When you set out to learn more about Wilmington’s labor history, most forms of popular education tell a simple story. Whether you are going to a du Pont estate or the historical markers across from the former Bancroft Mills, Delaware labor relations are depicted in a rosy light: employers treated their workers well, and in turn the workers were deeply thankful for the wisdom and kindness of their betters. Anything else was an aberration, caused by malcontents or outsiders.

It is true that Delaware has a much quieter history of labor trouble than many of our neighboring states. We never had anything on the scale of the Great Railroad strike of 1877 or the Homestead Strike of 1892. However, to declare that Wilmington’s workers simply sat on their hands for hundreds of years and never demanded anything is willfully ignorant, if not downright dishonest. In the mid-1880s, the city saw its first major labor movement and a general strike of one of its most profitable industries dominated the news for months. In order to understand how that happened, we need to look at what Wilmington industry looked like in the nineteenth century, before the banks and credit cards arrived, and before DuPont dominated the state.

The Birth of Wilmington Industry

The small outpost that would become Wilmington was first formed by Swedish settlers, but the city as we know it was truly founded in the 1730s when a group of Quakers bought land from Thomas Willing along the banks of the Christiana River and then successfully obtained a municipal charter from King George II (who requested the name be changed from Willington to Wilmington in honor of a friend). Initially meant as a marketplace for surrounding farmers, settlers quickly built mills along the Brandywine which also helped aid the growing docks and shipping along the Christina.1

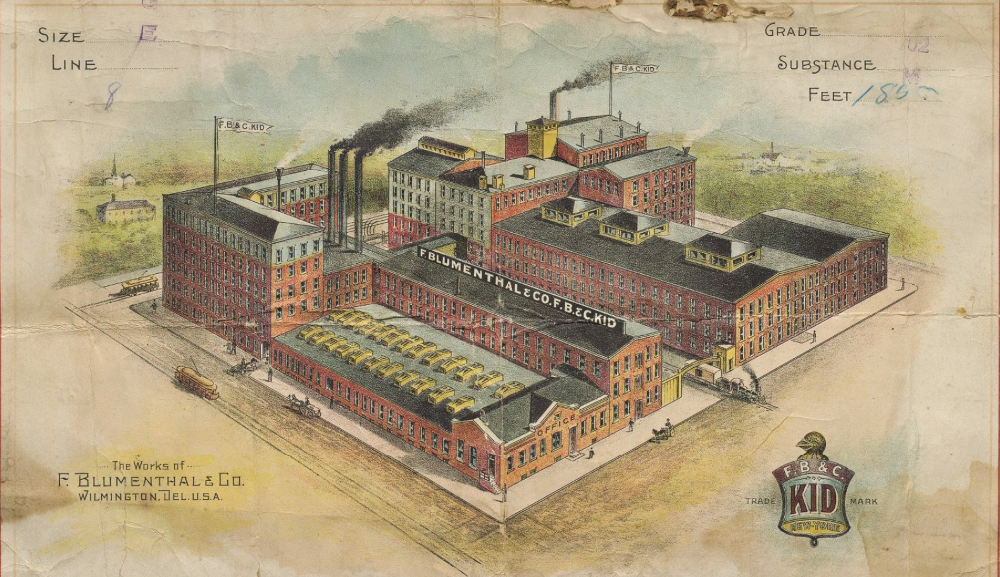

The early residents of Wilmington were mostly Quaker and Scots-Irish, with a limited number of enslaved and free Blacks who had mostly low-paying labor or domestic work. Manufacturing expanded significantly in and around Wilmington in the 1830s and 1840s as new railroads and canals connected cities across the region to Philadelphia, which had grown into the main port between Baltimore and New York City. Railcar production, ship building, carriage-making tanneries, and specifically Morocco leather manufacturing all became major drivers of Wilmington’s economy.2

Factories and steam power grew in the mid-19th century and began a process of consolidation and deskilling that was typical of most major cities. Many of those new jobs were filled by a rising number of Irish and German immigrants.3 However, Wilmington did not see the social unrest that was common in most other east coast industrial cities. Some labor organizations came to Wilmington, often as subsidiaries of larger Philadelphia organizations, but they were rarely controversial and often short-lived.4 Immigrants were mostly involved in skilled work and relatively assimilated compared to other cities, so they often didn’t make much noise. Meanwhile, much of the worst work was done by a relatively isolated Black community that was barred from joining existing trade unions and thus had little way to make demands.5

Additionally, the ruling class of Wilmington was much more integrated into the community than the ruling classes of other cities. Suburbs would not arise until later in the century, so many wealthy residents resided within the limits of a rapidly industrializing city. Discontent with poor utilities had led the city’s prominent citizens to wrest away control of many public goods from the city council and create a commission system that allowed large infrastructure and cultural investments outside the control of city government.6 Businessmen also attempted to adopt a more Quakerly and philanthropic attitude that was able to quickly address labor concerns or stop them before they even began.

All of this gave Wilmington the reputation of a quiet and orderly industrial city with a pliant workforce and low wages. Even before the domination of chemicals, banks, corporations, and credit cards, the foundation of what we might call the Delaware Way was firmly in place. However, as the nation continued to slip into labor unrest, Wilmington would not be able to escape as easily as it had before.

The Knights of Labor

Perhaps the most influential labor organization in the second half of the 1800s was the Knights of Labor. Formed as a secret organization in Philadelphia in 1869, the Knights grew rapidly in the late 1870s and went officially public in 1882. Given its proximity and close ties to Philadelphia, Wilmington actually saw its first Knights assembly in 1873 among shipbuilders and machinists, but the organization didn’t have much influence and only lasted a couple years.7

Unlike other labor organizations in the post-Civil War era, the Knights of Labor didn’t just see themselves as an organization representing the skilled white men in one trade. Instead, they aimed to be a universal brotherhood of all workers: skilled and unskilled, immigrant and native, Black and white, men and women. The Knights were organized into local assemblies, which sometimes contained just one trade, but more often contained members of several different occupations. These local assemblies formed district assemblies, which were all represented in one national General Assembly. Each level elected its own leadership, including names like the Master Workman and the Venerable Sage.8

Local and district assemblies often operated similarly to traditional unions, coordinating and mediating workplace conflicts, but the broader goal of the organization went beyond that. The Knights believed in the creation of a cooperative commonwealth which would allow workers to secure all the fruits of their labor by moving beyond the existing wage system. Their platform called for the abolition of child and contract labor, eight-hour days, equal pay for equal work, and the establishment of cooperative institutions owned by producers themselves.

Many of the Knights’ demands were quite radical for the time, but they were also surprisingly conservative in other ways. Leaders like Terence Podwerly, the Grand Master Workman between 1879 and 1894, despised strikes and radicalism and instead focused on the need for education and arbitration, both of which were also written into the organization’s constitution.9

Despite their official disdain of strikes, the Knights of Labor were defined by them. The organization’s first major period of growth came after the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which brought thousands of members into its assemblies in Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Ohio, West Virginia, Illinois, and Indiana.10 This began the push into a larger, public organization, but it was the Knights victory against the infamous Jay Gould on the Wabash railroads in 1885 that put the Knights into the driver’s seat of the labor movement and set the stage for the greatest year of labor turmoil in American history.

The Knights Come to Wilmington

In July of 1885, the Clerk & Lennox Morrocco Company, which was located in Haverhill, Massachusetts, refused the demands of the local Knights of Labor to fire a foreman who had revealed the secrets of the Knights. Rather than dealing with this local union, Clerk & Lennox decided to move the finishing branch of their operation down to Wilmington, relocating to 744 West Fourth Street (which is now the McDonalds right by the I-95 exit).11

Morocco leather was a particularly soft type of leather which was popular in bookbindings and ladies’ shoes, and by the 1880s Wilmington had become the second largest manufacturer of it in the United States right behind Philadelphia. The industry was in a rapid state of change, as labor-saving machinery was being introduced to both increase output but also to allow the use of less skilled workers. As far back as 1872, a report described a Morocco tannery in Wilmington:

He saw “a bright room where half a dozen pretty sewing machine girls are stitching the wet, slimy skins into bags” while “strong muscular Negroes” fill the bags with sumac dust and water in “gloomy cellars” and upstairs “young Swedes and Irish boys dress the dry skins, a backbreaking operation, apparently,” commented the writer, “in the attitude of laundresses bent over an eternal washboard.”12

This description shows that the workforce of these Morocco tanneries did not match the lily-white, native, male image that is often portrayed of Wilmington’s workers in this era. This workforce would soon be reflected in what would become the largest labor movement the city had ever seen.

Given that Massachusetts was a hotbed of labor activity and Wilmington was generally advertised as having a low-wage, docile workforce and a large existing Morocco tanning labor pool, Clerk & Lennox thought this would be the perfect move. However, labor was on the upswing across the country, and pretty soon the Philadelphia-based District Assembly 94 got in touch with the workers at the new factory and requested that they walk out in solidarity with the Massachusetts workers. Despite their reputation, Wilmington workers complied, with about half the workforce walking out on Saturday, Oct. 3, 1885 and shutting down the factory.13

As the strike went on, both sides negotiated and the Knights began to hold meetings and bring speakers in to rally the troops. They were forming around one assembly a week as of November.14 The strike dragged on for months, and ended somewhat unceremoniously in January of 1886 with both sides reaching an agreement.15 It marked the beginning of a massive organization of Knights in the city of Wilmington, aided by DA 94 in Philadelphia. A Leather Workers’ Assembly was organized in December, and over 100 couples attended their first ball on Dec. 18.

Perhaps the most prominent leader to emerge from this action was Matthew Colwell, an 38-year old Irish immigrant. Contrary to later employer characterizations of strikers as outsiders of unskilled and lazy men, Colwell was a well-established member of the community. He had arrived in the city in the 1850s and became a skilled leather worker who was well-known in the trade. By the time of the strike he was married and was raising two children.16

Over the following months, the Knights continued to organize across all trades from construction to textile manufacturing to printing to railroads.17 According to the evening newspaper, the Knights had around 10,000 members in March of 1886. In 1880, Wilmington had just over 40,000 residents and about 44% of its workforce was engaged in manufacturing work. Given these numbers, it is quite possible that at its peak, the Knights of Labor had organized a solid majority of industrial workers in the city.18

Despite these ballooning numbers, there was not much in the way of labor militancy. While workers began to make demands of their employers, many employers were willing to comply, such as Job Jackson of the Jackson & Sharp car works, who met with his workers, explained his situation, and was able to avoid a strike by promising future wage increases.19

However, not all employers were willing to be so friendly, and pretty soon conditions would deteriorate in the Morocco factories that had caused this whole movement in the first place.

The Wilmington Morocco Strike

Wilmington’s Knights of Labor were riding high in March of 1886. Applications were streaming in from workers across the city, and even from towns as far as Smyrna and Lewes. One of the biggest strongholds of the Wilmington Knights was the Morocco trade, where they had organized 1,500 workers, men and women alike. They had generally been arbitrating without issue and were even looking into opening a cooperative factory to put their unemployed members to work.20

However, the workers were not the only ones who were organizing in the Morocco industry. In response to rising union representation in their industry, employers had formed the Morocco Manufacturers’ Exchange of Wilmington, a subsidiary of the National Morocco Manufacturers Association, to better coordinate responses to potential agitation in their industries. That agitation came quickly.

On the afternoon of Monday, March 22, the Knights sent a messenger to request a meeting with the Morocco Manufacturers’ Exchange the following morning. After receiving no response, as the manufacturers said there was nothing to discuss, the Knights ordered all Morocco workers to walk out. On the morning of Wednesday, March 23, they did. Over 1,500 men, women, and boys, Black and white, gathered at the Institute Hall at Eighth and Market for a quick meeting before filing out. The meeting was chaired by Colwell, who was now the master workman of the Leather Workers’ Assembly, and he discussed the issues that workers had with being paid significantly less for their labor in Wilmington than workers in Philadelphia.21

On March 24, the Manufacturers’ Exchange did finally agree to meet with Colwell and the board of District Assembly 94 to discuss wages. Workers went back to work the following day, but the peace was temporary. Colwell and other District Assembly 94 leaders met with the Manufacturers and presented a new wage scale which had been prepared by the local assemblies, but an agreement could not be reached, as the Wilmington manufacturers claimed they must pay lower wages in order to compete with Philadelphia’s much larger industry.22 One of the strikers explained his frustrations:

The bosses’ statement that they didn’t know what the board wanted to see them for was too thin. They have been holding consultations every day for a week past. They knew this thing was coming and they knew what they were wanted for by the board. The demand is substantially that the men be paid quite or nearly the same wages here that are paid in Philadelphia. This would require a raise of different amounts in the various shops, according to how the rate of wages are paid now. The object is to have the same wages paid in every shop in the city.

At the present time for the same work that we get $1 a dozen for, Philadelphia pays $1.62½; for what we get $1.25 a dozen, they pay $1.75; and where we get $1.50, they pay $2.15. By the week we demand an increase from $1 to $4. Tanners and beamsmen in Philadelphia get from $2 to $3 more per week than we do for the same work here. We see no reason why manufacturers should not pay as much as is given for the same work just 30 miles away.23

The Knights held another mass meeting on Monday, March 29 with over 1,000 workers attending, and on Tuesday workers once again began to walk out across the city. Some stayed behind, but they were eventually booted out by squads of other strikers going factory to factory.24

Over the next several months, the union and the industrialists were locked in a stalemate. A couple of business owners broke off from the Manufacturers’ Exchange and tried to cut separate deals, but given that the Morocco market was sluggish already, most of the manufacturers felt they had no need to negotiate. In late April, the Knights began work on a cooperative Morocco factory just outside the city limits of Wilmington, but it was never finished.25

Within weeks, the employers’ refusal to negotiate began to take its toll. By the beginning of May, national backlash against the Knights was reaching a fever pitch after the failed Great Southwest Strike on the Gould railroads out west and the backlash to the Haymarket bombing in Chicago. This began to take its toll in Wilmington. Matthew Colwell dropped off the radar after May 14, 1886, which is also when strikers began to publicly express frustration with the extension of the strike.26 When a Morocco worker attempted to return to work, he was beaten, prompting outcry by many in the city, though the Knights of Labor denounced it.27 As some striking workers began to seek jobs outside of the state, where wages were already high, the Manufacturers’ Exchange began to hire scabs to replace their jobs, slowly beginning to operate at a lower capacity.

In August, there was finally a meeting between the Manufacturers’ Exchange and Terence Powderly, the national leader of the Knights of Labor, but no agreement was arranged and the strike dragged on. By the beginning of October, strikers had steadily begun returning to work on their own accord, and the strike was officially called off on Monday, Oct. 15 by the executive board of District Assembly 94. Around 300 workers were still holding out, but so many scabs had been hired that people were only able to return to work on a case by case basis, though employers declared they would not discriminate against the strikers.28

Conclusion

In the wake of the strike, the Knights of Labor declined quickly in Wilmington, as they did across the country. They were officially broken in 1890 as factories declared they would fire anyone who was still a Knights of Labor member.29 Matthew Colwell seemed to remain active in the community and eventually changed occupations to work in the local shipyard. He died early on the morning of Feb. 21, 1922 at the age of 74 in his home at 615 W 9th Street.30 Delaware’s labor movement of the following decades mostly avoided the radicalism and violence that marked movements like the Homestead and Pullman strikes, and the American Federation of Labor became the most prominent, moderate voice for labor in Wilmington.

On its face, the strike seems like an abject failure. Employers did not raise wages, the Knights of Labor collapsed in the city, and no substantial labor movement would emerge in the city again for decades. However, the story of even a brief, unsuccessful uprising is an important counter to the prevailing narrative of Delaware’s unique, unbroken line of labor peace and stability.

The Delaware Way is not something that is in our soil — it is contingent on a stable and integrated workforce that does not always exist, and on benevolent and agreeable employers that do not always play ball. It also shows that as Delawareans we are not exempt from the divisions that wrack the rest of the country. From the 1886 strike to the 1968 uprisings to the shaking up of our elected leadership since 2016, we must reckon with economic inequality, racial injustice, and political contradictions that can not always be solved with a handshake and a backslap.

The Wilmington Morocco Strike did not reshape the city in the way that many of its participants hoped that it would. But the story of the strike sends a message to us today that organizing is always possible, even in a state that doesn’t reward it.

Notes

- Wilmington, Delaware: Portrait of an Industrial City, Carol E. Hoffecker, pgs. 18-21.

- Ibid, pgs. 31-39.

- Ibid, pgs. 42-46.

- Ibid, pg. 135.

- Ibid, pgs. 129-136.

- Ibid, pgs. 65-78.

- Guide to the Local Assemblies of the Knights of Labor, Jonathan Garlock

- William C. Birdsall. “The Problem of Structure in the Knights of Labor.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, vol. 6, no. 4, 1953, pp. 532–46.

- Knights of Labor. Constitution of the General Assembly: District Assemblies, And Local Assemblies of the Order of the Knights of Labor of North America. 1883.

- History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol 1, Philip Foner, pg. 506

- Every Evening, Oct. 5, 1885.

- Wilmington, Delaware: Portrait of an Industrial City, Carol E. Hoffecker, pg. 39-47

- Every Evening, Oct. 5, 1885.

- Every Evening, Nov. 1, 1885.

- 1880 United States Federal Census

- Smyrna Times, Jan. 13, 1886.

- Guide to the Local Assemblies of the Knights of Labor, Jonathan Garlock

- Wilmington, Delaware: Portrait of an Industrial City, Carol E. Hoffecker, pg. 44, 142

- Ibid, pg. 143

- The Morning News, Mar. 20, 1886.

- Ibid, Mar. 20, 1886.

- Ibid, Mar. 27, 1886.

- Delaware Gazette and State Journal, Mar. 25, 1886.

- The Morning News, Mar. 31, 1886.

- Delaware Gazette and State Journal, Apr. 22, 1886.

- The Morning News, May. 21, 1886.

- Ibid, May. 28, 1886.

- Ibid, Oct. 18, 1886.

- Every Evening, Nov. 1, 1890.

- Ibid, Feb. 21, 1922.