to overthrow capitalism? Each of these positions was advocated for by a strong faction within the Order.

After steady growth in the first few years of the 1880s, a few converging situations suddenly shot the Knights from around 100,000 members in 1885 to over 700,000 members in 1886. The economy was emerging from one of the many small recessions that plagued the era, leading workers to try to win back the wages they had lost over the prior few years and fueling demands for the eight-hour day. Because the Knights had established roots in nearly every major city and industry, and because of the shocking victory in summer of 1885 in a strike against Jay Gould, one of the most hated robber barons of the era, they became the vehicle for a new wave of labor militancy.

As workers rushed into the Knights of Labor, they began to organize new industries in new ways: organizing the first locals of domestic workers, white collar workers, artists, and even housewives. They also transformed the conditions in long-running industries like textiles and garments, manufacturing, and the building trades, establishing boards of arbitration and even achieving co-management in the firms where they were strongest.

The transformation went beyond just the workplace. Locals and districts of the Knights of Labor fed a new culture of working-class opposition with opera houses, reading rooms, labor papers, baseball teams, and massive parades and picnics. When elections came about in 1886, they fielded third-party workingmen’s tickets and took over leadership in many towns and cities, even electing two Congressmen.

Unfortunately, the Knights had become overly ambitious, and the grassroots desire for confrontation with employers began to outstripe their ability to win. In early 1886, another large strike against Jay Gould ended in failure, and a wave of strikes on the first May Day were quickly crushed when a bomb was thrown in Haymarket Square, killing several police and leading to a nationwide anarchist scare. While the Knights themselves were not anarchist, and their leaders condemned the attacks, at least one of the defendants was an early member of the Order.

With momentum suddenly on their side, employers launched a massive counter-offensive against the Knights of Labor. Forming massive employer associations to coordinate, they would provoke strikes or simply lock out their workers until they agreed to take wage cuts or sign iron-clad agreements to prevent them from being members of the Knights. At the same time, many of the more traditional trade unionists, who had felt that the Knights were infringing on their territory, launched their own attack, forming the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in December of 1886.

Faced with attacks from both employers and other workers, the Order began to collapse in on itself. Different groups of reformers, radicals, and trade unionists quickly turned on each other, and over the following two years, workers fled the organization due to failed strikes, disillusionment with the decline of the organization, or were expelled in a jurisdictional fight.

After losing nearly three-quarters of their membership by 1890, the Knights did have an interesting afterlife. Though it had lost most of its urban membership, the Order had been successfully organizing farmers and farm laborers, Black and white, in the rural South and West. This put them in a strategically important spot when the newly radicalized Farmers Alliance decided to officially get involved in politics and form the People’s Party. The Knights threw their weight behind the new order in the early 1890s after decades of an official nonpartisan stance.

It wasn’t enough to stop the bleeding. The Knights of Labor ceased to become an effective organization after the Panic of 1893 began and many of their remaining leaders and districts were expelled from the organization, as the remaining membership cratered from over 100,000 to under 30,000. A few core members stayed around for decades, but the national office finally closed in 1917. Despite these failures, the Knights had laid the groundwork for future advancements in the labor movement.

Even as the AFL became the conservative hegemonic force in the late 1800s and early 1900s, former Knights of Labor led the resistance. Eugene Debs’s American Railway Union was inspired by and directly worked with earlier Knights on the railroads. It was former Knights of Labor like Big Bill Haywood, Lucy Parsons, and Mother Jones who helped found the Industrial Workers of the World. When the Congress of Industrial Organizations split off from the AFL in the 1930s, they were led by the United Mine Workers of America, which had gotten its start as a Knights of Labor union.

What Can We Learn From the Knights?

It can seem somewhat absurd to draw any grand sweeping conclusions from a 150-year-old labor organization that only was particularly relevant for a few years in a completely different era of history. However, compared to some more traditionally left-wing touchpoints, it has a few benefits. It actually did organize a diverse swath of the working class, it was able to win over people who were not already ideologically aligned with a left-wing project, and it did so under conditions that were, if anything, worse than the ones we face today. For that reason, its successes and failures should at least be considered.

The first lesson is that a broad working class coalition is an achievable and worthwhile goal. The Knights existed at a time when cultural and racial divisions were much deeper than today, but they still managed to build a culture on top of it that broke down many of these divisions in local communities and across the country, at least for a bit. Even after they declined, these new possibilities and connections laid the groundwork for future organizing.

Second, part of what made the Knights so successful was their ability to face and organize the working class as it was, rather than how it had been. Much as we now think of the prototypical worker as a white man on an assembly line, the labor movement before the Knights was focused on skilled craftsmen who worked with their hands. While they were able to use that group as a starting point, the order was only able to grow once it forged the connections between this older group of labor activists and the new diverse base of machine operatives and common laborers that made up the new working class. Similar lessons could be taken in negotiating between the incumbent labor movement of today and the growing non-traditional working class of the modern economy.

Finally, the Knights show the necessity of a clear purpose for specific organizations. Over the years, the Order tried to be a labor federation, a fraternal organization, a mutual aid group, a lobbying force, and even a political party. It did none of these well, and the arguments over what they should be doing ended up taking more oxygen than trying to do one thing would have. And it didn’t need to be everything to everyone. The Knights were most successful when they were part of a broader ecosystem of working class culture and organization that they could both grow and grow from.

There is so much more to say about this deeply unappreciated and under-studied organization. Facing the prospect of massive reactionary social backlash and the gutting of national labor law, the ability of the Knights to briefly succeed before quickly collapsing deserves more attention from organizers and labor leaders looking to build a broad-based working class movement today.