Will converting chicken waste into energy be good for Delaware’s environment? It depends on whom you ask, or more to the point, what exactly you mean when you say “good for the environment.”

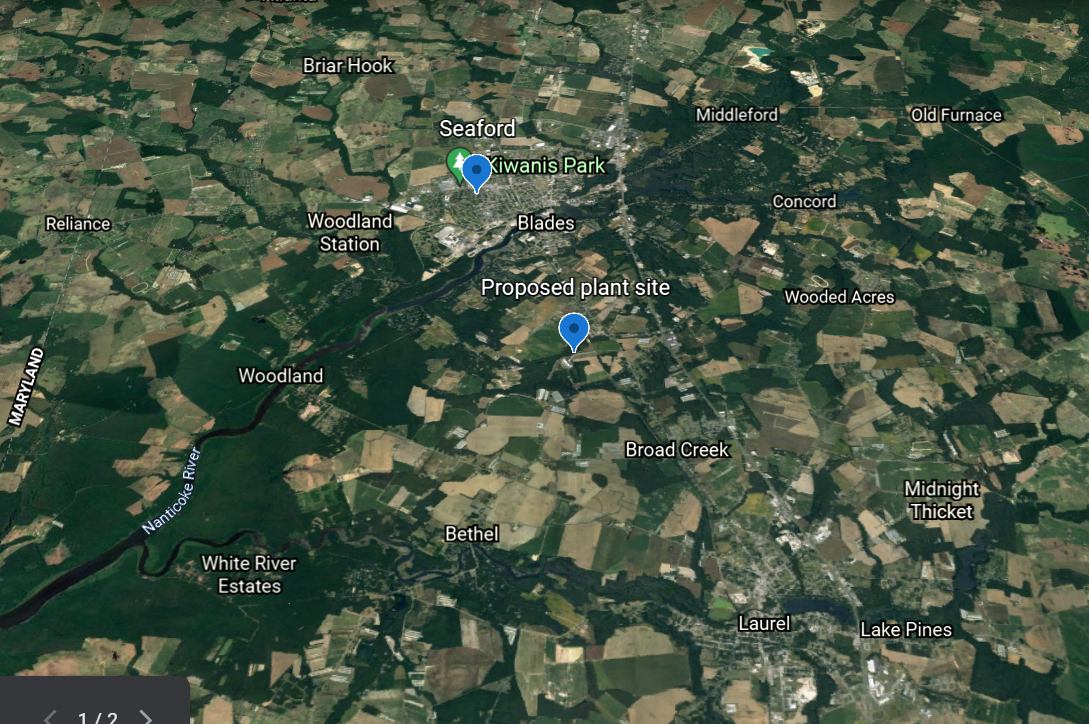

Bioenergy DevCo’s plan to build a $60 million plant near Seaford received zoning approval from Sussex County Council in April. The plant will take chicken manure and excess parts from Perdue Farms, convert them to methane — the primary ingredient in natural gas — using a process called anaerobic digestion, then sell the gas to Maryland’s Chesapeake Utilities.

Groups focused on cleaning Sussex County’s rivers and watersheds favor the project, which should reduce polluting runoff from manure spread on farm fields.

Other groups, opposed to factory farming and concerned about the plant’s health impact on nearby residents, are still trying to block the project, which needs permits from Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control before it can operate.

Both sides claim science supports their positions. Where you stand on the issue probably depends on which groups you trust and which environmental goals you support.

Are you satisfied with a world in which factory farms slaughter millions of chickens, a new supply of natural gas for 5,000 homes is created, and southern Delaware’s bays and rivers are cleaner? Or do you want a world in which factory farming and gas burning are reduced, not accommodated? This plant forces you to choose.

It doesn’t force you to put realism aside, however. How likely do you think it is that we get rid of factory farming, also known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs? They’re the primary way meat, cheese and eggs are produced in the U.S. If you think getting rid of them is not very likely, maybe you take the cleaner water instead.

And maybe you take the money, too. Friends of the Nanticoke River, a group that supports the Bioenergy DevCo plant, is a member of Nanticoke Watershed Alliance, which has received funding from Perdue Farms. Perdue, which will sell its chicken waste to Bioenergy DevCo and which sold the land on which the new plant will sit, clearly has an interest in seeing the plant come online.

Of course, all environmental groups have to get funding from somewhere, and if you’re in an area where poultry farming is both a big employer and one of the main contributors to water pollution, partnering with the industry to help mitigate runoff can lead to cleaner waterways.

“As the director of a nonprofit and an environmentalist, when you have such an uphill battle to clean up the environment, you take the money, you take the support,” said Chris Bason, executive director of the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays, which favors the plant with caveats.

In working to clean up the bays of Sussex County, “We try to involve as many stakeholders as possible,” Bason said. “Agriculture is one of those stakeholders.”

The Center for Inland Bays, which has received funding from Perdue Farms, has requested that DNREC provide “an extraordinary level of oversight” of the biogas plant, given its location near Gum Branch, a tributary of the Nanticoke River.

Other environmental groups say the times we are living in demand radical action, that climate change is too far along to further entrench a polluting industry by creating a market for the industry’s waste from three states.

“We just quite frankly don’t have the time to waste anymore for this kind of nonsense that they expect our kids and grandkids to live with on this planet,” says Maria Payan of Sussex Health and Environmental Network, who is working to block the plant.

If you’d like to tell Gov. Carney to block the Bioenergy DevCo project, you can click this handy link provided by Food & Water Watch.

On the other hand, if you think the project ought to get the state permits it needs, you probably needn’t do anything.

That’s because state law doesn’t give DNREC grounds to deny the permits as long as the plant meets federal environmental standards, says Dustyn Thompson of Sierra Club’s Delaware chapter.

Thompson and others are working with state Rep. Larry Lambert (D-Claymont) on a proposal for a “cumulative health impacts” law that would allow DNREC to take into account existing environmental degradation and the vulnerability of nearby residents in places where new plants are proposed.

In a three-mile radius around the Bioenergy DevCo plant site, which today houses a composting facility formerly owned by Perdue Farms, “people are about three times the Sussex County average to be living in poverty. They are also about twice the Sussex County average to be people of color,” says Greg Layton of Food & Water Watch, citing data from the U.S. Census and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Residents of a mobile home park near the site are mainly Spanish-speaking Latinos, says Layton.

The plant would also bring at least 15,000 heavy truck trips per year to haul waste in, and thousands more to haul gas out, he says. Moreover, not all the waste will be converted to gas. The process will also produce digestate that could end up on local farm fields, leading to runoff, he says.