[Editor’s note: The following two poems are excerpted with the author’s permission from Jacobo, the Turko; a novel in verses, by Phillip Bannowsky. You can learn more about Phillip in the About the Author bio below.

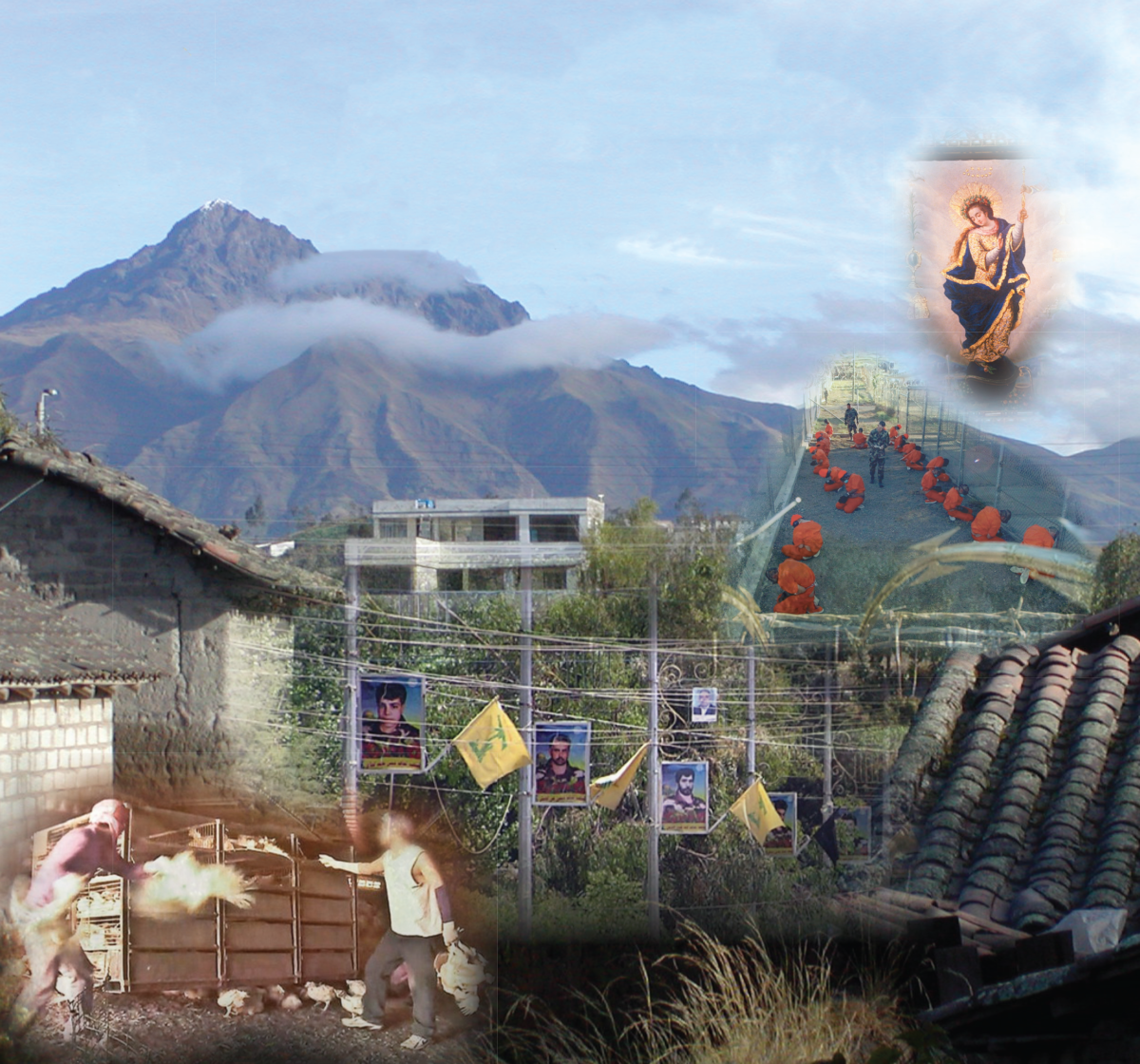

The narrative is told experimentally through a series of miscellaneous ephemera and verses. The protagonist, Jacobo Bitar, is an Ecuadorian man of Lebanonese descent who travels to Rehoboth Beach, Delaware on a J-1 Visa in hopes of restaurant work for the summer tourist season. He ends up working on a chicken processing line in Sussex County. Jacobo is deported by ICE to Lebanon (where he’s never lived). He is eventually captured by U.S. Forces in the Middle East and is sent first to Bagram AFB, Afghanistan, and then Guantanamo Bay Prison, Cuba.

More information about the book, its creator and how you can buy it (not at Amazon) can be found here.]

Jacobo, Not Home Now, Meets Leila

(Previously published in Meat for Tea: the Valley Review.)

If you lived here

You would be home now

—sign entering Bridgeville, Delaware.

She lived with Uncle Pops,

related to him by some skein of obligation:

kinship, chance, desperation.

Theirs was an orphan street discontinued

beyond their one block

by a century of municipal inattention,

which pleased Uncle Pops,

for here was where quote don’t too many people know your business,

his business being marijuana and painting pictures

from his third-floor studio of neighbors

changing tires, tending gardens, or

homesteading behind plywood

and balloons of graffiti:

Snitches get stitches.

I’d spent the day of my rescue showing Uncle Pops

how I could hack marijuana with a machete

and then we’d driven

to Bridgeville where he showed me

that sign and laughed:

If you lived here

You would be home now.

I thought he meant to dump me

but he drove on, and the farther we drove north,

and the more Uncle Pops lectured on towns that memorialized

old world cities, a rejected king, a martyred president,

and settlers who stole

their homes from the Lenni-Lenape,

the more I felt Uncle Pop’s wheels spin me into his skein.

Then I met Leila, who made me feel the tug

of a terrifying attraction,

too far to fly the spark of satisfaction;

As once on high Imbabura,

trekking a path I thought was homeward,

with anticipation rushing me onward as I rounded

an enormous stone, but came upon a cliff edge,

with my village far below,

a tiny wrinkle drawing me into flight,

So I yearned for Leila,

but she was eyeing me the way the Lenni-Lenape

must have eyed those who came ashore with

helmets and horses, even though

I was half-Indian, myself.

Ronaldo

(Previously published in armarólla.)

Often, we met at Mr. Ali Beheshti’s

for a ride to his laundry, where Hamoudi and I worked,

so far only in winter months, when the heat from the dryers

was tempered by Mediterranean breezes, alhamdulillah,

praise God, as the Muslims had taught me to say

in the event of anything short of haram, or God forbid,

which the laundry was almost,

now that March had begun prickling us

with the gentlest–alhamdulillah–hints of summer.

Mr. Beheshti’s home had bright marble tables,

chairs carved from imported wood,

and ochre carpets from Iran.

In one corner was a little shrine

to his brother-in-law-in-the-Resistance,

as Lebanese call it:

three shelves of dog tags, ribbons, medals,

gazelle and horse figurines,

inlaid boxes, a golden sword embossed

with curlicues of Arabic calligraphy,

and photos of bearded imams,

one with the brother-in-law-in-the Resistance,

who held a Hezbollah flag:

summer yellow with AK-47, green, on high.

Mr. Beheshti’s clamshell sounded an electronic Baladi:

doom-doom—TAK-doom—TAK!

“Alhamdulillah,” I heard,

a short cut for “I’m fine.”

Later, Mr. Beheshti gave us the play-by-play

for the call, which was from

the brother-in-law-in-the-Resistance,

who wanted to discuss fútbol,

the match between Russia and Brazil,

and everyone’s hero, Ronaldo, the great Brazilian striker.

It was a friendly match;

the big battle would come

in the World Cup this summer, so the important thing,

was that no one get injured, insha’Allah.

The cold was in Russia’s favor,

but, fifteen minutes into the match,

Brazil’s captain Roberto Carlos crossed the Russian line

fifty meters from the goal, prepared to pass

to Ronado, who was waiting behind a four-man bulwark,

but Carlos, faking it, tapped the ball two steps ahead

and—surprise!—booted straight through

for a goooooooooooalhamdulillah!

but not before Ronaldo threw out his arm,

and almost committed haram

when the ball hit him on the way.

W-Allah! The path is narrow, Ali.

One-zero to the end, Brazil played hard defense with substitutes,

because the important thing

was that none should fall

before the big battle to come.

The sun rose twice on the cooling sea,

its gleams and shadows crossfading with the hours

through shine, shadow, red ochre, and night,

but—haram—the brother-in-law-in-the-Resistance

would not be around

for the big battle to come.