Before the assassination at the Lorraine Motel, before the curfews and soldiers with fixed bayonets patrolling the streets of Black neighborhoods — before the riots — someone hurled a firebomb into Almar Liquors on the 1200 block of North Heald Street and set the building ablaze. When police and fire crews arrived at the scene, flames had engulfed the walls and ceiling of the first floor.

About two hours later there were reports of another fire less than a mile away at Jack’s Market on East 28th Street. Just a few minutes after that, yet another- this time at Eddie’s Market on the corner of 22nd and Spruce. Meanwhile, calls were coming into police headquarters of bricks hurled through business windows and pedestrians pelted with stones by passing cars.

There were 159 riots during the Long Hot Summer of 1967. Dozens had been killed in Newark, New Jersey. 8,000 National Guard troops were on the streets of Detroit in a desperate attempt to bring calm. The death toll was rising daily, and news reports from Detroit of rooftop snipers and tanks firing on city buildings were prominently displayed on the front pages of Wilmington’s two daily newspapers.

Every day the riots grew closer, spreading to Toledo and Rochester, and then to Cambridge, Maryland, where the National Guard was also deployed. Now, in the early morning of Thursday, July 27, 1967, some feared that Wilmington may be next.

Governor Charles L. Terry took a hard line. According to Terry and those in his administration, riots were spontaneous outbursts of violence orchestrated by criminal opportunists. From the perspective of law enforcement, any act of civil disturbance was akin to arsonists throwing a match on gasoline. The objective for law enforcement is containment: to keep the initial fire from spreading to other areas; to find the arsonists before they can strike again; and lastly, to deploy an overwhelming show of force to keep the peace and deter copycats.

A Southern-style Democrat and former Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, Terry deeply believed that hard-line, punitive law enforcement acted as a psychological deterrent to criminal behavior. While campaigning for governor in 1964, Terry was asked during an interview if he supported legislation to repeal Delaware’s infamous whipping laws. The laws were still on the books, but the old whipping post in Dover hadn’t been used in years. The issue had only re-entered public dialogue because, on November 13, 1962, Superior Court Judge Stewart Lynch ordered Franklin W. Cannon Jr. — a poor white man — to be “lashed 20 times on a charge of having violated his parole.” 1

Cannon’s sentence was eventually commuted; nevertheless, the debate continued into the gubernatorial election.

“I think it’s a good thing to have,” Terry responded regarding the whipping post during a radio debate. “It’s there. It acts as a deterrent. I think it has acted as a deterrent. Our crime rate is very low.” 2

In the final year of his term, Terry’s hard-line approach to law and order would result in one of the most controversial decisions of any governor in modern Delaware history. In the aftermath of intense, but non-lethal rioting that consumed downtown Wilmington on April 9 and 10, 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Terry activated the entire Delaware National Guard — 2,800 soldiers — to patrol the streets of “The Valley,” a predominantly Black and poor neighborhood just west of downtown. Against the wishes of Wilmington mayor John Babiarz and much of the City Council, Terry kept the National Guard in Wilmington for nine months, the longest peacetime occupation of an American city since the Civil War. Even after Terry narrowly lost reelection to Russell W. Peterson in November 1968, he steadfastly refused to remove the National Guard. Peterson ordered the National Guard out of the city on his first day in office, January 21, 1969.

The 1968 riots and subsequent National Guard occupation of Wilmington are remembered in infamy. On the 50th anniversary of the riots and occupation, cultural institutions revisited this stain on our heritage to reflect on the political currents that drove Delaware toward violence and authoritarianism.

How did Delaware get to the breaking point?

To better understand the origins of the 1968 riots and National Guard occupation, we must examine racial and social divisions that preoccupied Delaware. Also, how events during the Long Hot Summer of 1967 were exploited by Terry to stir fear among white residents and engineer a legislative coup of Wilmington’s local governance.

“Let’s face it, the city is decaying”

City leaders had long promised Wilmington’s impoverished Black communities that help was on the way. But when urban renewal came to Delaware in the 1950s and 1960s, it only exacerbated simmering racial tensions.

Throughout the 1950s, hundreds of Black families were displaced from slums across Wilmington’s east side to make way for the Poplar Street Redevelopment Project. City officials had intended for the displaced to relocate to housing projects in northeast Wilmington, and some did. However, many more relocated to West Center City — a densely populated neighborhood just a few blocks west of downtown — where large, historic row homes were purchased by slum landlords and renovated into apartments. As more Black residents moved into West Center City, white residents sold their homes for a loss and fled to the suburbs, which allowed even more slum landlords to renovate even more single-family homes into apartments. 3

As homeownership plunged and poverty increased, the fabric of the community began to fray. 4

When the outgoing city council approved the I-95 right-of-way through the core of Wilmington’s west side in 1957, once-stable communities fell even further into disarray. To make way for the interstate, 350 homes were to be demolished. But when most of those homes were purchased in 1958, plans for the highway had not yet been finalized and the homes sat vacant for over a year, attracting crime, arsonists, and rodents the size of small cats. 5

Another round of urban renewal in 1963 brought even more broken promises. The West Center City Urban Renewal Project promised to bring $20 million in investment to renovate 800 existing homes and build 400 new homes. But just as the Wilmington Housing Authority began demolition, the project’s funding was pulled. 6 By 1967, much of West Center City had fallen into neglect.

“Let’s face it, the city is decaying,” wrote local columnist Richard Sanger. “The thing they call blight is spreading like dry rot in west side residential neighborhoods. We are creating new slums just as fast as we knock down the old ones — probably faster.” 7

Living was hard. Unemployment was high, rents astronomical and living conditions abysmal. Historian Carol E. Hoffecker paints a very bleak picture of day-to-day life in Wilmington’s densely populated urban Black neighborhoods:

Dependent mothers who got only $170 a month in welfare payments had to pay $100 of that money just for housing and utilities. Housing codes were not being enforced, while slum landlords flourished. Unions and employers conspired to keep blacks from getting jobs, the schools were poor, and there were inadequate services for working mothers. 8

Under these conditions, crime increased. The area of West Center City between Washington and Adams is known as “The Valley” had become the most violent in the city. 9

Moreover, Wilmington’s Black youth were increasingly at odds against a police force they viewed as an instrument of systemic oppression.

“This is deep-seated resentment” against the police, said state Sen. Herman M. Holloway Sr. of Wilmington. “They feel that when they haven’t been brutalized, they’ve been spoken to as if they were common dogs.” 10

Some began to fear that systemic oppression would lead to violent blowback, as it had in cities across the nation that summer. In June 1967, following a four-hour meeting on race relations in Wilmington, U.S. Attorney Alexander Greenfield released a shocking statement explaining the dire situation:

The causes of unrest are poor housing, discrimination in employment, and social rejection, but the focal point of all anger is relationships with the police. While all had the highest praise for the police commissioner and chief, all speakers told several stories of alleged discriminatory and provocative acts by police on the beat. The police were described as lacking in respect for the Negro in failing to treat him as a human being, and as being extraordinarily prejudiced. All the participants alleged that riot squad tactics by police would eventually provoke a riot. 11

Over the coming weeks, rumors swirled that a riot was imminent. Gov. Charles L. Terry Jr. went so far as to publicly denounce rumors of an impending riot.

“Rumors can only inflame the mind, can build a dangerous situation to create the very thing we’re trying to avoid,” he said. Wilmington Mayor John E. Babiarz agreed, saying the riot rumors had “no basis in fact.” 12

“Knocking out windows”

The tense calm that had prevailed in Wilmington was finally shattered during the final weekend of July 1967 as simmering racial tensions escalated into street violence. 13

On Thursday night, several cars pulled up to a tavern in Little Italy that was known to refuse service to Black customers. Dozens of Black teenagers rushed inside, “knocking out windows and breaking liquor bottles, other glassware, tables, and chairs,” police told the Evening Journal. 14

Violence escalated sharply the following night after “a maroon and white car” pulled up alongside the open door of a private social club in Little Italy and fired multiple gunshot rounds inside, wounding four. 15

An angry white mob gathered on Lincoln Street and threatened violence to a nearby Black neighborhood. Police arrived in riot gear, armed with shotguns, and told the crowd to disperse. They refused until two Catholic priests appealed for calm. 16

“We don’t need any posses or vigilantes,” Mayor Babiarz said in a statement the following day. “The best any citizen can do is to try to keep some of these young people off the street when it gets late.” 17

Reports of gunfire continued through the early morning hours of Saturday, July 28, in West Center City, where three were wounded in drive-by shootings. There were at least three more reports of shotgun fire but no further victims. The identities of the shooters were never discovered.

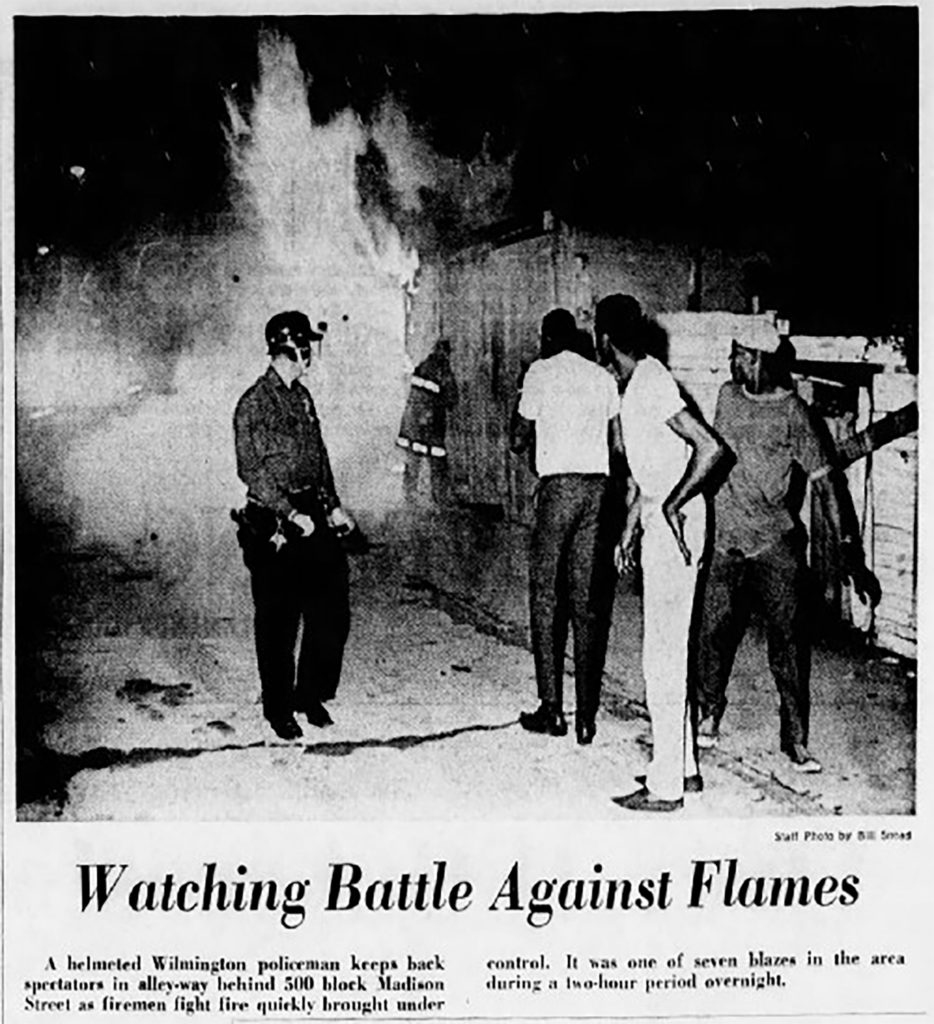

In total, seven were admitted to area hospitals, all with non-life-threatening injuries. Just as the rash of shootings was coming to an end, at about 1:00 a.m. Saturday morning, vacant homes across West Center City were set ablaze, as were cars and trash cans. None of the fires burned out of control, and all were contained relatively quickly.

One fire crew responding to a fire on Jefferson Street was “pelted with bricks.” Meanwhile, a crowd of young people marched up Madison Street, smashing windows and breaking into white-owned corner stores. 18

As the night unfolded, Mayor Babiarz feared a riot. He contacted Terry at 1:30 a.m. to request assistance from the Delaware State Police. Thirty minutes later Babiarz ordered a curfew, which went into effect at 2:30 a.m.

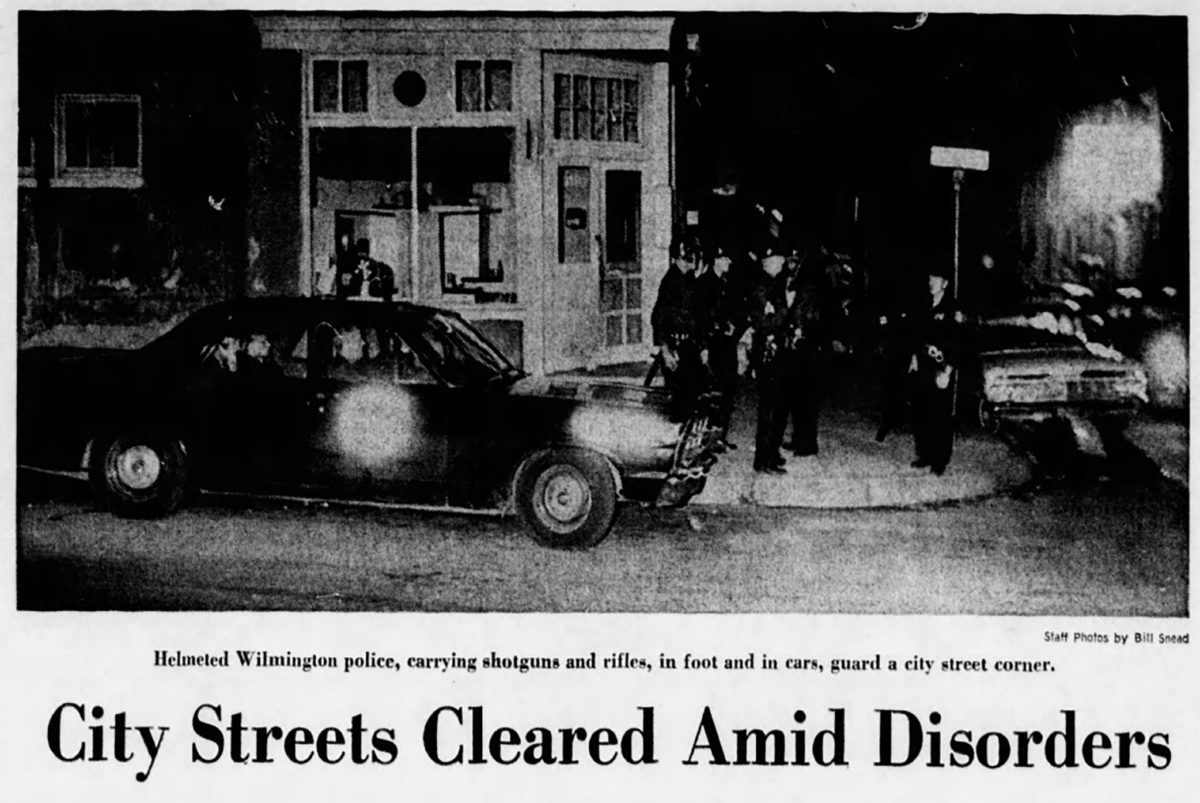

In response, Terry activated 1,500 National Guard troops and ordered the Delaware State Police to patrol Market Street in riot gear. Armed with rifles and shotguns, helmeted police descended on “The Valley” and began rounding up looters at ransacked corner stores.

“Over 100 Arrested In Disorders Here” proclaimed the front page of the Evening Journal. 19

By 3:30 a.m. on Saturday, July 29, all was quiet across Wilmington. Gunfire had ceased. Fires were extinguished. Looters were either arrested or returned home. There were no deaths. Police never fired a shot.

Out of an abundance of caution, Babiarz reinstated the curfew on Monday, July 31; however, the city had calmed down.

“I think people are snapping out of it now,” he said. 20

“Common Sense Prevails” declared an editorial in the Evening Journal. “It may be that the rain of Saturday night was responsible for cooling off a potentially violent weekend in Wilmington, but we’d prefer to attribute the rapid return to normalcy to the uncommon good sense of the citizens of the community.” 21

The Crackdown

Over the coming weeks and months, racial divisions that had long been eating away at the social fabric of Delaware came to the forefront of a statewide public conversation.

Wilmington’s Black political leaders and community activists called on Terry to address the root causes of unrest: poverty, blight, and the systemic oppression that was exacerbating racial tensions between Black communities and the predominantly white police force.

“The Negroes in this state have been held in contempt by you, and their plan for programs to alleviate root problems in the ghetto have been met with silence,” said Littleton P. Mitchell, president of the Delaware NAACP.

“Visit the ghetto areas of our state and converse with those who are forced to remain there. Listen to their complaints and their suggestions for solutions to problems; see the squalor that surrounds them.” 22

Among some government officials, Wilmington’s business community, and many white residents, however, the specter of a burned-out Detroit loomed large in the imagination, and many feared that the civil unrest that took place in July 1967 was merely a precursor to something much worse.

“Wherever I go in Delaware, I find there is deep concern about the violence and lawlessness that have rocked some of our major cities,” Terry said one week after the disorders. “The tragic destruction of life and property that has occurred in other parts of the United States must not be duplicated in Delaware.” 23

Under pressure to understand the factors fomenting unrest, Terry appointed the Investigative Committee on Cause of Civil Unrest and called for a comprehensive report. The commission spent the next two months investigating the disorders. When the report was released on October 6, the conclusions were damning. The Subcommittee on Grants and Low-Cost Housing, chaired by Harris B. McDowell Jr., issued the following warnings:

The committee is convinced beyond question, and this is confirmed by unanimous testimony, that the fact that thousands of Delaware families are compelled to live in houses which are unhealthy, unsafe, and demoralizing to dignity was indeed a major factor and continued to be in fomenting demonstrations and civil unrest. The committee is of the firm belief that failure now to act on this problem of slum and substandard housing and the lack of adequate housing for lower and medium-income families is a threat to the basic economic fabric of our state and endangers the safety and security of every citizen, no matter where they live in Delaware… The committee also finds that discriminatory practices are a basic cause of unrest. Those practices — particularly in housing — contribute directly to the feelings of frustration and rage which ultimately break into the open in violence. They also contribute indirectly to unrest by causing law-abiding citizens to condone riots instead of helping to prevent and to quell them.24

Reports by subcommittees on Employment, Recreation, and Auxiliary Services came to a similar conclusion, with the latter reporting on poor housing: “This is so obvious, nothing further has to be said.” 25

In short, the commission called for compassion on the part of Delaware’s lawmakers.

At the same time, Terry proposed legislation that would define his campaign for reelection the following year: any disorders were to be treated as a revolt and responded to with an immense show of force. On Friday, August 4, Terry addressed a joint session of the General Assembly and made clear that he found compassion to be a weakness.

“We’re not dealing with ordinary times,” he said. “We’re dealing with a rebellion. When insurrection is with us, we can’t coddle anybody.” 26

Terry called on the General Assembly to convene an emergency session to pass “riot laws” that would expand the governor’s authority to declare a state of emergency and impose curfews during times of crisis, “either statewide or in specific areas of the state,” such as downtown Wilmington. 27

Terry also asked for a “mandatory three-year jail term,” without parole, “for anyone convicted of willful, wanton destruction of property.” 28

Attorney General David P. Buckson quickly backed Terry’s proposals, as did leaders from both parties in the General Assembly, all despite opposition from civil rights groups. “If the ACLU opposes it,” said Buckson, “it must be a good law.” 29

Parliamentary rules were suspended to speed up the debate, and within hours lawmakers voted unanimously to approve the riot laws. 30

State Sen. Louise Conner offered an amendment that would have allowed parole for persons convicted of these offenses, but she found little support.

“I don’t want to be soft,” she said, “but this is a bad provision that could apply to a rumble at Mount Pleasant [High School].” 31

Speaking off-the-record, several legislators expressed deep concerns about the severity of the proposed riot laws, but few disputed the laws publicly. In an interview with Larry K. Martin, the Dover Bureau Chief for the News Journal, a “leading Republican” said he “hated like the devil to pass those laws. They weren’t right.” Another legislator remarked, “In the whole time I’ve been in the General Assembly I haven’t had a day that bothered me like that one.” 32

The riot laws were on the governor’s desk just seven hours after being introduced in the General Assembly. Immediately upon signing, Terry declared a state of emergency in Wilmington, despite no further outbreaks of violence.

“Rioting and looting constitute criminal behavior that cannot be tolerated,” he said. Adding that such actions were necessary “to forestall criminal disorder before it has an opportunity to get started.” 33

Terry kept Wilmington under a state of emergency for weeks, claiming without any evidence there were “forces at work to keep alive the spirit of dissension and lawlessness that marks a riot and to perpetrate worse mischief if the opportunity presents itself,” all according to “many reliable sources,” which he never disclosed. 34

Under the new state of emergency, dozens were arrested for mostly minor offenses. Mayor Babiarz claimed the arrests “resulted from intense police enforcement of the new laws, not from any significant degree of disorder.” Four men in a bar fight were arrested under the riot laws and immediately faced the mandatory three-year minimum sentence.

Wilmington City Councilman Wade U. Hampton called on the General Assembly to amend the riot laws: “I am sure other people would like to contribute to making laws that are not aimed at just the Negro or any other minority group.” 35

Lawmakers refused.

Through these actions, Terry drew a line in the sand: on the one side was law and order; on the other, anarchy.

The General Assembly also resumed work on revising Delaware’s criminal code. “Code Widens Arrest Powers” reported William P. Frank. “A section of the proposed code would give greater authority to police officers to use force to make an arrest, even if the arrest seems to be unlawful.” 36

Terry lifted the state of emergency in Wilmington on September 6, 1967. Despite fierce opposition from civil rights groups, Terry maintained that the riot laws were “a useful and powerful deterrent to those who are not respecters of the lives and property of others.” 37

In remarks delivered to the Southern Governor’s Conference the following week, Terry doubled down on his hard-line stance on the psychological deterrence of overwhelming force. “Don’t let anyone think the presence of the state police with riot gear is not a deterring factor.” 38

Terry set the tone, and others in his administration followed. One week before the Investigative Committee on Cause of Civil Unrest issued its final report, the Terry loyalist who headed the commission, Joseph Bradshaw, sent the governor a summary memo of the report without approval from the other members of the commission, drawing conclusions that directly contradicted the findings of the report.

On the root causes of civil unrest, Bradshaw declared that poor housing and unemployment played only a minor role compared to the “feeling of exhilaration” and “carnival or fiesta atmosphere” of mob mentality. On blight in West Center City, Bradshaw blamed residents, stating, “there is an educational need also for individuals to take care of their own homes,” even though most residents in the affected areas were renters.

As for the lack of progress in regards to addressing poverty and blight, Bradshaw deflected blame. “It is impossible for us to communicate with the Negro leaders,” he said. And in response to the accusation that Black communities were not treated with dignity, Bradshaw casts the blame back on those same communities. “In order to be treated with dignity, it becomes imperative that you treat others also in a dignified manner.” 39

Bradshaw’s actions seriously undermined the credibility of the Committee’s report. During its final meeting, all members of the committee rejected Bradshaw’s conclusions. 40

The disturbances that took place in July 1967, they said, were the inevitable outcome of decades of racism, segregation and discrimination against Wilmington’s Black communities; of pent-up outrage against systemic oppression designed to lock entire generations of Americans into a lifetime of poverty; of living in slums, denied the promise of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.

In the months following the unrest, the city and state did little to help those in need. In an attempt to address high unemployment in Black neighborhoods, job centers were quickly opened in West Center City and the East Side, attracting hundreds of applicants. 41

The job centers were closed down only five months later. 42

As autumn turned to winter and winter into spring, an uneasy calm prevailed in Wilmington. Terry promised to have the National Guard on standby throughout the summer. 43

And then, on April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated as he stood on a balcony at the Lorraine Motel. Congregations across Wilmington gathered to pray for peace, just as they’d done many times before. But there could be no peace. Not after this.

As night fell on Wilmington, and as fire-gutted buildings across downtown smoldered to ash heaps, Terry once again declared a state of emergency in Wilmington. Thousands of National Guard troops rolled into Wilmington and would not leave for nine months.

A revised version of this article originally appeared in Wilmington 1968: A Sourcebook, edited by Simone Austin and published by the Delaware Art Museum.

Notes

- William P. Frank, “Officials Argue Over Cannon Case,”Evening Journal (September 16, 1964).

- “Terry Says He Favors Lash Law,” Evening Journal (September 14, 1964).

- Carol E. Hoffecker, Corporate Capital: Wilmington in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983), 159–164.

- Margie Fishman and Jenna Pizzi, “Decades of revitalization plans haven’t diminished violence,” The News Journal (December 11, 2015).

- “Rats Create Gray Terror Along Route of Freeway” The Morning News (May 18, 1961).

- Margie Fishman and Jenna Pizzi, “Decades of revitalization plans haven’t diminished violence,” The News Journal (December 11, 2015).

- Richard Sanger, “A Wake-Up or a Wake?” Journal-Every Evening (April 13, 1960).

- Carol E. Hoffecker, Corporate Capital: Wilmington in the Twentieth Century(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983), 188–90.

- Hoffecker, Corporate Capital, 183–84.

- “Grievances To Be Listed By Negroes,” Evening Journal (July 27, 1967).

- Tom Malone, “Wilmington called ripe for racial rift,”The Morning News (June 28, 1967).

- Tom Malone, “Riot rumors plague state,” The Morning News (July 27, 1967).

- “3 Fire Bombs Hurled at Stores Here,” Evening Journal (July 27, 1967)

- “Hit-Run Rowdies Rip Lincoln St. Bar,” Evening Journal (July 28, 1967).

- “Shotgun fire from car hits 3 in city club,” The Morning News (July 29, 1967).

- “100 Are Seized To Quench Riot In Wilmington,” The Philadelphia Inquirer(July 30, 1967).

- “City Enacts 3 New Emergency Laws,” Evening Journal (July 29, 1967).

- “City Streets Cleared Amid Disorders,” Evening Journal (July 29, 1967).

- “Over 100 Arrested In Disorders Here,” Evening Journal (July 29, 1967).

- “City Curfew Is Reinstated By Babiarz,” Evening Journal (July 31, 1967).

- “Common Sense Prevails,” Evening Journal (July 31, 1967).

- “NAACP asks Terry to act,” Morning News (August 1, 1967).

- Charles Terry, “Governor’s Message to Assembly,” Evening Journal (August 2, 1967).

- State of Delaware, Report of the Investigative Committee on Cause of Civil Unrest (October 6, 1967). Charles E. Terry Collection. Delaware State Archives.

- Ibid.

- Journal of the State Senate (1967), August 4, 1967, p. 248.

- Charles Terry, “Governor’s Message to Assembly,” Evening Journal (August 2, 1967).

- Charles Terry, “Governor’s Message to Assembly,” Evening Journal (August 2, 1967). 124th General Assembly, Chapter 116: An Act To Amend Title 11, Delaware Code, Relating To Crimes By Imposing Criminal Penalties For Riots. 124th General Assembly, Chapter 117: An Act To Amend Title 11, Delaware Code, Relating To Crimes, By Imposing Criminal Penalties For The Manufacture, Transfer, Use, Possession Or Transportation Of Molotov Cocktails Or Other Explosive Devices. 124th General Assembly, Chapter 118: An Act To Amend Part II, Title 20, Delaware Code, Relating To Civil Defense By Conferring On The Governor Additional Powers To Regulate And Restrict Activities Of Persons During A State Of Emergency Proclaimed By Him; And To Provide Criminal Penalties For Violation Of Emergency Directives Of The Governor Or For The Commission Of Other Acts During The State Of Emergency.

- Larry K. Martin, “Buckson Backs Terry Request For New Civil Disturbance Laws,” Evening Journal (August 3, 1967).

- Andreas George Schneider, “Delaware: The Politics of Urban Unrest, July 1967 — January, 1969.” Thesis for the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs

- Larry K. Martin, “Terry puts city under new law,” The Morning News (August 5, 1967).

- Larry K. Martin, “Legislators Not Unanimous on Riot Acts,” Evening Journal (August 10, 1967).

- Larry K. Martin, “Terry puts city under new law,” The Morning News (August 5, 1967).

- Charles Terry, “Text of Terry’s conference,” The Morning News (September 19, 1967).

- Wade U. Hampton, “Why Weren’t Jobs There Before Disorder?” Evening Journal (August 19, 1967).

- William P. Frank, “Code Widens Arrest Powers,” Evening Journal (August 7, 1967).

- Charles Terry, “Text of Terry’s conference,” The Morning News (September 19, 1967).

- “Trooper deterrent claimed by Terry,” The Morning News (September 14, 1967).

- Joseph A. Bradshaw, Memo to Governor Charles L. Terry (September 29, 1967). Charles E. Terry Collection. Delaware State Archives.

- “Pay-or-Burn Cases Reported: Poppiti,” Evening Journal(October 3, 1967).

- Ralph S. Moyed, “Job centers get 200 applicants,” The Morning News (August 15, 1967).

- “2 Job Centers Born in Unrest To Be Closed,” Evening Journal (December 28, 1967).

- “Terry Sees ’68 Unrest Widespread,” Evening Journal (January 23, 1968).