My earliest memory is of a chicken.

“Tell me the cookoolala story,” I would ask my dad, and he would tell me about a mean, aggressive, bully of a chicken who pecked everyone. Until one day, it pecked me. “If someone ever hits you, you hit them back,” my father often advised, and the moral of this strange tale was no different. It ended with a snapped neck and a poultry dinner at India’s finest hotel.

I believe that chicken brought my family to America. As a chief engineer in the merchant marines, my dad had sailed the world—Italy, Romania, Egypt, Japan. He could have earned a graduate degree anywhere on Earth, but it was the University of Delaware, with its cookoolala mascot, that brought us from India to the United States.

Technically, it was the graduate program in marine policy, but I like to think it was the mascot with a bandage on its beak. Fightin’ Dick, as he was known from the 1950s to mid-90s, was not some chicken to be cooked and eaten for dinner. Here, instead, was a symbol of resilience. Battered and bruised, the Blue Hen stood defiant, refusing to go down without a fight.

I was four years old when we arrived in America in 1988. The only cassette we owned, Simon and Garfunkel’s Concert in Central Park, quickly became the soundtrack of my childhood.

I strolled around the grounds of Newark, feeling very much at home. I walked past Robinson Hall, wondering if the building was named for a woman whom Jesus loved more than she would know [and which was, in fact, named for Winifred Robinson, who helped open the University’s doors to (White) women in 1914. On road trips, I sang an American tune, counted cars on the New Jersey Turnpike, and hummed along to my father’s favorite song.

In the aftermath of 9/11, as America lay heartbroken, battered, and bruised, Paul Simon opened Saturday Night Live with that very song.

In the clearing stands a boxer and a fighter by his trade, and he carries the reminders of every glove that laid him down, and cut him, ’til he cried out, in his anger and his shame, “I am leaving, I am leaving,” but the fighter still remains.

Before the global pandemic, before the economic collapse, before the cries for racial justice, I found myself in a funk.

“How about Joe?” a colleague said to me shortly after the Super Tuesday primaries, and I scoffed. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” I replied. “The most diverse pool of presidential candidates in history, and we get another old White guy.”

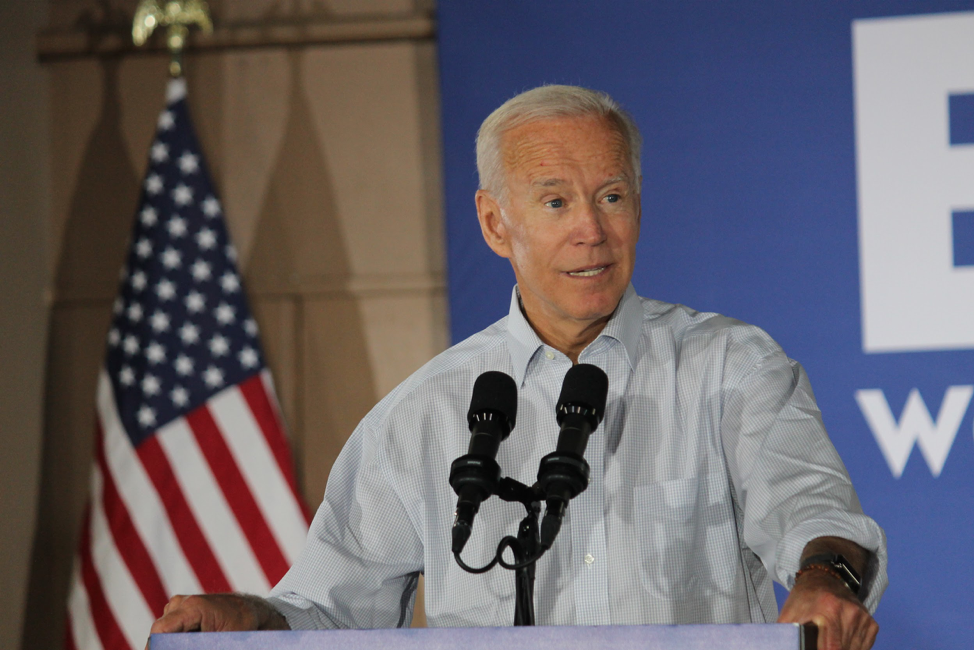

It was only later, amidst 2020’s grim onslaught, that I began to understand Biden’s power. That in this year of profound loss—loss of life, 200,000 Americans dead from an airborne virus; loss of liberty and justice, an innocent woman murdered in her sleep while her killers walk free; loss of normalcy; loss of happiness; loss of democracy; loss of kindness; loss of the very core of our identity, “one nation, under God, indivisible”—Joe Biden is the boxer. He has emerged from the depths of human misery beaten, but not broken; damaged, but not defeated. In the fight for the soul of America, he is the bandage on our beak.

And he’s not the fighter many of us wanted. He hails from the corporate capital of the world, befriends Republicans, and believes in compromise. It’s the Delaware Way. It’s what makes our state the First State. Where politicians bury a literal hatchet after elections and where differences are resolved peacefully because we live beside each other, under God, indivisible.

I have never met Joe Biden, but I wish he were sipping cocktails beside a pool right now. He should be in his basement, “Sleepy Joe,” listening to old records.

Instead, he cries out, in his anger and his shame, “Is this the America you want? Is anyone happy on this path? Can you handle another four months like this? Another four years?”

I am leaving, I am leaving, he told us in 2016.

But then the world collapsed, and the fighter still remains.