In April of 1978, Alexander Giacco of Hercules Inc. and Irving Shapiro of DuPont, launched a joint attack. Speaking to a meeting of the Wilmington Rotary Club, Giacco stated that Delaware’s government had gotten too bloated and that income taxes were too high as a result. Two days later, Shapiro, a prominent Democrat, was quoted in the Wall Street Journal saying that he would not recommend that businesses relocate to Delaware given the state’s income taxes on high earners.

When Governor Pete Du Pont later recounted the story in an interview with Larry Nagengast, he recalled the average Democratic representative’s reaction:

Well, what does every Democrat in the legislature think when he reads that? He or she thinks, geez, it’s not Pete du Pont telling me this. It’s a guy who gave me $200 to run, a guy who helped run the Democrat Party. So, it was a good thing.

Within two years, the legislature had slashed the top tax rate and limited their own ability to raise taxes in the future.

After winning re-election, Governor Du Pont called a press conference on January 14th, 1981. For months, he had been negotiating with banks seeking to lessen their regulations by moving to Delaware, and together they had drafted the Financial Center Development Act. The legislation would scrap all caps on interest rates and junk fees, completely transforming our banking industry for the worse, but it would also create a lot of jobs in Wilmington.

There was a catch, though. The banks would only move to Delaware, the governor proclaimed in his press conference, if the legislation was passed by February 4th, just three weeks away. Despite some token opposition, the bill was passed on February 3rd.

In 2025, we are facing a very similar situation. Whipped up now by Elon Musk or Bill Ackman rather than Alexander Giacco or Irving Shapiro, business leaders are threatening to leave Delaware. To keep them here, our elected leadership is working with them to pass legislation that could hurt millions of people across the country, hoping that it might preserve our revenues.

This form of gangster capitalism, where incredibly wealthy people are able to set the demands and force elected leaders to cater to their whims or face destruction, is not unique to Delaware. Across the country, governments are constantly forced to sell out the interests of their constituents to preserve tax revenues and keep jobs in-state. However, there are few places where it has been so ingrained into our governing mythology. By looking at Delaware, where many of these trends are boiled down to their purest form, maybe we can figure out how a different model might be possible.

The Visible Hand of The Market

The stories of Alexander Giacco, Irving Shapiro, Pete Du Pont, and Elon Musk don’t just give examples of how gangster capitalism has shaped the state. These examples all point to an important aspect around how it tends to operate: not in impersonal market trends, but the specific threats of individual companies and leaders.

While Elon Musk had already pulled his companies out of Delaware before the creation of Senate Bill 21, his constant railing against the state’s courts have played a clear role in creating the “DExit” narrative that prompted the legislation. Notably, concerns about a DExit were not found in corporate filings, which officials have confirmed show no evidence of an exodus, but rather from a “market canvas” of individual lawyers and firms.

At the high levels of corporate power, especially in Delaware, this market is very insular and a bit incestuous. Richards, Layton & Finger, which helped draft SB 21 and many other corporate laws, also represented Tesla in the Court of Chancery. Leo Strine and William Chandler, both former members of the court, are now partners at law firms that represent large corporate clients. Even Bryan Townsend, the majority leader and prime sponsor of SB 21, is a corporate lawyer at Morris James LLP. Naturally, given Delaware’s preeminence in corporate law, all of these law firms tend to have close relationships with some of the wealthiest and most influential people in the world.

Insularity is an inevitable part of any institution. It can be found in Delaware’s legislature as well, where individual representatives are much more willing to trust the lobbyists and colleagues they’ve been around for years than advocates or outsiders who seem to appear out of nowhere to make demands. We all have people that we work with, and those relationships are going to have effects on how we act and believe. In the case of economic policy, this often means that those legislators are in closest contact with a tight network of self-interested “experts” who can drown out any outside opposing views.

Where the real problem arises is when this dense network of relationships meets the massive concentration of power and capital. Back in 1981, New York banks were able to make demands of legislators because they really could bring in or take away thousands of jobs. In 2025, the worries about a complete hollowing-out of Delaware’s budget might be overblown, but each large corporate exit would take $250,000 with it from the budget. If the relationships are the carrot of gangster capitalism, the potential of organized capital flight is the stick.

Ultimately, each one of these examples is both a cause and an effect of the broader consolidation of the wealthy elite in the last fifty years. Whenever a wealthy individual or corporation gains a bit of extra money and power, they will use those resources to gain even more money and power. Tax cuts, slashing regulations, and concentrating corporate control all allow a smaller set of people to amass more and more wealth. Concentrated wealth is even easier to get organized, so this allows them to more effectively bully democratic institutions to give them even more of what they want. All you need to do is look at what Elon Musk is doing to the federal government to see where that leads.

A Way Out?

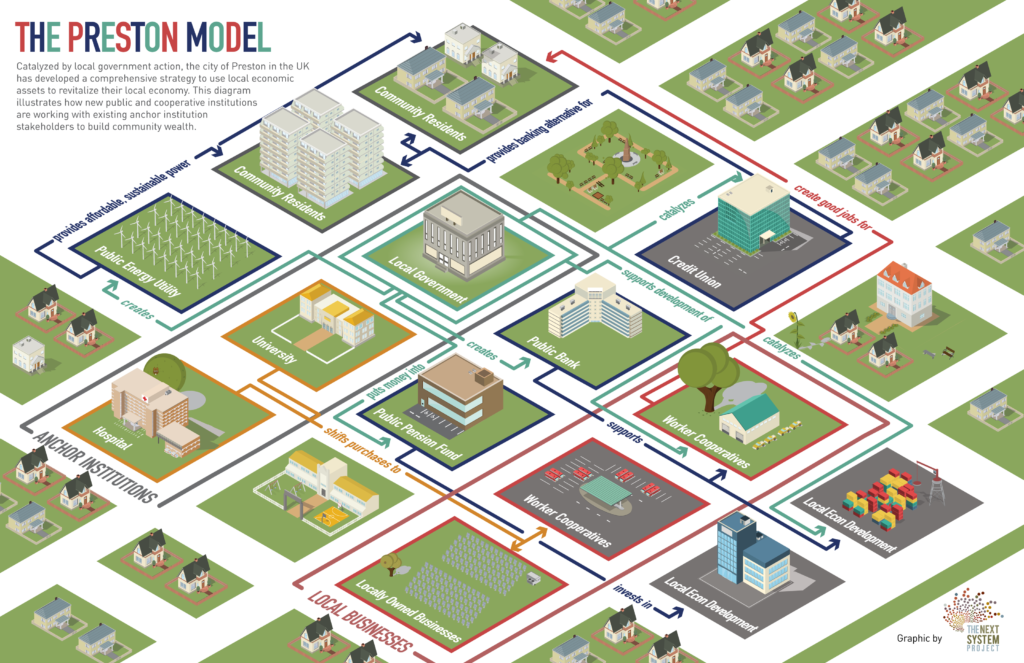

In 2011, the city of Preston in North England was in crisis. The country was reeling from the effects of the Great Recession a few years prior, and now the national government was slashing grants to cities as private investment also dried up. Staring down the barrel of a fiscal crisis, the new Labour government chose to ignore the conventional wisdom of slashing taxes and enticing large corporations with generous public grants. Instead, they began to experiment with a new model of community wealth building.

The new approach combined several different elements: increasing government procurement to focus on local businesses, facilitating the creation of publicly and cooperatively owned local supply chains to fill that demand, and partnering with local anchor institutions to scale up this model beyond just government spending. As a result, more money is being spent within the city, hundreds of jobs have been created, and all of this new local wealth is controlled more democratically than ever before.

This has resulted in projects like Animate Preston, which was funded by the town council and is now a publicly-owned asset creating dozens of jobs and enriching the community. They have also created a cooperative training center that has brought several new worker cooperatives into the community. Other cities across the world have begun to try similar experiments, most notably with Cleveland’s Evergreen Cooperatives.

A lot of the problems that we face from gangster capitalism can’t be solved by any one state. No law that Delaware passes is going to keep billionaires like Elon Musk or corporations like Merck from being able to credibly bully and threaten states who try to impose guardrails on their massive wealth and influence. At the end of the day, the national government needs to step up and tax the wealthy, protect working-class power, and rebuild public wealth. But the Preston example shows that there are some things that can be done for Delaware to chart a less treacherous course through the unforgiving terrain of our second Gilded Age.

We clearly need to diversify our funding sources. As supporters of the corporate franchise love to point out, corporate taxes and filing fees are responsible for a huge portion of our state’s pocketbook. If we want to actually be able to have a democratic say in our economic future, though, we will need to find other ways to raise that money that don’t rely on the exploitation of millions of people across the country and world.

We also need to develop a stronger, more democratic economic base that is not reliant on the whims of big employers and controlling shareholders. That means changing government procurement, but also increasing our state’s public assets rather than just selling them off. It also means promoting the development of local and cooperative businesses that have a vested interest in benefiting the community and their own workers. As the Preston Model shows, there isn’t one silver bullet, but we should encourage dozens or hundreds of experiments in community wealth building that have real resources behind them if we want to have any chance to seize our economic sovereignty back from the billionaire class. The resources are there, we just have to use them.

Time and time again, well-meaning legislators have voted for harmful legislation while wringing their hands about how they wish there was any other way. With national conditions worse than ever, there is no better time to actually discuss how we can build a better, more democratic economy in the first state.

The story of the previous generation of America is how political democracy will always be under threat unless we have some degree of economic democracy. For decades, the concentration of wealth in private hands has limited the ability of our government to actually represent the interests of the public. If we want to fight back against that process in Delaware, we’re going to have to start looking for alternatives to the way things have always been done.