As the community slowly emerges from our Coronavirus cloisters, we eagerly anticipate the opportunity to reconnect with family, friends, travel and social life. I am also personally attempting to do an inventory of my time spent disconnected and locked-down. Truth be told, it was mostly boring. Holed-up and following a humdrum routine with very little chance to get a change in scenery. It’s already cliché to mention that the Zoom session went from useful novelty to bane of existence.

There were bright spots, however. I was able to tackle many books I’ve been wanting to read, but never could commit consistently to the time required. The book from which I learned the most this past year was a Christmas gift from a close friend of ours. While get-togethers and holidays were all more or less canceled, some small tokens could always be dropped off in the style of DoorDash or Amazon Prime. And so this winter I read Adam Hochschild’s 1998 best-seller “King Leopold’s Ghost,” the history of Belgian colonization, conquest and terror in Central Africa.

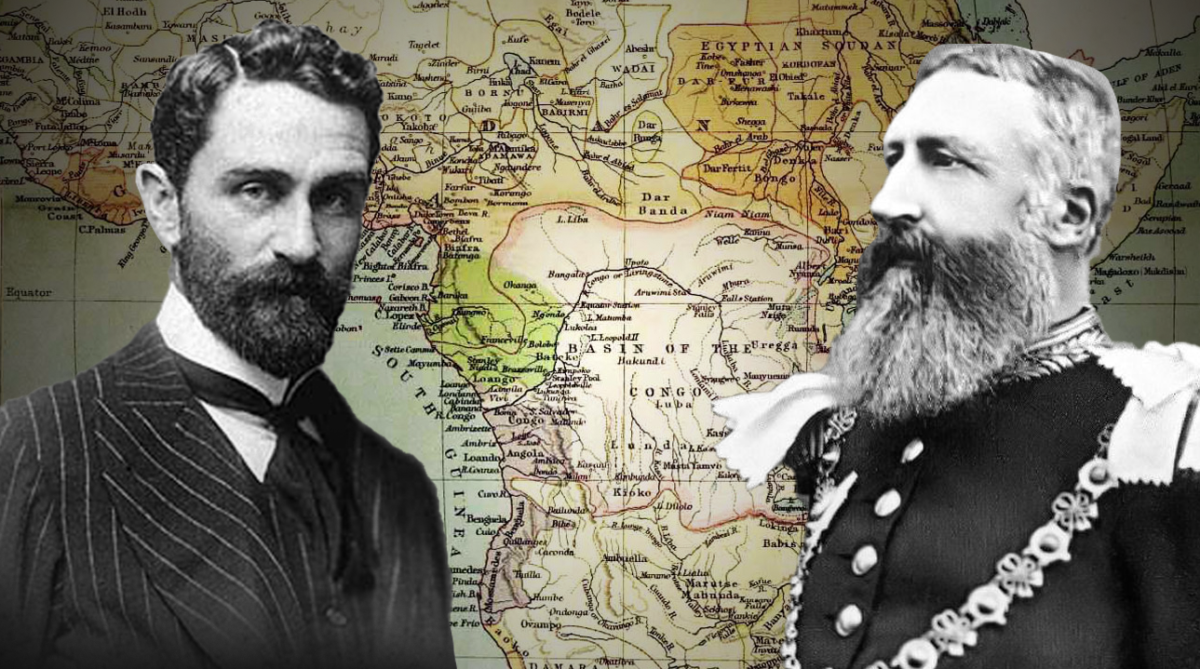

Some may know parts of the story, from Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão to H.M. Stanley and “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” to the classic 1899 Joseph Conrad novella “Heart of Darkness.” But there’s a part of the narrative that is less well known. The book’s subtitle gives a hint – A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Who possessed the idealized courage to champion the cause for the unseen and enslaved? What background and circumstances produced such a noble individual? Who is our hero?

Roger Casement was an Irishman, who, in 1883, aged 19 years, made his first voyage to the Congo. Casement had worked alongside Stanley, but the two’s disposition to their work was at extreme opposites. Stanley was, to put it both bluntly and truthfully, a violent, sadistic egomaniac. Casement worked on contract with European shipping interests as a surveyor and as a purser, or a ship’s bookkeeper. But his techniques were not in line with his abusive colleagues. One employer remarked that Casement, “is very good to the natives, too good, too generous, too ready to give away. He would never make money as a trader.”

Casement also stood out as a fine physical specimen with a generally pleasant demeanor. The Irish writer Stephen Gwynn noted that, “he seemed to me one of the finest looking creatures I had ever seen, and his countenance had charm and distinction and a high chivalry. Knight errant he was.”

Joseph Conrad met Casement in the Congo in a place called Matadi, as evidenced by a diary entry of Conrad’s from 1890:

Made the acquaintance of Mr. Roger Casement, which I should consider a great pleasure under any circumstances… Thinks, speaks well, most intelligent and very sympathetic.

For most of the 1890s, Casement worked for the British colonial administration, but he soon was moved to protest publicly against the horrors he witnessed. In 1894 he was called to a private meeting with King Leopold. The King defended the atrocities as uncommon, infrequent and the work of some men whose character deteriorated in the African climate.

Around this time, a man named E.D. Morel was working for the large shipping interest Elder Dempster out of Liverpool. Morel was a middle manager who once or twice monthly would travel to Antwerp and Brussels to log inventories, review ship statuses, and make the necessary reports. What Morel saw disturbed him greatly. While vast loads of valuable raw rubber were coming into Europe, the only goods going out were guns, chains and shackles.

Morel’s documentation and testimony prompted allies in the British Parliament to pass the Congo protest resolution. This resolution ordered the English Crown to investigate claims of slavery, gruesome torture––including the severing of hands and feet––and the display of hands and skulls as souvenirs, among other atrocities. These orders were sent by telegram to the British consul in the Congo for further investigation. The recipient of the message was Roger Casement.

Casement could have planned his investigation along the open rail line or the river, keeping close to accommodations and comforts. He did not. For over three months he went into the interior, sometimes hitching rides with American missionaries. There he was able to observe the rubber harvest firsthand. He also witnessed people’s families taken hostage until certain harvest quotas were obtained. He was able to count specific numbers of beating victims and inspect their wounds. He wrote to Belgian state officials not only criticizing the vicious methods, but also the system itself. This was included in just such a message to the Belgian Governor General of the Congo:

That system is wrong––hopelessly and entirely wrong… Instead of lifting up the native populations submitted to and suffering from it, it can, if persisted in, lead only to their final extinction and the universal condemnation of civilized mankind.

Casement’s notes during this time are stomach-churning. But it is this documentation that became the basis for the first global movement for emancipation and decolonization. Casement described his investigation as having, “broken into the thieves’ kitchen.” The farce of King Leopold’s “Free State” was exposed.

Casement and Morel took up this cause with great fire and determination. They became friends and began to publish investigative journalism on the colonial terror based on Casement’s evidence. A massive lobbying effort was undertaken. Individuals in the U.S., like Col. H.I. Kowalsky, took up the cause, advocating for American government action and raising funds for continued activism.

Morel published several books exposing the horrors of forced labor, kidnapping, violence, and murder and advocating for international sanction, most famously “King Leopold’s Rule in Africa” and “Red Rubber – The story of the rubber slave trade that flourished in Congo in the year of grace 1906.” In 1908, under increasing international diplomatic pressure the King of the Belgians, Leopold II, who had held the Congo solely as a personal monarchical asset, stealing its wealth and resources only for himself by terror and violence, relinquished it to the democratically elected Parliament of Belgium.

Still not a great result for the peoples of the Congo. Morel continued his work with the Congo Reform Association, the umbrella organization under which the advocacy operated until some modest reforms were implemented. Morel reported in early 1913 that, “revenues were no longer supplied by forced or slave labor. The rubber tax is gone. The native is free to gather the produce of his soil.” The organization held its final meeting in London on June 16, 1913.

Morel did have many racial views that would disgust the modern sentiment, as did most Europeans (and Americans) of that epoch. This should not be ignored or dismissed out of hand. But Morel did remain active in political life. As a pacifist, he was imprisoned for his opposition to the Great War. In 1922, he won a seat in the British Parliament replacing Winston Churchill, whom he greatly despised. Shortly after retaining his seat in the 1924 elections, Morel died of a heart attack.

Of all the activists and writers and diplomats in the world who comprised this first international human rights campaign, the real hero for me is Roger Casement. For all the work he had done, he had to earn a living. And so he accepted assignments in Brazil and Mozambique as British consul. But the work was lonely and unsatisfying. An indication of a new life’s focus was expressed in a letter to his friend Alice Green in the Spring of 1907. Casement wrote: “In those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold, I found also myself, the incorrigible Irishman.”

Casement began to support Irish independence and, to Morel’s concern, considered leaving the British foreign service and potentially forfeiting his pension rights. He wrote to Morel:

I have no use for your British government… You are one of the few who do not realise the national characteristics––and it is for this that I love you. When I think what J.B. [John Bull a.k.a. England] has done to Ireland I literally weep to think I must still serve – instead of fight… I do not agree with you that England and America are the two great humanitarian powers… [They are] materialistic first and humanitarian only a century after.

Casement did go on one more official investigative mission. He uncovered similar brutality meted out against Amazonian Putumayo natives in South America. While sometimes reinforcing the misguided Noble Savage trope, Casement once again went above and beyond. Not only by documenting the atrocities and filing reports, but also in writing at length to influential elites on the Putumayo issue, including lobbying members of Parliament.

He was so successful he was awarded a knighthood, for which the idea of accepting brought him much agony (considering his Irish republican views). He ultimately accepted, but when it came time to kneel before His Majesty, he called in sick.

Sir Roger Casement retired from the consular service in 1913 and immediately began to work for a free Ireland. As World War I began, he was attempting to raise money from Irish-Americans in the U.S. sympathetic to the cause. Then he pushed further. Shaving his beard and obtaining a fake passport, he traveled to Germany to attempt to persuade the Germans, if they were to win the war, to train the captured Irish soldiers as a nationalist brigade. He even suggested that Egyptians, another population suffering under a European colonial boot, could fight alongside.

The Germans were suspicious of Casement’s anticolonialism and snuck him back to the coast of Ireland in a submarine. On April 21, 1916 Casement was set off in a small boat with two other comrades just off the west coast of Ireland. He was hoping to join other freedom fighters underground and continue the struggle. Shortly after hiding a cache of guns, ammunition and maps on the beach, Casement was arrested and charged with high treason.

On August 3, 1916, Casement was led to the scaffold at London’s Pentonville Prison and hanged. The hangman called him “the bravest man it fell to my unhappy lot to execute.”

The story of Roger Casement taught me a great deal. Lessons about the effectiveness of organizing and advocacy journalism. How activism can be fulfilling and effective if the motivation is genuine and the commitment is sustained for the long haul. And how to confront the agony of being financially tied to capitalistic mechanisms of evil and understanding that Capital is the true impetus of colony, slavery (both the chattel and wage varieties) and systemic oppression. Accepting having made a living off it, but finding the courage to fight it anyway. And never backing down from injustice, inequality, oppression or occupation anywhere.

One last detail adds context, poignancy, and irony to the story of Casement and his role in the first international human rights campaign. Throughout his life of fighting against violent oppression of human beings, Casement himself was not entirely free. Roger Casement was a closeted gay man. And while he knew this fact could never be made public, he still made vague references to his sexuality in his writings. For example, these few lines of verse, not published until after his death:

I sought by love alone to go

Where God had writ an awful no

…

I only know I cannot die

And leave this love God made, not I

So to all my LGBTQIA friends and comrades, very Happy Pride month. Let’s keep up the fight side-by-side.