In the last five years, the left has re-emerged as a force in American electoral politics. From the rise of Bernie Sanders and the Squad to the spate of DSA and WFP victories in state and local elections across the country, progressives and socialists have shown that they can translate their values into electoral wins. But those wins only go so far. In the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, Bernie Sanders still lost to the more moderate Joe Biden, and in Congress, progressives still find themselves without the votes to wield real power.

It is hard to understand the limited success of the left without understanding its limited reach beyond urban cores and college campuses. These areas have served as a base for many of the biggest wins over the last few years, but they are far from a majority coalition. If you want to get a majority, you are going to have to look to the suburbs. Over half of all Americans now live in suburban areas, which are growing faster than either cities or rural areas. This is an important trend for many reasons, but it has proven particularly potent in Democratic politics. As their fortunes have declined in rural areas and Rust Belt cities, Democrats have tried to leverage these growing suburbs to their advantage, as Chuck Schumer infamously explained in 2016.

As these suburbs became a more important part of the Democratic base, they also became an important bulwark against the left flank of the party. It was the suburbs that delivered a House majority to the Democrats in 2018, but it was also this massive increase in suburban voters that delivered 10 of 15 states to Joe Biden on Super Tuesday. Since the election, many of these suburban Democrats have been openly hostile to the activist left, blaming social movements for their underperformance in more conservative districts.

Under current circumstances, it seems inevitable that this trend is just an inescapable part of suburban politics. After all, the suburbs are whiter, richer, and older than the rest of the country. That is not exactly fertile demographic ground for progressive politics, which has thrived among a younger and more diverse working class. But those characteristics are not absolute, and they are not constant.

Across the country, the suburbs are being transformed, becoming less white and less wealthy at rates faster than either cities or rural areas. I have written about suburban poverty before, but the trends go beyond that. Even places that are not necessarily being impoverished are seeing massive demographic changes. It is not happening everywhere, and it is not happening evenly, but it is happening.

For an example, you can look at the garden apartments of East Cobb in the Atlanta suburbs. They are representative of a type of suburb that is becoming more and more common. Built in the 60s, 70s, and 80s during a process of extended white flight, they now cater to a young, diverse working-class crowd looking for cheaper rents outside of the cities. These apartments are not the only places that break the stereotype of a middle-aged, middle-class white suburbia. Instead, they are part of a trend of townhouses, manufactured homes, and small single-family rentals that are on the forefront of suburban diversification across the country. When a change of this magnitude happens, it opens up the opportunity for political change.

At this point, it probably makes sense for me to introduce myself. In 2020, I was the campaign manager for Madinah Wilson-Anton, a progressive black Muslim woman who ran for the state representative in Delaware and won as a part of a larger wave of progressive victories in our primary last year.

The question of how progressives win in the suburbs is particularly important to me because Delaware is a predominately suburban state. Our largest city is Wilmington, which contains just seventy thousand of our overall population of around one million. Apart from some rural areas further downstate, most of our population lives in some form of suburb, and that is where all of our election victories took place this past cycle.

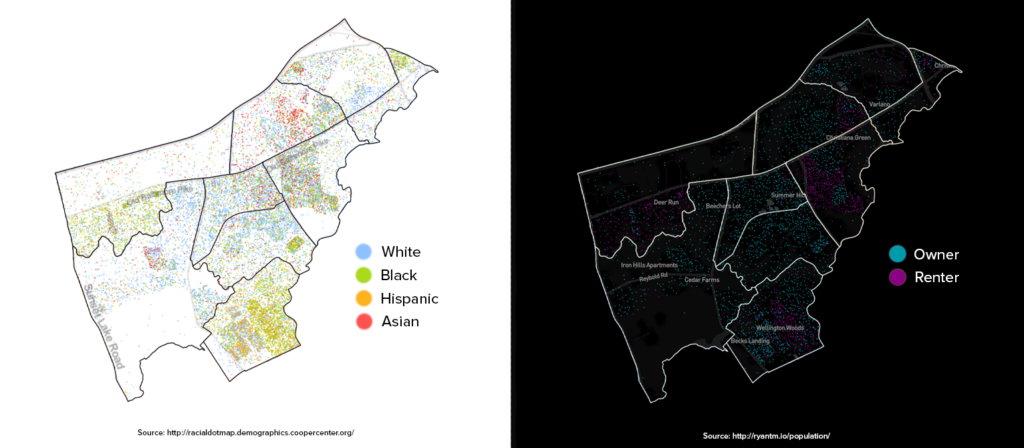

Many of the districts that saw progressive victories looked something like Madinah’s. The 26th House District in is one of the most diverse in the Delaware. It is about 40 percent white and 28 percent Black, with a substantial Hispanic and Asian population that gives it the highest foreign-born population in the state. About 40 percent of residents are renters, a population that is largely made up of young adults.

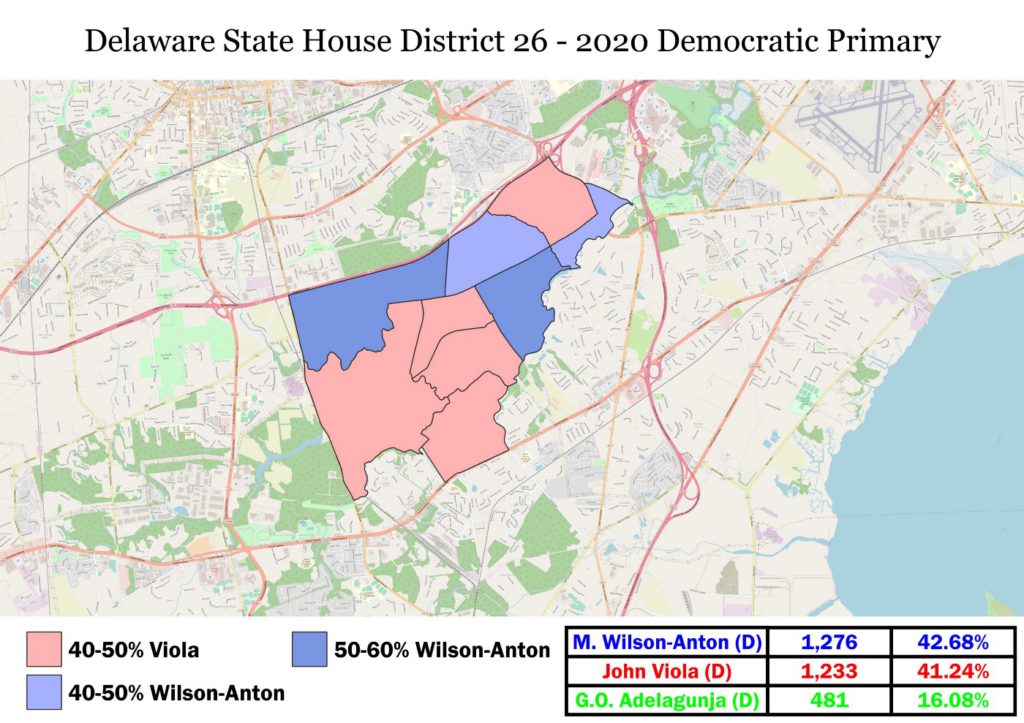

While Madinah only won by 43 votes in the primary, she cleaned up in the areas that had lots of renters and a higher percentages of Black and Asian voters. A similar pattern was seen in the election of Marie Pinkney and Larry Lambert. As progressive black candidates challenging moderate white incumbents, they largely did well in areas with more renters and black voters. Even Sherae’a Moore, running in an open primary below the canal as the most progressive choice, followed these same trends.

If these victories highlight the possibilities of progressive wins in the suburbs, the difficulties we faced during the election highlight the challenges we will have to overcome if there is going to be any chance of winning larger victories down the line.

Perhaps the most pervasive problem we faced on the campaign trail was that of low engagement and low registration. Before the 2020 election, the 26th district had an absurdly low turnout rate in primary elections, maxing out at just 19.6 percent in 2018. Part of this was the lack of any options in past elections, but another part was a consequence of the types of voters that live in the district. There were plenty of long-term residents, but there were also lots of young families who had moved into the district looking for a safe and affordable option outside of the city.

Many of these voters, young adults in their 20s and 30s or immigrant families where only the children could vote, had not bothered to update their registration or did so simply to vote in a presidential election. It was common to see five or more registered voters at one address, with none of them being the person who actually lived there. Even if they were the right person, they usually had never had their door knocked before and had essentially no connection to local politics.

Our tactic was initially very simple: talk to as many people as possible, even if they had never voted before. Before the pandemic interrupted our canvassing operation, we had knocked on every Democratic door in the district at least once, as well as a good portion of Independent doors. When Coronavirus forced us inside, we continued our phone and text outreach to a wide swath of voters, offering whatever aid we could on top of our voter contact.

While the margin was narrow, the strategy seemed to work. 56 percent of our identified supporters had never voted in a primary before, and 16 percent had never voted in a general election. When the votes came in, we had increased turnout by over 60 percent from 2018, and we were able to confirm that many of the new people we had talked to actually did end up voting.

While Delaware’s example is somewhat limited, I hope that it can prove two things: (1) there are new voters out there in the suburbs that are receptive to progressive campaigns, and (2) they will vote for us if we ask them to. There are a variety of tactics that we did not have the chance to try, from simple things like voter registration drives to more targeted community outreach like that done by Sri Kulkarni in Texas (his other politics aside). I am sure that there are also plenty of smaller progressive victories like ours across the country that I have not yet heard of.

Hopefully these smaller victories can serve as models for a broader progressive strategy in the suburbs. The number of these new suburban voters and the ability of campaigns to reach them will vary widely based on the location and the size of the race, not to mention the quality of the candidate. But if progressives want to start building for bigger victories, these are going to be the type of voters we need to bring into our base.