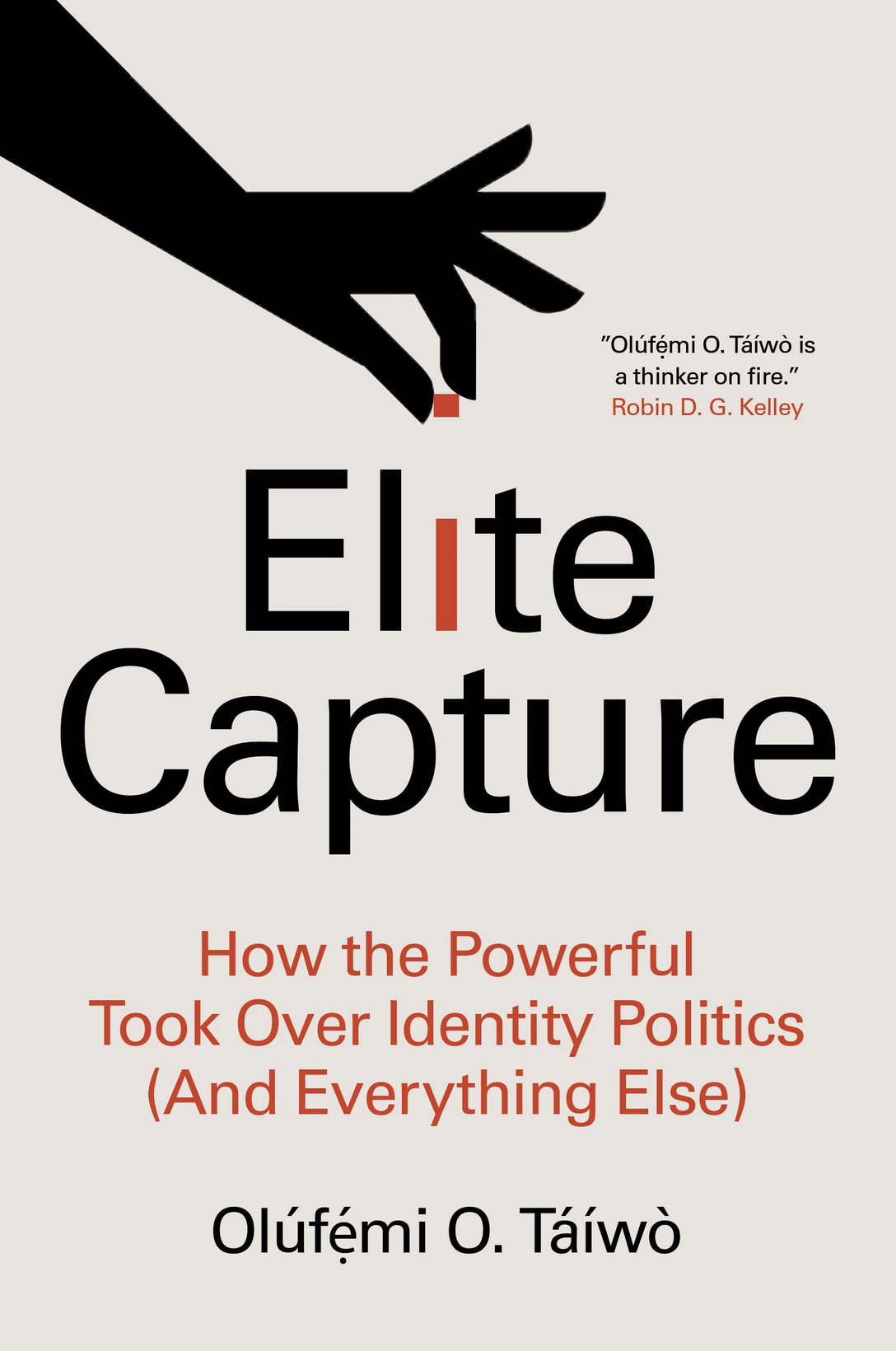

Elite Capture

by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò (Haymarket Books, 2022)

“Building Resilient Organizations”

by Maurice Mitchell (The Forge, Nov. 29, 2022)

While pundits—crypto-fascist to liberal—have decried, bemoaned, patronized, satirized, and slandarized socialism and identity politics, leading left forces have been charting a course of intersectional solidarity and world-building unity. Along the way, they are bolstering the role of the multiracial working class in our struggles and offering an alternative to “neoliberal identity politics.”

Key documents are “Building Resilient Organizations,” by Working Families Party National Director Maurice Mitchell, and Elite Capture, by Democratic Socialists of America philosopher and Georgetown University Professor Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò. Both works came out late last year, Mitchell’s in The Forge, a journal for progressive organizers. Mitchell’s essay focuses on professional relationships among staff in a progressive non-profit. Táíwò uses philosophy and the history of revolutionary movements to suggest an alternative to the elite capture of identity politics: constructive politics, “a world-making project aimed at building and rebuilding actual structures of social connection and movement, not mere critique of the ones we already have.” (84). WFP cites Elite Capture in its study materials for Mitchell’s essay.

I first became aware of these trends when I joined the newly activated Delaware Chapter of DSA in 2021, having been a nominal member of DSA since 2006. In an intake Zoom with the national organization, I was introduced to a key “Community Agreement” for successful discourse: “Call in, don’t call out.”

Ok, so DSA’s not that into call-out culture, I surmised. Good. Having been an autoworker for thirty-one years, a UAW dissident, an elected rep, and Secretary of the Delaware A. Philip Randolph Institute, I was part of a multiracial working-class community who struggled mightily in both shop and street to solve critical issues of safety, discrimination, economic justice, and dignity. Sometimes, while trying to do the right thing, folks said the damnedest things, things that would bring gasps and vapors in the rarified air of academia that I inhabited in my second career.

Most of those years, I was not a leader but just a shop mate, welding steel car bodies next to union sibs and frenemies. My shop-mates flavored their discourse with uninhibited insult, down to the nicknames we imposed on each other: Easy Money, Li’l Bit, Sarge (she was one of the guys), A-rab (a Jew). A diminutive Black trans woman was Sweet Thang. Joe College was going to college. I’d dropped out, so I was Professor—just to remind me I wasn’t—or Red Phil because, you know.

And trauma? Many had endured combat. And the phrase “beat him like a red-headed stepchild” had a special cachet in their biographies. But hungry children from Mississippi, Appalachia, and San Juan were makin’ it in what pioneer UAW president Walter Reuther bragged was a “gold-plated sweatshop.”

And I’d also known the glories and abuses of 60s radical politics, having joined Students for a Democratic Society soon after dropping out of college. Towards the disintegrating end, SDS and other organizations turned malevolently inward, hounding each other in marathon criticism-self-criticism sessions characterized by compulsive smoking, a temporary lift, absurdist positions, emotional breakdowns, burnout, and then flight from engagement. All too often, behind the disruption was COINTELPRO, “a series of covert and illegal projects . . . conducted by the . . . FBI [from 1956 to 1971] aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic American political organizations” (Wikipedia).

In June of last year, Intercept correspondent Ryan Grim published “The Elephant in the Zoom,” along with his Deconstructed podcast “The Implosion of Progressive Organizing.” He reports how in the wake of the George Floyd murder and then the economic opportunities of the new Biden administration, a host of Washington-based progressive non-profits ran aground with staff grievances blended with racial and gender reckoning.

As a counterpoint, Grim introduces Lorretta Ross, who had posited DSA’s “call in, don’t call out” precept. A Black reproductive rights activist of my generation, Ross describes calling in as “calling out with love.” She teaches courses on the topic (“If you need a trigger warning or a safe space, I urge you to drop this class”). She, too, claims the disruptions are reminiscent of COINTELPRO.

That office grievances and identity yield such organizational discord, suggests Ryan Grim in a Feb. 3 Deconstructed podcast, stems in part from a paper by Tema Okun called “White Supremacy Culture.” Composed in the late ’90s, Okun’s paper “claim[s] that basic elements of organizational life—editing, performance reviews, deadlines, urgency, the written word, perfectionism, etc.—are actually all characteristics of white supremacy culture.”

Interviewed by Grim, Okun explains that she did not base her paper on research, but it just came to her after attending several anti-racism workshops. She admits to Grim that her work has been misused as a “checklist to assess or target someone and say . . . you’re colluding with white supremacy culture.” She further allows that she mistakenly included her Black mentor Kenneth Jones as a document co-author, and he later said he did not want his name associated with it. Grim tells Okun that he’s “heard some complaints from people who are black leaders of organizations, who are like: I’m getting hammered by all of these white staffers with this document, written by a white lady.” In response, Okun pleads, “if you are listening to this and are using it in that way, please, please stop.”

Michelle Goldberg weighed in regarding Grim’s grim revelations on December 16 with a beacon of hope: “The Left’s Fever Is Breaking,” in which she specifically cites Maurice Mitchell’s manifesto.

In “Building Resilient Organizations,” Mitchell begins with the problem: leaders and activists in professional social justice institutions are hit with “troubling personal anecdotes that their “spaces are ‘toxic’ or ‘problematic.’” Hence, “[p]eople in leadership are finding their roles untenable.”

Mitchell cites Okun specifically as an animator of such hyper-powered conflict. He parses the topic into causes, symptoms, and solutions.

Causes, writes Mitchell, range from expanded billionaire power to “[e]levation of less representative populations to leadership without institutional support.”

Symptoms fall under several rubrics, such as “Neoliberal Identity” whereby “[m]arginalized identity is deployed as a conveyor of a strategic truth that must simply be accepted, [so that] identity in this context reaffirms the individualistic principles of neoliberalism instead of challenging them.” Other rubrics include “Maximalism,” “Anti-leadership Attitudes,” the “Small War” (“focusing on tensions playing out between junior staff and leadership [or] . . . conflicts between movement formations, sectarian ideological groupings, or movement leaders”), and “Unanchored care” (“Assuming one’s mental, physical, and spiritual health is the responsibility of the organization or collective space.”)

The solution ranges from the unionization of professional staff to strategic issues like clarifying organizational strategy, building “a culture of celebration,” valuing experience, and, rather than bogging down in what he refers to as “postmodernist relativism,” hewing to Marx’s famous thesis: “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.”

Except for WFP, none of the “progressive” non-profits whose discord Michelle Goldberg frets about implies the mobilization of the working class in their mission. With DSA and Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, that is precisely the point.

In Elite Capture, Táíwò uses history and philosophical analysis to make his case for constructivist politics.

According to DSA’s Multiracial Organizing Committee (MROC) study guide to Elite Capture, “the term . . . was used historically to describe the way people with power and advantage tend to gain control over financial benefits meant for everyone. Táíwò expands this definition to refer to how social movements and political projects can be captured by elites who then redirect them toward their own narrow interests.”

Táíwò examines historical cases of elite capture in critiques of the U. S. Black bourgeoisie, the deprecation of Black dignity in the education of Black children, and in Franz Fanon’s critique of African bourgeois, who turned “the all-embracing crystallization of the innermost hopes of the whole people . . . [into]. an empty shell, a crude and fragile travesty of what it might have been” (16).

Táíwò provides a positive case study in the liberation movement of Cape Verde and Guinnea-Bissau, where revolutionaries from educated classes applied the liberatory pedagogy of Paulo Freire to overcome the limitations of their class experiences. Alongside armed struggle, they established schools, recreational facilities, and camps sensitive to religious and cultural practices among the working and peasant classes of the Portuguese colony, engendering a high degree of mass class consciousness.

In the present context, Táíwò identifies elite capture in what he calls “neoliberal identity politics” and its practice of “deference” politics. Accordingly, Táíwò’ excavates the origin of “identity politics” and provides us with the clever notion of “rooms.”

From 1977 to 1980, a group of Black Feminist Lesbians calling themselves the Combahee River Collective held seven retreats to discuss priorities from their lived experience, not merely as white women’s tokens or Black men’s secretaries. They christened their practice “identity politics.” Quoting Princeton Professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Táíwò insists that “the identity politics they developed served as ‘entry points for Black women to engage in politics,’ rather than a whole cloth withdrawal from problematic organizations and movements” (How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 5-6, Táíwò’s emphasis).

Deference politics, explains Táíwò, shows itself in “the call to ‘listen to the most affected’ or ‘center the most marginalized,’ now ubiquitous in many academic and activist circles” (70).

What’s wrong with that, I ask? In the same orientation where I learned to call in, not call out, I learned to use the progressive stack, to move the oppressed and marginalized ahead in line to speak. As a teacher, I learned that we—Black, white, male, female—tend to call those on our left before those on our right (as westerners read), the front row before the back, young men before young women, and whites before non-whites. One need not ascribe unconscious bias to benefit from self-monitoring in this regard and self-correcting. And this is where rooms come in.

A room is simply a space where some things are possible and some not.

For example, consider the room where certain individuals gather to form a political organization, like a chapter of DSA. What are the available opportunities, histories, resources, educational levels, and other affordances or “stuff built into the social environment that we can use to act together”? (Kristie Dotson and Saray Ayal, “Conceptualizing Epistemic Oppression,” Social Epistemology, 2014, in Táíwò, 60). Being in the room implies that we are not necessarily representative of those outside the room. “Listening to the most affected,” argues Táíwò, isn’t “usually because they intended to set up Skype calls to refugee camps or to collaborate with houseless people” (70).

Of course, we are not just talking about yielding a conversation to someone with little to say. “The politics of deference focuses on the consequences that are likeliest to show up in the rooms where elites do most of their interacting” (73). Unfortunately, warns Táíwò, “the more we focus on changing our norms of interactions to ones that locally and cosmetically elevate the voices and perspectives in the room, the harder it becomes to change the world outside the room” (82-3).

Maurice Mitchell addresses what exacerbates the discord inherent in deference politics, social media: “The profligate and unexamined use of social media has amplified this particular trend. These platforms—owned and controlled by megacorporations—reward us for our ability to articulate or reshare the sharpest, pithiest, pettiest, most polemic, or most engaging ‘content.’ There is no premium on nuance, accuracy, and context. There is little room for low-ego information sharing or curious and grounded political education. These platforms are ideal for, and give immediate reward to, uninformed cherry-picking, self-aggrandizement, competition, and conflict.” I would add there is little due process, either.

Elites not only capture our internal discourse. Media and lobbies like AIPAC silence working-class, left, and pro-Palestinian voices from the outside. Why help them?

Elite Capture has its detractors. Pascal Robert, co-host along with Jason Myles, of This Is Revolution podcast, slams Elite Capture as “vapid rad-lib pablum,” basically for not going far enough. First, he questions whether the Combahee River Collective was even a movement significant enough to be foundational of anything, much less “identity politics.” Second, Táíwò does not emphasize enough how non-profits were created to elevate a buffer class of elites over radical working-class voices. (Pascal interrupts himself to say he’s not suggesting some George Soros conspiracy.) And finally, he condemns Táíwò for receiving a grant.

Well, Combahee never pretended to be a movement. It was an “entry point” (see above) for its members’ participation in coalitional activities. As for giving those nefarious non-profits a pass, the book was about revolutionary movements, not non-profits. (Gee, Maurice Mitchell won a Soros Foundation Justice Rising Award. Don’t tell Pascal). As for Táíwò’s grant, he’s a prof, and profs get grants. And using a grant to open rooms for a class-conscious working class is a great way to expropriate the expropriators (thanks, Marx). As for Táíwò being a professor, Pascal bloviates, “Academics are the enemies of the people!” O-kay.

All this reminds me of some instructive concepts from Mao Zedong’s “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People.” While Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution made a mockery of the work, it gave us two useful terms. Antagonistic contradictions were those between the people and the enemy, be they Japanese invaders or capitalists, and they could only be resolved with force. Non-antagonistic contradictions were those among the people, meaning workers and their national allies, and they could be resolved through persuasion. “When we fight,” sings Billy Bragg it in his version of The Internationale, it’s only when “provoked by their aggression” and “inspired by life and love.”

Unity of the people is how we constrict the power of capitalists to fund politicians like Ron DeSantis that protect their profits by scapegoating Black people and queer folks in one comingled frightfulness: “This course on Black history, what [is] one of the lessons about? Queer theory.”

Workers are on the move, and we need to be ready to stand with them. DSA’s Multiracial Organizing Committee is bent on recruiting them as their response to Elite Capture and the call for constructive politics. Right here in Delaware we have eight Amazon facilities and scores of Starbucks stores, whose workers have launched historic union drives nationwide. Southern Delaware is home to thousands of immigrant poultry and agricultural workers, compelled to work cheek by jowl during the pandemic as essential but not valued workers.

My union, the United Automobile Workers, has just elected five members of a progressive reform slate, UAW Members United, to its International Executive Board after the old guard took bribes for two-tier wage contracts and fourteen of them were convicted of corruption. Two spots are in a runoff to get a majority, including the international president. Several members of Members United that I phone banked with were DSA comrades. This year, the Big Three contracts expire, and we may see the most consequential strike in half a century, if not a possible Teamster strike at UPS.

It’s no secret that today’s Easy Money, Li’l Bit, and Sarge are disaffected by neoliberalism, but they need a better alternative to the politics of Fox News-style resentment than our dysfunctional call-out culture.

Now, I am speaking for myself, not for any of my comrades. I don’t expect anyone to buy into this call for constructive politics without frank and unhindered conversations. I wrote this with love for those working for a more just Delaware and world but with a little fear of them, too. So please don’t call me out if you are troubled by these ideas. Call me in and we can talk. You’ll get my number if you hit me up at pbannows [at] gmail [dot] com.

Phillip Bannowsky is a poet and a retired auto worker and educator. He is currently Co-Chair of Delaware Democratic Socialists of America.