It is 6:30am on a cold Friday morning in January. I am preparing to attempt to log onto my school district’s online portal. It is a futile effort – nearly all of the 21,000 teachers in my union have been locked out by our city’s mayor, after the union voted to work remotely until the district agrees to our demands for stronger Covid safety measures. But I will still make the attempt, take a screenshot for evidence, and then work on materials for my 11th grade Civics class, until it’s time for a Google Meet with my coworkers at 7:30am.

I am a high school Social Studies teacher in Chicago Public Schools. This time last year, I was a teacher in the Colonial School District in New Castle County. I moved to Chicago in March. When I got here, I found a city and a school district that are not unlike what I knew living in Wilmington.

Chicago gets a bad rap for being a city plagued by violence. Wilmington does, too. And like Wilmington, Chicago’s reputation isn’t very fair. Politicians and the media tend to zero in on the gun violence, but in both cities, those conversations ignore the realities of the people who live there. Both cities are home to a predominantly Black and Brown working class population. Both cities have painful histories of racial injustice. And both cities live in the shadow of a powerful corporate hegemony that heavily influences local politics – often to the detriment of everything else. Despite all of that, in both Wilmington and Chicago I experienced communities of people who have a fearless love and a defiant joy that is rarely captured in evening news headlines.

But Chicago has one thing that Wilmington doesn’t: the Chicago Teachers Union.

It is 7:30am. Time to sign into the Google Meet. There is a weird sound in the background of our union rep’s video. Everyone is laughing and trying to figure out the source. She mutes her mic and we begin the meeting. Today’s topics are our union-wide meeting last night, our thoughts on the bargaining progress made so far, and how to set up a solidarity fund to support members who are struggling with losing pay during the lockout. Everyone seems to be in good spirits. At 7:45am we end the meeting and it’s time to get to work, doing whatever tasks we can without access to the district’s online system.

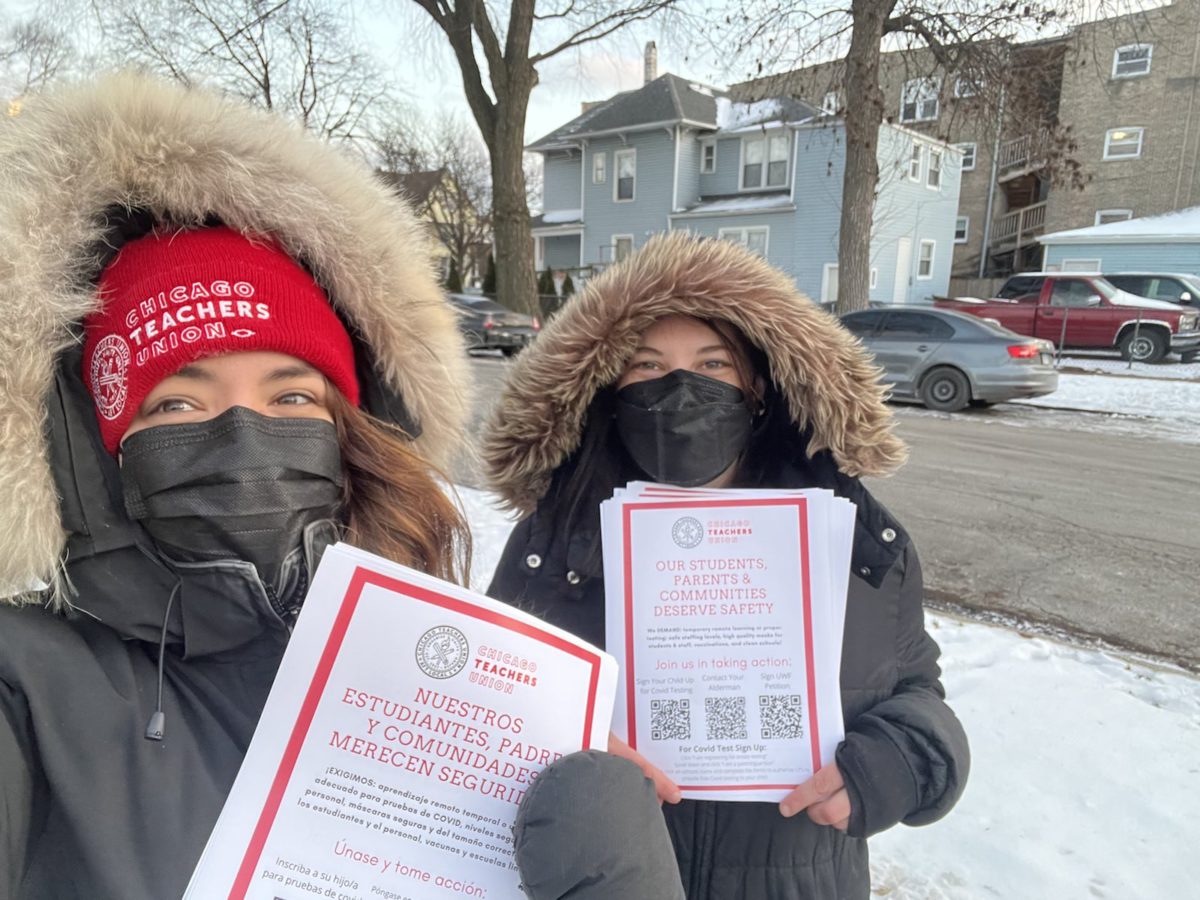

When CTU voted on the remote-work action on Wednesday January 5th, I was nervous. But my anxiety was outmatched by a deep sense of purpose, and a desire to fight for what I know in my heart is right. This is the first union action I have ever participated in, and I am filled with gratitude over belonging to a union that has some teeth.

Today, as I sit here writing a lesson on the Connecticut Compromise, my mind is wandering back to Delaware. I am remembering what this fight for school safety was like when I worked in Colonial School District, how alone I felt, and how different it could have been.

When the pandemic first reached the US, I was nearing the end of my Master of Arts in Teaching program at Relay Graduate School of Education. I tend to think of myself as someone who is highly engaged in politics. I helped organize the Wilmington chapter of Food Not Bombs, I attended city council and school board meetings, and I was involved with Network Delaware. But completing a Master’s degree while teaching full time had overwhelmed me, and I had not been paying much attention to the news. So, when we were told school would be moving online for two weeks, I really believed it would only be two weeks. I went into my school and met with my team. We divided up the lessons we would create. We had just started our Economics unit. I made a Google Earth tour following the episode of NPR’s Planet Money on how a t-shirt is made. Nobody wore a mask or socially distanced. I still can’t believe how naive I was, or that I didn’t catch Covid.

Two weeks stretched to the remainder of the school year. Teachers were allowed back in our buildings to gather our things. I went to my classroom, and found all of the furniture pushed to the side, my personal items stacked haphazardly on my desk. The ceramic elephant lamp I had purchased to try and soften the lighting in the room had been shattered. I thought about all the students I likely wouldn’t see again, and about the last day I had been in this room with them, how scared they all were. One boy had said he wasn’t worried so much for himself, but he lived with his grandparents and he was afraid for them. I sobbed while I packed my things into boxes.

I became depressed and anxious. Trying to teach students online who had completely given up on school for the year, while also attending my own virtual classes and completing my master’s thesis, felt impossible. My partner, laid off from his job at Brew Haha, took over our household chores and our responsibilities with Food Not Bombs. He made me coffee and got me out of bed every morning. When school ended in the afternoon, we went for long walks with our dog on the hiking trails at Alapocas, to keep cabin fever at bay. In the evenings, I worked on my grad school assignments and planned lessons for my students.

When summer break arrived, it did not bring relief. The pandemic had only gotten worse, and with the waves of Covid cases came political unrest. State and local governments, along with right-wing supporters of Donald Trump, clashed with activists who called for pandemic relief and an end to police violence. Food Not Bombs was working overtime, trying our best to fill in the massive gaps left by Delaware’s pandemic response.

Wilmington PD were not happy with us. Our small group of rabble-rousers had tripled in size, and people in the community were starting to pay attention to us. We had been active in supporting people targeted by police violence for years, but now public scrutiny on the Police Department and Attorney General’s office had increased. People were angry. There were weekly protests calling out by name those officers who had killed community members. At one protest, I got into a shouting match with Chief Robert Tracy (who is himself another connection between Wilmington and Chicago, having left the Chicago Police Department in the wake of the coverup of CPD’s killing of Lacquan McDonald). He alluded to protesters in other cities being hit by cars. I called him a pig. I stand by that statement.

Food Not Bombs organized a rally in Rodney Square, calling on Governor Carney to provide financial relief to struggling families, suspend rent payments and evictions, and keep schools and businesses closed. Wilmington PD and Mayor Purzycki’s office contacted Colonial School District, and claimed I had made posts on Facebook threatening violence. I received a disciplinary letter in my file, so I filed a grievance with the union. The letter was removed, but my trust in my principal and CSD administration was shattered.

My relationships with my coworkers were similarly damaged. Many of them did not believe that Covid-19 was as serious as I did. The two teachers I was closest to in my building had been doing some of their own “research.” They sent me materials that reeked of Q-Anon rhetoric. They told me the “Plandemic” was a conspiracy by the government. I tried to reason with them, but they would not be moved. I stopped talking to them.

Summer 2020 ended, and school resumed online. I was relieved, and for a brief moment, I thought maybe Governor Carney and Colonial School District were actually going to do what was needed to keep teachers and students safe. That fall semester, I worked harder than I ever had as a teacher. I often spent 12 hours a day at my computer, teaching classes, meeting with students and parents during my lunch and planning periods, creating videos for students who missed the online sessions, talking on the phone and helping parents navigate Schoology (an online learning platform where teachers post materials for students), and giving every student detailed feedback on their assignments to try and make up for the fact that we couldn’t be in a classroom together.

When Delaware announced that vaccines would be available, I thought I would be able to get vaccinated before returning to the classroom. I was wrong.

In-person learning resumed in February 2021. We returned to our school buildings and to a new atmosphere of anxious, forced cheerfulness. I was terrified, and I kept tearing up in our online staff meetings and having to turn off my camera. In class, I struggled to maintain my composure as I stood in a room with 25 students, many of whom needed constant reminding to keep their masks on over their noses.

I attended meetings with our school’s safety committee. I questioned the plans for covid-mitigation. How could we space students 6 feet apart? And what difference would it even make, with an airborne virus and students unmasking for breakfast and lunch every day? How many positive cases would require a switch to remote learning? How could we possibly have an accurate picture of covid spread in schools, with no surveillance testing, and a contact tracing model that assumed both 100% compliance to masking and social distancing, and that these strategies were sufficient to prevent transmission? What was our plan for students and staff who did get sick, who had long-term effects, or who lost family members? My questions were dismissed. My colleagues insisted that the virus was less of a concern than the learning loss that came from remote learning. A few agreed with me, but quietly. In one meeting, another teacher asked “Why don’t we go on strike?” She was ignored.

My union rep reached out to me, and suggested that I stop attending the safety committee meetings.

Frustrated, I reached out to my school nurse. Surely he would hear what I had to say. He was a medical professional, and he had also just been elected as our building’s alternate union rep. I explained my concerns about the contact tracing model, and pointed out flaws in the studies the CDC had cited when creating its guidance. I asked if there was any accounting for students who were not following masking and distancing protocols. The nurse told me that the expectation was that they would adhere to the guidance. I asked, what if they don’t? He told me to work on my classroom management.

The next day, I received an email from the district’s head of health and wellness, saying that the nurse had told him I had questions about our safety plan. I was shocked. I had not expected him to contact administration, without my knowledge, and call me out by name for questioning the district’s decisions.

I decided that day that it was no longer worth it to remain in CSD. My partner had been missing home, and wanted to live closer to his mother. I was exhausted by CSD’s ineffectual handling of Covid, and by my union’s unwillingness to stand up for its members. I applied for a job teaching in Chicago, and received an offer a few days later. I put in my notice at CSD. Only one of my colleagues reached out, but I received supportive messages from many of my students and their families. We packed up our belongings and headed for Chicago.

And here I am now, in a city that is very like Wilmington, but that is also worlds apart. I can’t help thinking about how many of my fears turned out to be true: that Covid was spreading in schools, that it could seriously affect children, and that we couldn’t be sure our plans were working without surveillance testing. I am tempted to say “I told you so,” but I know those words never help anyone. Instead, I want to reflect on what could have been different, and what can still be done.

I am also remembering the teacher who asked why we don’t go on strike. The simple answer is that it’s illegal for public employees in Delaware to strike, and that the collective bargaining agreement with CSD forbids it. But the real answer – the one many don’t want to hear – is that the Delaware State Education Association, and its chapter in Colonial School District, is shy about taking risks. Their “interest-based decision making” approach insists on avoiding confrontation with the school district administration, often to the detriment of the union’s power. The union leadership fails to understand that the relationship between employer and employee is inherently one of conflict. The employer wants as much from the employee as they can get, for as little cost as possible. That isn’t a moral judgment. That is just a basic fact of capitalism.

A strike wouldn’t have been necessary to fight for our students. There are many direct actions that teachers can take to advocate for better conditions. CTU is an example – by simply insisting on working from home, we have forced Chicago Public Schools to negotiate with us, and we didn’t have to go on strike to do it. Even a less drastic approach might win some big concessions for teachers and students. A work to rule action – where workers only fulfill the minimum requirements of their contracts – would bring a school district like Colonial, which relies heavily on the unpaid overtime hours of teachers, to its knees.

There is power in a union; all it takes is solidarity. We can keep ourselves safe by standing together, remaining firm in our convictions, and refusing to accept unfair and unsafe practices.

And so, I will leave you with the words of the legendary Chicago activist Fred Hampton: “Peace to you – if you’re willing to fight for it.”